Author: Gavin Duffy graduated from Strathclyde University with an MSc in Historical Studies and has had a general thirst for knowledge from a very young age. His main passion turned towards history which led him to his degree and also his work in museums such as the David Livingstone Birthplace. He has a wide range of interests both academic and non-academic and has a strong belief in exploring the fullness of life and the world.

The meaning and cultural associations of Christmas are something that most people might assume may be universal, images of Santa, reindeer or the more religious trappings of a nativity scene seem to be found wherever Christmas is celebrated, however, even this shows a clash between the religious and secular commercial meanings of Christmas. Throughout the world, various regional customs such as Krampus or Mari Lwyd give Christmas something of a distinct flavour that turns a global festival into a local one.

While these localised versions of Christmas are often just benign festivities, the holiday has a history of being utilised for more nefarious purposes by the regime of the Third Reich in Germany. Christmas was a stone not left untouched by the authorities in their quest for a totalitarian society where National Socialist ideology held principal domain over all aspects of life. The Nazi war to co-opt Christmas had two dimensions that affected their motive for targeting Christmas, and their course of action, both the cultural Germanness of Christmas and the Nazi struggle with organised Christianity.

In his book Christmas in Germany, the author Joe Perry consistently notes that Christmas held a very key position in German culture and that the development and proliferation of Christmas as we know it today was the result of mainly 19th-century cultural developments in Germany.[2] German romanticist writers and thinkers succeeded in attaching a notion that German Christian customs even derived from pre-Christian pagan practices which forged an idea of Christmas as the continuation of millennia of tradition of the German Volk[3]

This German Christmas also influenced festivities further afield. Many of the international symbolic pillars of Christmas such as Christmas trees, markets, and songs were developed within Germany and then spread further afield. Even strong cultural innovations in relation to Christmas from abroad were readily and widely adopted and consumed amongst the German people, such as Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, which became widely popular.

The celebration of Weihnachten had thus cemented itself as part of German life as a festival that could unite the Protestant and Catholic confessional communities whose differences and disputes were a major obstacle on the road towards German unification and thus the religious festival took on a secular socio-political purpose. The fact that Christmas could ironically push a sense of Germanness that triumphed over religious identities made it a key target for the Nazi regime, who were often at odds with the devoutly Christian German populace, to adapt and retarget towards National Socialism.

While the Nazi regime utilised religious messaging for propaganda purposes, they thought both the Catholic and Protestant churches in Germany to be a threat to their regime. This could vary between the individual high-ranking members but devout Christians within the high ranks of the NSDAP were a minority. Some such as Hitler argued in favour of a vague deism that stood against established religion but saw atheism as a sign of Bolshevism and cultural and social denigration, whereas Himmler, and by extension, the SS which lay under his command, were heavily invested in German neo-paganism and occultism. Hitler initially expressed some affection for his own concept of Christian ideals, however, and would utilize this at Christmas gatherings that he personally attended.[4]

The church came under attack from the authorities under what is known as the Kirchenkampf. The goals of the Kirchenkampf were to defang the influence of the Catholic Church, which held considerable political sway, particularly in Bavaria, and to unite the German Protestant Churches under a single National Socialist Reichskirche where Christianity would be enveloped by the smothering and dominant tenets of National Socialism. [5]

The Protestant Churches were a target for more absolute control, as they existed within Germany and were not answerable to a foreign institution, but also that Protestants in Germany were more likely to be Nazis as opposed to Catholics who were more drawn towards the varying Christian parties operating from Bavaria pre-Enabling Act. The Nazis had difficulty in creating a Reichskirche from the top down but Nazis at the base level of the German Protestant Churches joined a powerful movement known as the German Christian Movement which stood in opposition to the anti-Nazi ‘Confessing Church’ in the kulturkampf of Third Reich era German Protestantism.

