Dear Editor,

I have been gladdened by the recent debate caused by my article on the Necessity of the Art Deco Revival. If it has proven anything, it is that there are still men and women out there who care enough about art that they wish to write letters to online magazines and furiously debate it on social media. This is all to the good, for we are sorely in need of it. What so disappointed me about my own art college education was the sallow over-agreeableness of our seminars and lectures. People were devilishly careful not to offend each other. I’m very glad we have banished that reticence from our discussions!

I would first like to thank Paul Rhoads for his contributions to this debate and for my friend and colleague Fen de Villiers for his defence of Art Deco. Both are articulate and principled defenders of their position with a passion for art.

The following are various responses to Paul’s critiques.

1. The Character of Art Deco

It’s very difficult to define art historical styles or periods because in general there are no strict definitions. Much like national characteristics, it’s hard to put your finger on it. There is in fact a series of overlapping criteria that define Art Deco. There is no definition as such but family resemblances.

Paul characterises Art Deco chiefly as a style of decoration and design, and only secondarily as a style in painting, and then the painting is ‘merely post-impressionism’. According to Paul, Art Deco painting has no unique identity and is a derivative of this larger (and presumably more important) style.

On the latter point, it is no argument against Deco that it is connected to post-impressionism. All things have prior causes, and if Deco’s sole cause was post-impressionism that does not invalidate it. Paul would need to make an argument as to why it does so. In fact, I do not believe that Deco has a single cause or influence, but as Fen articulated in his response, it had many influences that shaped it. For sake of accuracy, I think it can be said that Cubism in particular is the form of post-impressionist painting that had the greatest influence on Art Deco, certainly the most striking. But again, this fact is no argument against the value of reviving Art Deco. We are simply shunting the question of value back to a prior cause. The question was regarding the value of Deco not its origins.

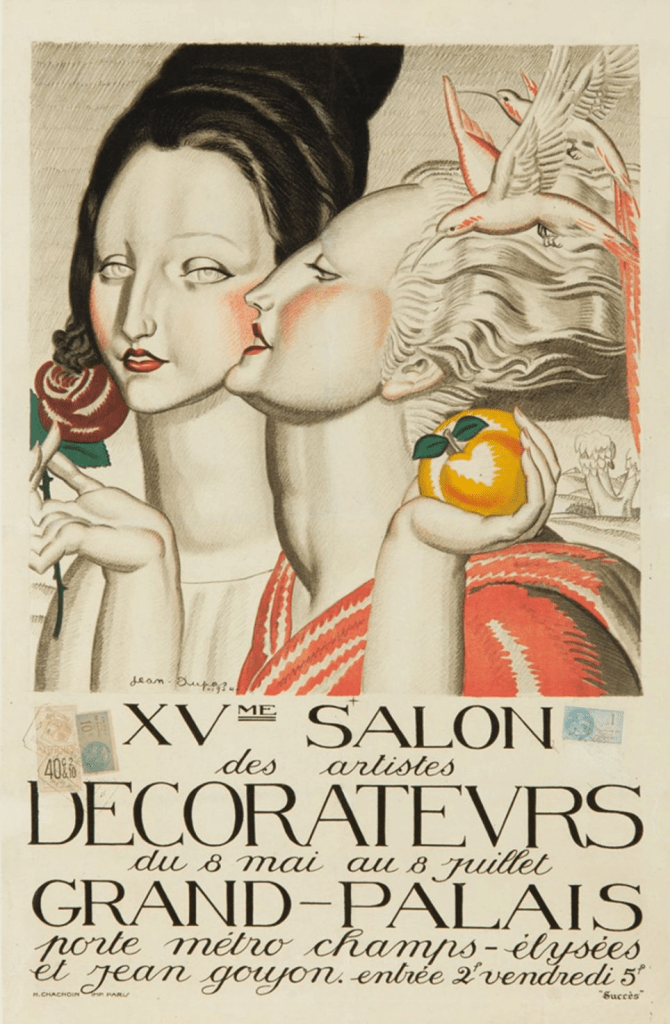

Art Deco painting does have its own identity, as Damien Chavez has pointed out. Painters like Dupas, Lempicka, Erté, Frampton, and Philpot can all be convincingly described as Art Deco painters. What is interesting here is that one can call these painters Deco alongside sculptors such as Chiparus and Picot, as well as designers like Ruhlmann and Lalique, and architects like William van Alen and Evan Owen Williams. There is general ‘Deco-ness’ to all of these practitioner’s work despite the fact they work in radically different art forms.

And this brings us to the former point made by Paul, that Deco is a style of design. This is more interesting and the crux of the issue. Indeed, Deco is a style of design but the scope of the concept is much larger in my mind than Paul’s. Deco was the last collective style to unite the plastic and applied arts in a total expression. This is why it is critical that we examine it, but more on this later.

2. The Modernist Condition & ‘Contemporarism’

However, Paul’s identification with post-impressionism is not entirely without merit. It is a characteristic of that tendency to value art’s role as creating form above art’s role of representing it. Cézanne said, ‘Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone. . .’ the emphasis being on the formal capabilities of painting.

