Author: Sam Wild

I. The Aesthetic of the Unit

In 1952 Le Corbusier finished his Unité d’Habitation and a piece of Western civilisation died. A lot is revealed by names and the ‘Housing Unit’ says a great deal about itself. Before it people lived in homes, now they lived in ‘units’ and by extension they became units. Units in what exactly? This was never really explained but you and your home, and all a person’s life, were reduced to the unit’s rationality — quantifiable, simple, and indivisible.

This was the inevitable result of the phrase ‘form follows function’. For its Modernistic purveyors there was an ethical imperative to be rational about a society’s needs and how design could function to fulfil them. You see, society needed sorting out. It was too irrational, too egocentric, too subjective. The managers of design were duty-bound, out of an innate sense of altruism, to make life ‘work’ for the benefit of all, to make ‘form follow function’. This necessitated the reformulation of the individual and their aesthetic environment to a unit in a managerial system.

In the logic of managerialism the unit’s functions need to be defined objectively. These definitions need to apply to all units, now and always, and therefore the basic functions of all units are the best starting point. In fact, forget all idiosyncratic functions a unit may possess, no resources should be allocated to these perverse preferences. Evidently, a unit is the sum total of all these universal basic functions and all resources should be allocated to these basic functions and to them alone. From this terrible logic we get all of what is innocuously termed ‘Mid-Century Design’.

It is a unique feature of Western civilisation to value the individual; his hopes and dreams, his ideals and moral standards. The struggle of the individual to find meaning in a world that offers infinite possibility is one of the defining characteristics of our culture. Philosophers and historians differ on where this characteristic originates; whether it was the concept of Original Sin versus Free Will that we see in Western Christianity, or the nervous spirit of the barbarian tribes that destroyed the Roman Empire, or the freedom experienced between the dualism of the spiritual and temporal realms in medieval Europe. Regardless of its cause, it is the font of our way of life.

The above Utilitarian logic is a direct threat to that defining characteristic. It is in fact the beginning of a wholly new civilisation. Its culture is one of standardisation and utility. Holy Communion is taken before the spreadsheet and the sole nervous spirit consists of the likelihood of the team meeting next month’s deadline. It is a society of number and control. Prophets like Willaim Blake, John Ruskin and George Orwell saw it in its birth pangs. We see it in its maturity, especially in the skyline of the City of London. It may have swapped its industrial workers and concrete for corporate girlies and open plans but the fundamental logic of the unit remains.

These two civilisations are in an existential battle for the Western soul, indeed for the soul of humanity itself. Superficially, the culture of the West and the culture of Utility may seem related, if not identical. The new civilisation does value all units equally. It does want all units to thrive. Many would mistake this for valuing the individual. The confusion may be understandable as our contemporary utilitarian age is a kind of rationalistic bastardisation of our original ideals. The problem is simply that the real individual, in their fullest sense, cannot be understood as a unit. Our idea of personhood is not one conceived as an object but as a subject, that is, as a thing that thinks, perceives and makes their own choices. As free beings that possess a choice between good and evil we cannot be valued equally. Our idea of the free human being precludes the idea of universal value of all men. There will be sheep and there will be goats on Judgement Day and that gives all a dignity as free agents.

This conflict is as much aesthetic as it is moral or philosophical. Art and life are not separate and the society of the unit has its own architecture, its own art, and its own design. Its ethos is represented firstly in the Bauhaus and later the neoliberal architecture we see all around us, and with this new art so the environment in which our lives play out has been irrevocably changed. The Western soul now finds itself trapped in an ever-expanding panoptical mechanism that seems as omnipotent as it is relentless.

