Author: Luke Gilfedder

AngloFuturism, with its vision of fusing the spirit and values of traditional English culture with a futurist passion for technology and the Faustian spirit, is a trend rapidly distinguishing itself from the less-serious novelties of the 2025 zeitgeist. This dialectical ideology, committed to harnessing the optimism and high modernism of early 20th-century avant-gardes, is—as Dinah Kolka observes in her recent review of the Collected Essays on AngloFuturism—a vital sign that counter-movements akin to Vorticism, Futurism, and Dadaism can still thrive today.

One man, however, who might have taken issue with the portmanteau ‘AngloFuturism’ is Wyndham Lewis—a figure many assume to be England’s parochial futurist. Futurism, in its original Italian form, was an avant-garde movement founded in 1909 by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, while Lewis’s Vorticism—established in 1914—is typically regarded as its Anglo-Saxon counterpart. Yet an anecdote from Lewis’s first autobiography, Blasting and Bombardiering, offers a contrasting perspective—one worth revisiting in light of the rise of AngloFuturism. In Chapter II of the book, Lewis recounts meeting his Futurist contemporary, Marinetti, in a lavatory (Marinetti had gone to wash after a particularly vigorous lecture during which he had “drenched himself in sweat”). With characteristic braggadocio, the Italian proclaims that Lewis is a Futurist – and promptly inquires why Lewis has not identified himself as such:

‘Because I am not one,’ I answered, just as pointblank and to the point.

‘Yes. But what’s it matter!’ said he with great impatience.

‘It’s most important,’ I replied rather coldly.

‘Not at all!’ said he. ‘Futurism is good. It is all right.’1

‘Not too bad,’ said I. ‘It has its points. But you Wops insist too much on the Machine. You’re always on about these driving-belts, you are always exploding about internal combustion. We’ve had machines here in England for a donkey’s years. They’re no novelty to us.’

So, where AngloFuturism boldly promises to fuse tradition (‘Anglo’) with Futurism, for Lewis, there is no inherent distinction; hence, no need to romanticise or make a fuss about the ‘Futurist’ half of the equation. It was, in fact, as an act of secession from Italian Futurism that Vorticism established its more ‘English’ identity. While Lewis, like Marinetti, demanded that art be “organic with its time,”2 Vorticism’s aesthetic philosophy—in contrast to Futurism’s hot-blooded, Latin, and “feverish” bluster about the dynamism of modern life (speed, war, and technology)—was immobile, hard-edged, cold-blooded, and ‘Northern.’ Its primitiveness was ‘detached.’ Whereas Futurism felt the machine age “from within, ” Vorticist art regarded its dynamism from the “outside, critically”3—think Troilus and Cressida compared to The Iliad.

The problem with Futurism, as Lewis saw it, was its uncritical enthusiasm for the ‘melodrama of modernity,’ and he characterized the “Futuristic gush” over speed and machinery as making the Latins “the most romantic and sentimental ‘moderns’ to be found.” BLAST went further, mocking the “Ginos of the Future” for their Automobilist artworks—with their careful selection of “motor omnibuses, cars, lifes, aeroplanes, etc.”—as being overly “picturesque, melodramatic, and spectacular,” besides being “undigested” and (like Cubism) “naturalistic to a fault.” Futurism was, to use a later phrase of Lewis’s, a “fanatic naturalism.” Precisely why Lewis chose to assail Futurism with such a philosophically charged term—and sought to counter his continental rivals with a more authentic ‘Northern’ art form—offers insights that are pertinent to the ideology, direction, and ethos of AngloFuturism today.

The ‘nightmare of the naturalistic method’

Lewis’s disparagement of Futurism as “impressionism up-to-date”4, a mere heightened form of naturalism, echoes the criticism made by his acquaintance, T. E. Hulme, who dismissed the Futurist style as simply a “reflection” of the mechanical environment5 (there is no contradiction here: as the German psychologist, Theodor Lipps, observed in Ästhetik, mechanical forces are natural forces).6 In Hulme’s terminology—’borrowed’ from Wilhelm Worringer’s Abstraktion und Einfühlung—Futurism was an extension of the vital or ‘empathetic’ art of Western Hellenic culture and the Renaissance, a naturalistic art expressing a worldview fundamentally opposed to the geometrical or abstract aesthetics of archaic cultures (principally Egyptian, Byzantine, and Oriental, but also seen—to a less profound degree—in Nordic pre-Renaissance art, a.k.a nordische Vorrenaissancekunst).