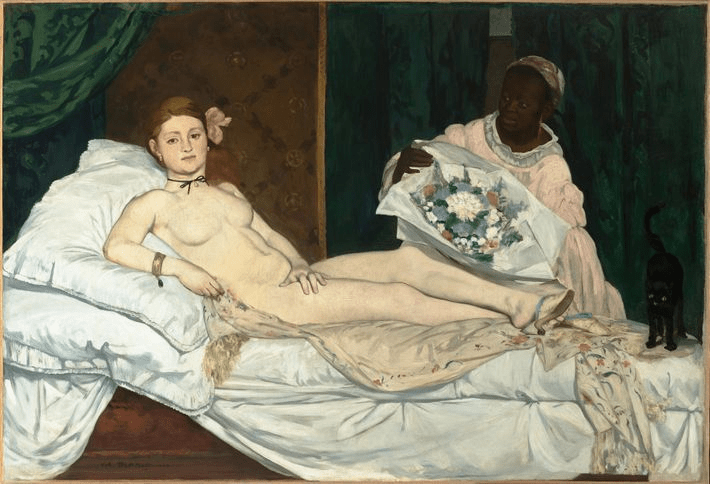

This is part of a larger characteristic of Modernism per se — the self-consciousness of art as art. Artists became aware of themselves as creators of form and representation and became aware of art as form. This was all contained within the pictures of Manet. When he made Olympia as flat as a playing card he highlighted the flatness of the picture-plane and the fact that the painting itself was an artifice as well as the representation of the nude itself (postmodernism in embryo).

It was from here that painting, drawing, and sculpture increasingly left the idea of representing the world behind in favour of abstraction, or later, in playing with self-referential icons. With it we lost a critical part of art’s purpose — to sincerely represent things to us. It became increasingly alienated from our world, dreams, and needs. Fine art truly became useless! And despite the calls from Abstract Expressionists like Rothko et al., abstract art is just less human than figurative art. Men and women have existential and spiritual needs that art is tasked to represent. Ultimately abstract art doesn’t fulfil these spiritual needs. Likewise this occurred in the world of applied arts and architecture. Functionalism replaced ornamentation, and with it our sense of making our world a meaningful part of us.

Art Deco is a style of design, the last to do so, to synthesise all the arts. Design here has a greater meaning than glass-making and silversmithing, but a broader conception of man bringing order and uniqueness to his world. Design is a vision, a representation, and the faculty to mould the world to represent that vision. It is the only method of expressing meaning in the plastic arts. Deco itself represents a means of doing this which unifies all our experiences and weds art to life. It represents a possibility that art in the modern world doesn’t have to be the desiccated husk of a former tradition but a living world of experience with a future.

In the 21st century we have enough historical perspective to evaluate the achievements of 20th century Modernism. No longer is there the tyranny of ‘Contemporarism’, to coin a neologism. Paul himself has outlined this impulse in his book Art in the Age of Anxiety, and characterises myself and Fen as stirring against it; in this Paul is correct. ‘Contemporarism’ was the insistence that art and artists follow lockstep with the zeitgeist and any deviation was labelled as irrelevant. Progress was absolute and there was no turning back. Of course, the nature and definition of that progress was always reliably malleable enough to suit the elite at the time.

Both Paul and Fen were personally hurt by this structure, although in Fen’s case it had ossified into ideological rather than artistic conformity. It has died simply because there is no more high culture left for it to piggyback on and from the fact that people finally started to see through it. The rise of the internet as well a populist revolt against cultural-political elites has led to a general questioning of modernity. It lives on of course but it is now truly a zombie. It holds nothing of promise. It has no future.

In this context then “larping” isn’t a very useful term. Within it is the same reductionist critique, the Manetian highlighting of artifice, that Modernism applied to art. But Man is artifice. He can choose to make the world around him represent himself and his values, or he can leave himself powerless to forces that will do it for him. There is no ‘larping’ or ‘non-larping’, there are only the resources and skills necessary to make something happen.

3. The Modernist Condition & ‘Contemporarism’

With the Contemporarist elites fading in their power there really are no more fig leaves to cover the civilisation of the unit I outlined in the original article. Without the lies of relevancy and progress all we are left with is Man-as-cipher. This was brilliantly foreseen in dystopian novels like Zamyatin’s We. Human beings are mere numbers, to be transported from one economic zone to another, forced to work and consume for their technocratic managers until they burn-out and can be replaced by more units.

This is the force that will do Man’s design for him if we do not. Art Deco presents an example of a synthesis and integration of the arts that can suit a technological post-industrial society. One cannot, as I feel Paul’s responses reveal, silo painting off from design. The re-humanising force we require needs to rally all its strength, and that includes making buildings with sculptural pieces, making interiors with mural paintings. We need to muster our entire army against the forces of The Nothing!

I am not in fact opposed to us seeking inspiration from other times and places, such as the example Paul gave of the Louis XV style and Rococo. That time had its own synthesis. There is a link between Watteau and the beautiful furniture of that time, incidentally furniture that Jacques-Emil Ruhlmann loved and aspired to match. In fact, for most artists throughout history there has been no separation between the arts. Michelangelo painted, sculpted, and built domes. Many Renaissance artists practiced the arts of the goldsmith as much as the painter. It is a historical anomaly that today’s artists stick to one art, such as painting.

This has led me to the thought that there is an eternal necessity for an integration of the arts against nihilism and degradation. It has always been the case that artists, aesthetes, and patrons, from ancient Egypt to Victorian England, have endeavoured to create a total unity of expression, what is now referred to today prosaically as a ‘style’. It is merely that in our time the forces of dehumanisation, of de-spiritualisation, of the deathening of power, have run amuck and are out of control.

Of course these prior styles were wedded to some kind of transcendent centre, such as a religion or monarchy. Art Deco shows us a modern example of this unified style in a modern, essentially agnostic, society, and that is why we desperately require it. For within that lies the possibility of discovering a form of art and society that can find its transcendence again and, with enough faith in it and ourselves, reach, once again, for the stars.

Sam Wild is Chief Art Columnist for Decadent Serpent. As an artist working in painting and printmaking, he has exhibited in London and Manchester and is an experienced editorial illustrator, creating a long run of covers for The Mallard magazine. He was recently shown at The Exhibition show in Fitzrovia, London. You can find his work here.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Letter to Editor: Sam Wild Responds […]

LikeLike