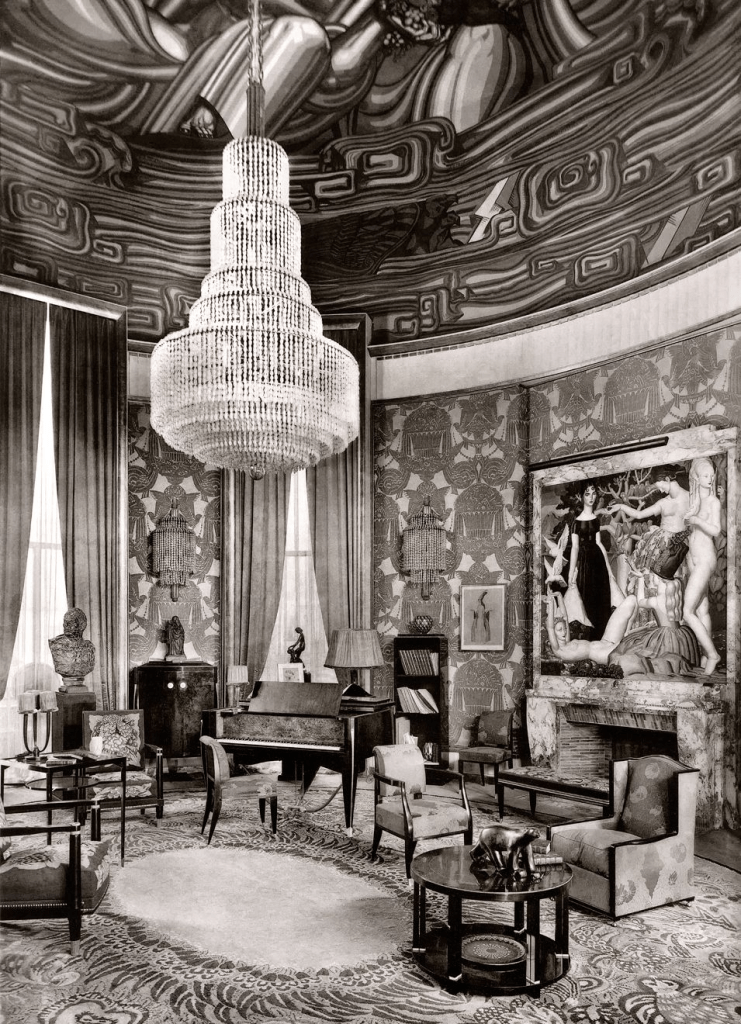

II. Art Deco, the last style of Man

Was it ever thus? This question is a necessity in our 21st century reality. The answer is of course a merciful No. We are compelled to reach backwards in hope of finding a firm grip, to find some sense of real humanity. But where should we look? The art of the past is vast and diverse. If we wander around the museum and look at the history of Western art, what presents us with a viable foundation upon which to revive the spirit of our civilisation? Ancient Greek art? The medieval cathedral? Florentine sculpture? Venetian painting? French Classicism? The choice is dizzying.

There must be some common standard for us all, something that can bring us together for some purpose in the fight against the unit. Of course, each artist and art lover will have his own proclivities and tastes based on that individual’s own personal criteria. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this and, given our valuation of the individual, we ought to allow them to explore and perform their own research, either into truth or error, leaving their work to be the test of their choices. In any case, we are all so different and naturally there is a great deal of disagreement between artists on what aesthetic provides the best basis for art.

That said there is a logical and practical solution to this problem — the last aesthetic before the utilitarian aesthetic took over. As banal and simplistic as this may seem it is worth examining. Time is the great discipline upon men. Our lives are finite and so time itself forces us to make choices out of a seeming infinity of possibilities. Likewise, time orders the progression of our existence. If our purpose is to find the qualities of truly human art is not the most parsimonious choice to examine the last one?

The last truly human style in art and design was Art Deco. This is because Art Deco does not treat the human being as a unit but as subject of thought, feeling, and action.

Firstly, the forms of its sculptors, the designs of its painters, and the plans of its architects reflect a human ambition for modernity. There is a hope and a will in Art Deco to master technology and the fruit of human progress for human purposes. This is crucial. When we see a Deco building we see a building that was first conjured in the mind of an architect, and not the calculated result of processing so many functions. A building is more than that. It is a form. It is a symbol. It is a dream. Crucially, it is for men and women. It is an object with intention. It is not for them in that it serves solely as a place to sleep or as a place to eat. It is for them in that it serves their imagination and their sentiments in its very design. In a sense, it is a part of them.