Vital art, characterised by its organic, emotional, and fluid qualities, sprang from a “more intimate feeling towards the world”7, a “happy pantheistic relationship of confidence”

between man and the flux of the “phenomena of the external world.”8 It corresponds to (i.e., results from and expresses) a confident attitude of continuity, which Hulme believed to be the foundation of humanism, insomuch as humanism regards progress as “an inevitable constituent of reality itself”9, as “independent in its extent and performance as God”10. Whereas the urge towards abstraction is the outcome of a “great inner unrest”11 provoked in man by the transient phenomena of the outside world—operating as it were from a principle of discontinuity—the belief in continuity signifies a complete confidence in the external world, an uncomplicated sense of belonging in the constant flux of nature. Tending to flourish in temperate and agreeable climes, such confidence fosters a feeling of ’empathy’ that gives rise to mimetic representation and “world-revering naturalism”12: because the artist delights in recreating the soft, vital forms of existing things, he resorts to the use of perspective and natural, sensual shapes.

It is little wonder Lewis believed the seeds of the “naturalist mistakes” were to be found “precisely in Greece”13 where this confidence led to a Classical style whose beauty was living and organic, into which the need for empathy—unimpeded by anxieties regarding the outer world—could freely flow. Naturalism, however, as Worringer understood, must be distinguished from mere imitation of the natural world. Naturalism is, yes, the approximation to the “organic and true to life,” but not because the artist wishes to depict a natural object in its materiality faithfully, nor because he desires to give an illusion of a living object, but because his feeling for the “beauty of organic form that is true to life” has been stirred, and he seeks to give expression to this feeling14. In other words, it is the happiness of the dynamic and organically alive—rather than that of ‘truth to life’—that is striven after15. In short, for the Hellenic naturalist, as later for the Futurist, art is objectified self-enjoyment.

This principle, for Worringer and Lipps, crystallises the essence of empathetic art. To enjoy aesthetically means to enjoy oneself in a sensuous object distinct from oneself, to empathise oneself into it, and what the artist emphasises into it is quite generally ‘life’ (energy, striving, and accomplishing—in a word, activity)16. This is why Hulme concludes that naturalistic or impressionistic art necessarily partakes of the flux—in the ephemerality and disorder of the natural world. What Hulme means by this, and by consequently dubbing Futurism the “last efflorescence of Impressionism”17, is encapsulated in a passage from the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting:

The gesture which we would reproduce on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism… it shall simply be the dynamic sensation itself.18

…a principle visualised in works such as Balla’s ‘Speeding Automobile’, Severini’s ‘Blue Dancer’ or Boccioni’s ‘Dynamism of a Football Player’. For the Futurist, everything concrete is in fact, process; everything is involved in everything else (Alfred North Whitehead, one of Lewis’s philosophical bête noires, called this ‘organic mechanism’)19. Simply put, Futurism differed from Impressionism in emphasis only: whereas Impressionists analysed colour to capture the elusive qualities of light, Futurists examined motion to capture moving forms.

Akin, however, to the naturalists of Worringer’s Classical-Hellenic tradition, the Futurists did not seek simply to imitate the new nature of the dynamic machine world. Acting as nature’s amplificationists, their objective was to project the lines and forms of the organically vital, the euphony of its rhythm—in fact, its entire inward being—outward, to “furnish in every creation a theatre for the free, unimpeded activation of one’s own sense of life”20—thus allowing the spectator to experience gratification through the mysterious dynamism of organic form, in which one could enjoy one’s own organism more intensely. Given Lewis’s aversion to the use of “infantile or immature life” in art and his despisal of ‘the fluid’21, it is hardly surprising that, several months after Hulme’s lecture, BLAST declared: “We are not Naturalists, Impressionists or Futurists (the latest form of Impressionism).”22

‘Impressionistic Fuss’

The rejection of Impressionism, which the Italian avant-gardists were keen to emphasise, held little weight for Lewis: he maintained that Futurism, with its naïve enthusiasm for machinery and the ‘modern’, merely parodied Wilde and Gissing, being a “sensational and sentimental mixture of the aesthete of 1890 and the realist of 1870”23.