The regime attempted to utilise the more primordial antisemitism of Christianity in Germany, invoking antisemitic tracts written by Martin Luther himself and playing with sentiments that Jews were a force of modernity, advancing ideologies of secularism and Marxism that the body of Christian believers would have held in distaste.[6]

Neither side held true and total command over the corpus of German protestants with the majority remaining indifferent to either the explicitly pro and anti-Nazi factions within the Church. In spite of this setback coupled with Hitler’s rapid loss of interest in religious control from the early years of the Reich, Christmas was still a key target for the Nazis in their efforts to engulf the total sphere of German cultural life under their ideology.

Nazi policy for culture generally fell under the ‘Amt Rosenberg’ of Alfred Rosenberg or under Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. Both of whom took a key interest in what has been deemed as the ‘Nazi Christmas Cult’, with Rosenberg having the whip hand over much of Nazi cultural policy and Goebbels utilizing his infamous radio broadcasts to deliver tapered Christmas Eve messages towards the public.

The Nazis were able to co-opt the holiday by defining themselves as the defenders of German tradition. The war on Christmas was fought more strongly by the likewise anti-clerical Communist Party of Germany, who in the Weimar Republic took much more militant action against Christmas by attacking Christmas trees and people shopping and celebrating festivities in the street.[7] This allowed the Nazis to paint themselves as the defenders of the popular German tradition which was a surefire way to gain support for their regime. The religious elements of Christmas posed a problem for the regime, however. If the holiday were to be used as a means of propaganda it would have to be ‘aryanised’ and supposed ‘Jewish influence’ would have to be removed.

Other existing customs were presented as a continuation of ancient Teutonic pagan rituals such as Christmas trees which emphasised elements of nature and conjured a mental schema of a purer and simpler German pagan utopia, free of what was seen to be the degenerate influences of modernity.[8] Pagan terms such as ‘Yule’ or ‘Solstice’ were invoked by the Nazis as a means of doing so and while creating a new holiday, attempted to portray themselves as the invigorators of ancient German rituals submerged under a stifling cover of Judeo-Christian aesthetics and values.

One example was Christmas carols, which were either edited to remove and replace lyrics that the Nazis found offensive to their cause, or new ones would be composed. The original German version of ‘Silent Night’, ‘Stille Nacht’ was edited to remove references to the working people, which may have been seen as sympathetic to the Communist or Social Democratic parties in Germany. The Nazis also had their own carols such as ‘High Night of the Clear Stars’ (Hohe Nacht der klaren Sterne) where references to religion were removed and replaced with more secular notions of motherhood, women being seen as mothers was a omnipresent feature of Nazi philosophy regarding women, whether literally or as metaphorical ‘mothers of the nation’ where women were involved in mass Nazi evangelisation.[9]

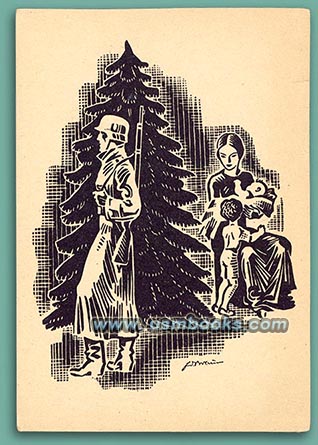

The role of women in the new Nazi Christmas was one of its most eminent features. Christmas was an effective way to mobilise German women and reinforce the pre-ordained Nazi role of women as homemakers and mothers. Also allowing Nazi ideology to bleed past the barriers between public life and the private and more matriarchal domestic realm to fully envelop the lives of those participating in festivities. Women were not necessarily looked down upon in Nazi rhetoric but often exalted with mothers being described as “priestesses” and being described as more connected to the land and spirit of the German Volk than men were.[10]

The connection to women was that they were seen as the heartbeat of the German family, and in turn, the family was the foundation of the Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft. Women were also able to participate in this new Christmas outside the domestic realm.

