Author: Mat Brown

Crucible of Light: Islam and the forging of Europe from the 8th to the 21st Century is a book about the ‘nature of Europe’s identity’, the ambitious scope of which is conveyed by the subtitle. Dr Drayson (a Cambridge scholar of Spanish) uses the metaphor of a ‘crucible of light’ to describe the complex history of Christian Europe’s relationship with Islam, as she states in the book’s introduction:

The idea of a shared continental culture shatters conventional distinctions between Christian Europe and the Islamic empires and discloses the profound influence of Muslim life on a continent that has been moulded as much by Islamic civilization as by Latin Christendom.

It’s a claim as bold as the scope of the book, and (she states explicitly) an attempt to counter the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ narrative popularised by Samuel P. Huntington, and in response to the changing ethnic and religious mix of our continent. (Professor Huntington, of course, was addressing geopolitics rather than internal state relations.)

Crucible meanders between popular history of the Sultans and Princes, dates and battles variety; discussion of the interactions between Islam and the Christian West in intellectual and cultural fields; biographical tales of travellers, scholars and slaves; and diversions into cities and architecture. It could easily come across as unfocused, but doesn’t; flipping the reader’s attention frequently keeps the book flowing.

The history of Islam in Europe is that of two pincers from the south-west and the south-east, which (rather helpfully) barely overlap in time. Formal Islamic presence on the Iberian peninsular lasted from the first conquests of 711 to the final capitulation of Granada in 1492. In the Balkans, there had been a limited Ottoman presence in Europe for a century before from the middle of the fourteenth century, (Adrianople was renamed Edirne and made the capital), but it only after the final siege of Constantinople in 1453 that the Ottomans really established themselves as a European polity.

These are helpful in framing the narrative of a ‘continual’ presence of Islam in Europe. But the differences are as noticeable as the similarities. There were many Spanish states, from the initial Berber invasions, to the decampment of the last remnant of the Umayyads from Damascus and the establishment of their rival Caliphate, to the final Nasrid holdout in Granada. There were frequent dynastic changes, a result of both the ongoing battle with the Christian kingdoms, and inter-Muslim rivalries often springing from North Africa.

The Ottomans, in contrast, managed to run a largely coherent, united empire. Though constantly in competition on the European front and elsewhere, the dynasty of Osman proved remarkably stable. The early method of a new Sultan ordering the murder of his brothers was brutal but effective; the later method of keeping rivals ‘caged’ in the harem, away from public life less so. But it was an empire which managed to keep strategic focus on its external rivals.

Given this, one might expect that cultural exchange — Dr Drayson’s ‘crucible’ — would have been more likely in Constantinople than Cordoba. Without trying to run counterfactuals across time, a significant factor must be the millet system. The Ottomans managed their different faith communities as self-governing ‘nations’ running with considerable independence over their own communal affairs, such as schooling and (internal) laws. But social and political advancement could only be made by a Muslim. It was a system designed to reconcile the needs of the Empire’s different faiths rather than develop the sort of cultural crossover of the ‘Crucible’; and it worked well, until it didn’t.

Drayson highlights the Armenian Genocide, although her statement that it ‘appeared not to be a religious issue’ as Islam prohibits genocide is spurious. Germany did not tempt the Ottoman Empire into the war ‘with gold and state-of-the art ships’; Germany was reluctant to ally with an empire it feared would be a liability, and in fact it was the seizure of two Dreadnoughts being built by Britain for the Ottomans (Churchill’s idea) which tipped the balance1. And repeating the claim the neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe is in any way ‘Turkish’ is repeating Kemalist propaganda — it predates the arrival of the Turks in Anatolia by something like 10,000 years. It’s on a par with the annual claim that ‘St George was Turkish, actually’.