“Wilde gushed twenty years ago about the beauty of machinery,” BLAST quips, “Gissing, in his romantic delight with modern lodging houses, was futurist in this sense”24. Like Hulme, Lewis saw little distinction between the naturalist aims and techniques of late 1800s Impressionism and the arbitrarily named Post-Impressionist movement, which included Divisionism as a variant and which was claimed as a crucial element of Futurist aesthetics.25 Regardless of its ‘anti-pastist’ intent, bothHulme and Lewis felt that Futurism differed only in degree, not in kind, from the norms that had prevailed in European art since the ‘heresy’ of the Renaissance, and shared the same defects: the same superficial and “insipid”26 optimism rooted in a purely illusory confidence in continuity (the “flowing lines” and “absence of linear organisation” revealed, in Lewis’s words, an “inveterate humanism”).27 It was against this far-reaching tradition—stretching back to the ancient Greeks, those “Gods of the Renaissance”28—that Lewis believed we should turn to the Classical Orient (in the “sense of Guénon”) for reprieve29.

The abstraction Hulme and Lewis sought to revive—which permeated the ancient world and was most perfectly embodied in the Guénonian Orient—was a tradition that resulted instead from an immense spiritual and primitive fear elicited in man vis-à-vis the phenomena of the external world, an instinctive feeling of alienation and dread that the rationalistic development of mankind had gradually suppressed. As Worringer states, only the civilised peoples of the East—whose more profound world-instinct resisted man’s development in a rationalistic direction, and who perceived in the material world only the shimmering veil of Maya—remained tormented by the disjointed, bewildering, arbitrary flux of life, the relativity of all that is, and “all the intellectual mastery of the world-picture” could not denude them of this worldview30. Their subsequent calling, as Lewis later wrote of his own profession, was “to solidify, to make concrete, to give definition to… to postulate permanence.”31

While the Futurists accepted today’s ‘nature’ wholesale (“their paean to machinery is really a worship of a Panhard racing-car”32), the ideal mechanical art envisioned by Hulme would more closely align with the geometrical arts of the ancient past, both in style (adapting the “intensity” of Byzantine mosaics, with their “rigid lines” and “dead crystalline forms”) and sensibility (being an objective, absolute machine art that embodies a “disharmony” or “separation between man and nature”33). Unlike the naturalist impulse towards empathy—which finds its fulfilment in the beauty of the organic—this more primitive urge towards geometric abstraction sought beauty in the life-denying inorganic, in pure geometric regularity, and more broadly in all abstract laws and necessities.

For Lewis’s friend, Ezra Pound, the early paintings by Lewis and the sculptures of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska exemplified a modern art that imbibed this spirit, liberating the imagination from the overly familiar world of the organic into one of semi-abstract forms and “planes in relation”34. Take, for instance, Brzeska’s marble portrait of Pound—commissioned by Pound himself—which subdues the poet’s vaguely Nordic features and ziggurat hair into simple geometric planes until he resembles an Easter Island statue.