Now, there is a perfectly respectable case to be made that the Deco ambition and hope in modernity was foolish and mischievous. That is respectable but irrelevant. The point is that it has some humanity to it. A bad boy may be bad but at least he’s a boy and not a robot. Art Deco is a style that is still firmly within the tradition of Western art and its conception of humanity.

Secondly, and related to the first, and as its name suggests, Art Deco is decorative. Art has two aspects, the representational1 and the decorative. Depending on the art form and the artist these two aspects fluctuate but all good art possesses both, and great art fully integrates both. The absence of any decoration from contemporary design is proof of its absolute contempt for humanity. In utilitarian logic decoration is unnecessary because it distracts from function. Also people may capriciously differ on what constitutes good decoration. A person may feel that something is too effete, one may feel something else is brutal and insipid.

It is precisely because of its unnecessary caprice that we must champion decoration! People attach a connotation to decoration. It makes them feel a certain way. It excites them, it delights them, it angers them, it leaves them disappointed. Ultimately it engages them to characterise their experience and evaluate it. It is not a utilitarian calculation of objective output for the mass unit. Decoration is necessary for man to feel a sense of connection and wholeness to the artificial world he must create around himself. To shed it is to alienate man from himself. Art Deco was the last style of any popularity or support that championed decoration, and in that sense it is our last link to that universe of humanity that imagined and felt passionately before the rationality of modernity severed it from us.

Thirdly, it is still familiar to us. We all have ancestors that we knew and that lived in the world of Art Deco, although this is fading. The style lingered on into the 1950s and many of us had elderly relatives that possessed beautiful Art Deco items. In that sense the style is much closer to us than, say, seventeenth century painting, or still medieval art. The people that made Art Deco were like us. They understood the universe and society in a similar way. This is more relevant than we may like to think. As interesting as past cosmologies and religions are, we do live in a world that has seen amazing discoveries in exploration, science and technology. Indeed, these are accelerating. The artists and designers of Art Deco understood what it was like to live in modern society and they insisted on an art that embraced all the human potential that could entail. More than enough lessons for us!

So to conclude, the contemporary interest in Art Deco is necessary in a fight against the forces of nihilism and alienation. The fight is against the utilitarian logic of the managerial society. Art Deco is the last link to a human art in a history that is fragmented and severed. The very concept of Art Deco, of an art of decoration, is essential in our potential to flourish as human beings and essential to us fully flourishing as human beings in a modern society of vast exploration and technological change. Without its memory we are lost to the logic of the unit.

- In the case of architecture, design or craft one can substitute representation for function. So a teapot, or a car, or a post office can perfectly fulfil their function but be spiritually ugly, whereas a good alternative would also be decorative. A truly great piece of architecture and design would actually integrate function and decoration, á la Steve Jobs and the iPhone. Indeed the absence of decoration is part of the whole case against Mid-Century design. ↩︎

Samuel is an artist working in painting and printmaking exploring vitalism and perennialism in art. You can find his work here.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] our chief arts columnist’s piece on The Necessity for An Art Deco Revival was published on Thursday, some of you may have seen a minor disagreement play out on the timeline […]

LikeLike

[…] of a hoo-ha has been stirring in the ether over on X in response to our Art Editor’s recent column and Paul’s subsequent rebuttal. In response we have had others request to throw down their […]

LikeLike

[…] if you wish to read the article which sparked this exchanged you can find it here, along with Paul’s first response […]

LikeLike

[…] have been gladdened by the recent debate caused by my article on the Necessity of the Art Deco Revival. If it has proven anything, it is that there are still men and women out there who care enough […]

LikeLike

[…] The Necessity of an Art Deco Revival (original article) […]

LikeLike