Women were also fundamental in evangelising the cause of the new National Socialist festivities outside in public. Distributing leaflets which guided families on how to properly celebrate the holiday in a regime-sanctioned fashion drove many women who were members of Nazi organisations to the streets. Other festivities such as Christmas theatre plays, Nazified Christmas markets and charitable fundraising brought a total all-encompassing propaganda drive that merged both private and public and attempted to mobilise the masses of the German population towards active participation in Nazi propaganda drives.[11]

The mentioned mass mobilization of common people, not just soldiers or party officials was key to the propaganda of the communal spirit of Christmas that the Nazis wanted to co-opt. Mass-member Nazi organisations such as the Winter Help Bureau also oversought massive Christmas donation drives towards poorer ‘racial comrades’ which appealed to the charitable nature of Christmas but again in a secularised and Nazified fashion. Groups such as Hitler Youth, League of German Girls and National Socialist Women’s League, all volunteered to collect money in large-scale donation drives, which could number up to 1 million volunteers and dwarfed any previous donation drive such as the ones that were commonplace under the Weimar Republic.

By the time that war had broken out, the utilization of Christmas had also become more militaristic. German production had moved towards weapons and other military logistics so Christmas naturally became a more austere fair compared to the lavish ceremonies beforehand. Families were encouraged to instead send gifts and supplies towards German soldiers on the frontlines, with Goebbels encouraging this in a speech he delivered on Christmas Eve in 1941 and delivered to the German people via radio;

There are few presents under the Christmas tree this year. The effects of the war are evident there as well. We have sent our Christmas candles to the Eastern Front, where our soldiers need them more than we do. Rather than producing dolls, castles, lead soldiers, and toy guns, our factories have been producing things essential for the war effort. Our troops are the first priority.[12]

The wider series of newer Nazi festivals are thought to have had little impact amongst the public. Various festivals were invented under the Third Reich to replace those of old in a not-too-dissimilar manner to that of the French Republic. Very few of these festivals had any purchase amongst the populace, but Christmas differed in offering a new veneer on an existing mass holiday. Notably, Christmas saw mass participation and depoliticising of Nazism in the public sphere as Perry argues.[13] There is a potential counterargument to this that the mass celebrations of Christmas were just a continuation of what was always done but some elements of the Nazi Christmas have continued into the present day.

Some of the Nazi Christmas carols have made an appearance after the war with Hohe Nacht der klaren Sterne having been recorded by the popular schlager singer Heino, and Nazi sympathizer Hermann Claudius’ carols remaining within the hymnary of the German Protestant Church to this day.[14] While not belonging to the major elements of the Nazi Christmas this does show that some of the Third Reich managed to live beyond the downfall of Hitler and into our times today.

SOURCES

[2] PERRY, J. (2010). Christmas in Germany: A Cultural History. University of North Carolina Press p.5

[3] PERRY, J. (2010). Christmas in Germany: A Cultural History. University of North Carolina Press.p.16

[4] Steigmann-Gall, R. (2003). The Holy Reich : Nazi conceptions of Christianity, 1919-1945. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. P.27

[5] Beech, D Between Defiance and Compliance: Reconceptualising the Kirchenkampf 1933- 1945

[6] Follner, M (2020) Culture in the Third Reich p.50

[7] Bowler, G (2016) Christmas in Nazi Germany OUP blogs https://blog.oup.com/2016/09/christmas-in-nazi-germany/

[8] Reagin, N Sweeping the German Nation p.127

[9] Schuring, S. (2014). Mothers of the Nation: The Ambiguous Role of Nazi Women in Third Reich. P.29

[10] Perry, J. (2005). Nazifying Christmas: Political Culture and Popular Celebration in the Third Reich. Central European History, 38(4), 572–605. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141153 p.596

[11] Reagin, N Sweeping the German Nation p.128

[12] Joseph Goebbels Sppech, Christmas 1941 Calvin University https://research.calvin.edu/german-propaganda-archive/goeb34.htm

[13] Perry, J. (2005). Nazifying Christmas: Political Culture and Popular Celebration in the Third Reich. Central European History, 38(4), 572–605. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141153

[14] Jenicker, P (2022) Will a Nazi poet’s Christmas carol remain in book of hymns? https://www.dw.com/en/will-a-nazi-poets-christmas-carol-remain-in-book-of-hymns/a-64184168

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Entry 11 – Christmas under the Third Reich, Gavin Duffy, https://decadentserpent.com/2024/12/24/christmas-under-the-third-reich/ […]

LikeLike