Still, this is not a convincing argument that Europe as a whole was affected by Islam. The Arabs of Iberia were turned back at Poitiers, and the Ottomans from Vienna (finally) in 1683. It’s good to hear of the tale of the Lipka Tatars in Jan Sobieski’s defence of the Hapsburg capital (in fact Lipkas continued to serve in the Polish army up to the Second World War). Dr Drayson’s claim that Sobieski ‘remains the only European ruler to have established a lasting Muslim community in a non-Islamic European country’ is wrong, though; the Lipkas had been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth for centuries, and whilst he did restore their rights and freedoms, hard-headed politics was as likely a reason as tolerant enlightenment.

One part of Europe that has a long history of interaction with Islam is skated over very briefly — Russia. We have a short sketch of Tatarstan, the Russian republic that is half-Muslim, a legacy of the Kazan Khanate. Dr Drayson calls it a ‘land of tolerance’, mirroring the image that Russia itself presents. Russia had its own orientalists, from Lermontov’s love of the Caucasus to Kuznetzov’s idyllic pictures of Central Asia; and an intellectual tradition embracing Islam as an antidote to Western liberalism. The book covers enough ground seriously to contend with Russia own complex history with her Muslim subjects, but an important frontier of Europe’s interaction with Islam is missed.

Much of Europe therefore had little direct contact with Islam at all, particularly as intellectual and economic power moved northwards. And this can’t be cast as Christian prejudice — for example, the Ottoman were invited to the Congress of Vienna, but Sultan Mahmud II declined. We must fall back on the wider context of ‘cultural exchange’ to establish Dr Drayson’s claim.

The transmission of the Classics through Arabic translations is well known — and along with Abbasid Baghdad, Umayyad al-Andalus is central. It is a tale of Avicenna and Averroes, the astrolabe and portolan, that only the most general reader will not be familiar with, but is always worth telling. In an era of mechanistic translation-by-AI, the immediacy and subtlety of real-world cultural exchanges of a Cordoba or Toledo provide a relevance which would not have been apparent even a decade ago.

The scholars of the Islamic Golden Age were great preservers within the tradition, but (to my mind) there is one thinker who blasts aside the trait of conformism: the historian Ibn Khaldun. Originally from North Africa, he moved to the Nasrid court of Granada, where he came into competition with Sultan Mohammad’s vizier al-Khatib (who is mentioned), before settling in Cairo. An wide-ranging and original thinker, he ‘basically invented what we would now call the social sciences’ (Paul Krugman) and was even cited by Ronald Reagan. His great work, the Muqaddimah, is a study of the cyclical nature of history, and introduces his concept of asabbiyah (group collectiveness) as a driver of imperial expansion — and the loss of it presaging collapse. Perhaps this is at odds with the author’s vision of peaceful multiculturalism, but his omission is glaring.

Crucible’s focus on the Iberia and the Ottomans does not allow much in the way of literary exchanges — it is the Persian poets who have influenced the Western canon from Goethe to Bunting. I must stand up for Dante, who is cited for consigning Muhammad to hell as an example of prejudice against Islam. In fact five Muslims appear in the Commedia: Muhammad and Ali do appear in Canto 28 of the Inferno, the sowers of religious and civil strife — the same circle to which troubadour Bertans de Born is consigned (who Dante respected as a poet). Averroes, Avicenna and Saladin make it into Limbo — as high as a ‘virtuous pagan’ can be admitted (including the poet’s guide, Virgil).

Fortunately, Dr Drayson does not support the Edward Said school of Orientalism, viewing every Western engagement with Islam (and other cultures) as either exploitative or patronising. Pushback against Said is always welcome — the West’s long scholarly and artistic engagement with the East has been (mainly at least) an honest and productive one, for both parties.2

A strength of Crucible is the author’s feel for architecture and place, from the Alhambra’s ‘intentional confusion’ to ‘Venice, the Serenissima, created its own mystique, coming out of the water, rootless, undefined…’ Cultural exchange is demonstrated best through architecture, from the Great Mosque of Cordoba to the imperial mosques of Sinan. (I’m with Charles V, who, on seeing the conversion of Cordoba into a cathedral: ‘You have taken something that was unique in the world and turned it into something mundane.’)

There is no greater gift to Dr Drayson’s cultural exchange than Sinan. We will never know if his origins were Armenian or Greek3, but he was certainly a Christian taken in the devşirme, the Ottoman system of ‘recruitment’ of Christians into the imperial slave Janissary corps. Although brutal, it was also an opportunity for social advancement, and it was not unknown for parents to collude. Contact with families would be broken, and conversion required — Sinan, at the time likely just over 20, would have undergone circumcision. Calling him a ‘European Muslim’ (as the author does) is wrong.

Sinan’s genius is everywhere in Istanbul, from the imperial Süleymaniye to the inventive mosques built for princesses and viziers. His impact on the city is better compared to Wren’s London than Michelangelo. The case for Christian/Muslim interactions in the great age of Ottoman architecture are in fact stronger than Crucible portrays. Whatever Sinan’s origins were, many of the masons involved were Armenian, and the accounts of the Süleymaniye are in Armenian4.

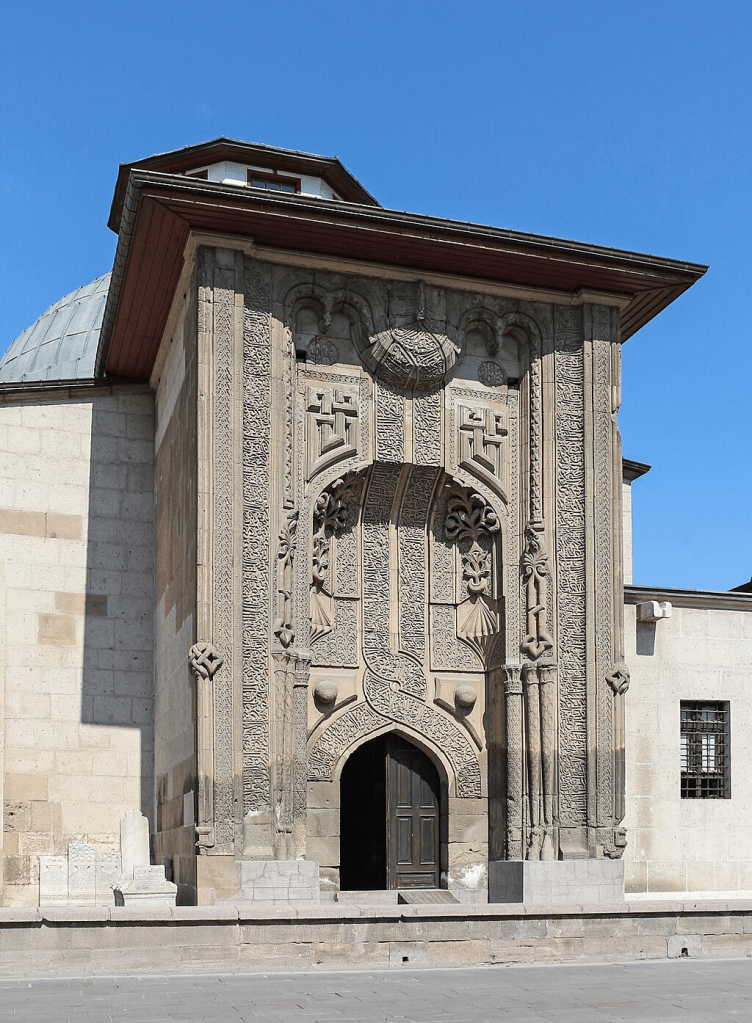

The impact of Christian architects in fact stretches both forwards and backwards in time. Drayson refers to the nineteenth century Dolmabahçe Palace by the Armenian Balyan family; a sense of their prolific output can been seen here. Greeks and Armenians are recorded as dominating architecture in the 18th century5. Beyazit II’s fifteenth century mosque in Istanbul was built by another Armenian convert, Yakubshah6. And before the Ottomans, the Seljuks utilised local architects after they invaded Anatolia after the battle of Manzikert in 1071. Early tombs are near replicas of the domed rotunda of Armenian churches. Names of most of these architects are lost to time, but there are glimpses; the Sivas Gökmedrese was built by a Kaluyan or Kaluk ibn Abdullah, almost certainly a Greek, and the wonderful Inceminerali Medrese in Konya by Keluk bin Abdullah7, seemingly an Armenian.

Crucible both understates and overstates the case. Cultural exchange is important, but it is not the same as multiculturalism. Scholars and monarchs may take a real interest in the exotic for deep or fashionable reasons, and the odd traveller or pirate may go rogue. This is not the same thing as different cultures living side-by-side, day-to-day; as the author quotes (from a nineteenth century traveller in Ottoman Albania) ‘in a state of segregated hostility, which manifested itself in petty crimes, revenge, feuds and murder’.

Islam is not monolithic, any more than Christianity, as Crucible itself demonstrates. The historical experiences it relates are of civilisations living alongside each other for centuries (after an initial invasion, at least). The situation we are experiencing in the West now is different. Drayson depicts immigration as people ‘coming to work’, which is not at all clear; the UK’s principal Muslim communities arrived here as part of a relocation arrangement from Pakistan, and following a war of independence (Bangladesh); followed by chain migration. More recent waves have followed from countries with little or no connection to this country, from Somalia to Syria. It is an unprecedented experiment.

Dr Drayson is even-handed in her history, as happy to record Umayyad renegade Abd al Rahman’s packing fellow Muslims’ heads in salt to send as a message back to Baghdad, or Ottoman Sultan Selim I’s instruction to kill every Shi’ite aged between 7 and 70 in his realms; as any Christian outrages. Roger II’s Sicily is held up as a beacon of tolerance as much as Toledo. Drayson leans on the tiller as she sails through her waters; not unreasonably so, but from a implicit position that it is we — the ‘Latin West’ — that must do the toleration.

Crucible ends with Granada as a model for a tolerant future, but as the author admits elsewhere there were no Christians there by the time it fell. Dr Drayson’s own crucible — an amalgam of culture, history, place and people — is a valuable and wide-ranging book with much interest. The tolerance of the Crucible of Light, though, would seem to be the historical exception, not the rule.

Mat Brown writes on topics as varied as politics, geopolitics, and culture, on his substack. You can follow him on X @fragmentshore.

Crucible of Light: Islam and the forging of Europe from the 8th to the 21st Century is out now and available for purchase.

- The CUP promised the warships to Germany, and likely knew of their seizure before the alliance was signed. See David Fromkin, ‘A Peace To End All Peace’ ( London: Phoenix Press, 1989/2000) p 59. ↩︎

- The topic is covered, superbly and exhaustively, in Robert Irwin’s ‘For Lust of Knowing – The Orientalists and their Enemies’ (London: Allen Lane, 2006), which is unexpectedly missing from an otherwise extensive bibliography. ↩︎

- Leading authority Gülru Necipoğlu leans towards Sinan being Armenian: ‘an Armenian (or perhaps Greek) origin seems more plausible.’ See p 130, ‘The Age of Sinan – Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire’ (London: Reaktion Books, 2005). ↩︎

- Geoffrey Goodwin, ‘A History of Ottoman Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971/2003) p 215. ↩︎

- 5 Necipoğlu, p 157. ↩︎

- Necipoğlu, p 155. ↩︎

- Doğan Kuban, Çağında Anadolu Sanatı (Istanbul: YKY, 2002) p 185, p 170. The patronym ibn/bin Abdullah (literally, son of the slave of Allah) generally signifies a convert. ↩︎

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.