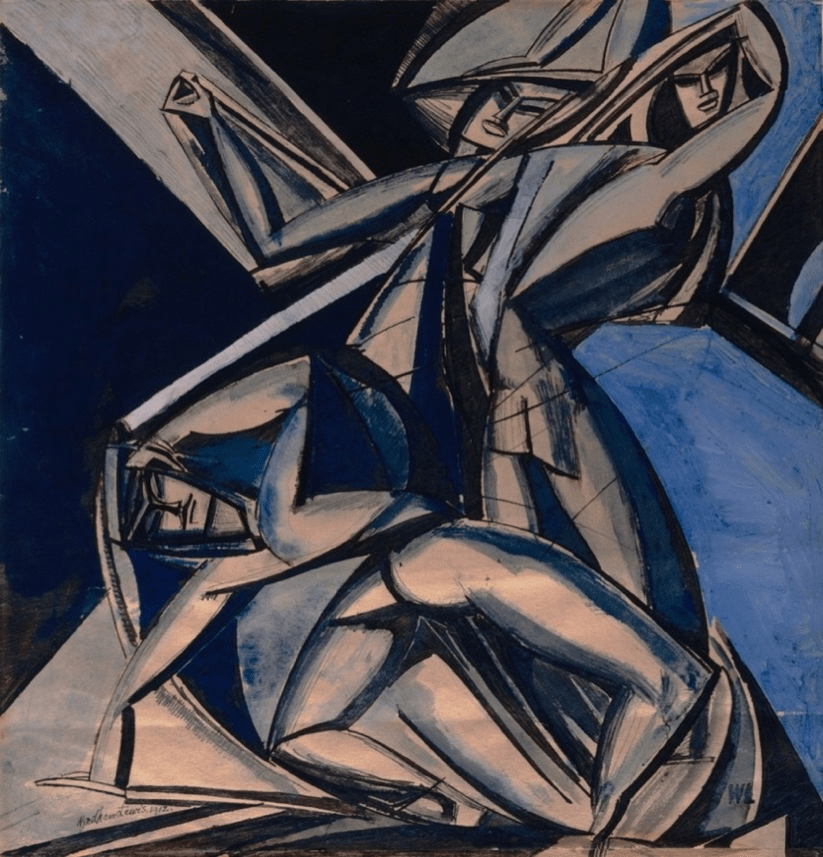

The crucial move for Vorticism, in establishing its ‘Northern’ aesthetic philosophy, was to apply this juxtapositional, spatial model to ways of thinking about time. A few months before the launch of BLAST in 1914, Hulme delivered an influential lecture at the Quest Society on Modern Art, wherein he described Byzantine mosaics, the pyramids of ancient Egypt, and the figures and masks of ‘primitive’ tribal cultures as examples of artworks embodying his desired principle of discontinuity: the impermanence of the outside world, Hulme said, incited either dread or disgust in the archaic artist, prompting him to seek refuge in abstraction, in perfection and rigidity, in stable monumental shapes. In contrast to naturalism’s humanistic confidence in change, these abstract works wrested the object out of its natural context, out of the flux and contingency of the organic world, and strove to impose upon it the stamp of eternalness. As Lewis was commended in Hulme’s lecture as an exemplary practitioner of this new “constructive geometrical art”35, there is good reason to believe that he was aware of it and was influenced by it in departing from Futurism and establishing the angular, anti-vitalist style of Vorticism.36

The Great English Vortex

The dictionary defines a vortex as a whirling mass of water or air, and one might presume, from subsequent references to lines of flow, spirals, curves, and rings, that a movement calling themselves Vorticists would have produced an art that was certainly curvilineal and possibly soft-edged, evoking the fluidity and rotation characteristic of whirlpools and whirlwinds. Yet Vorticism—in contrast to the swirling patterns and compositional turbulence of Futurism—adhered to a rigidly geometrical, sharply delineated aesthetic of “diagonals, zig-zags and verticals.”37 Rejecting Futurism’s machine-idolatry and its proto-accelerationist exaltation of speed and change, the Vorticists, as Marshall McLuhan observed, instead sought to “arrest the flux of existence” so that the observer could be “united with that which is permanent.”38 As opposed to the “sentimental Future” as it was to the “sacripant Past,”39 Vorticist art “plunges to the heart of the Present”40 to create an aesthetic concretisation of time that momentarily disrupts the “insistent, hypnotic” rhythm of the mechanical world around us.41

Declaring themselves not “the Slave[s] of Commotion but its Master[s]”42, the Vorticists harnessed the tension between the formalism (and “static monumentality”) of Cubism and the “kinetic dynamics” of Futurism43, bringing to the foreground the stillness that resides at the heart of all movement—hence the foundational metaphor of the vortex, a “circulation with a still centre.”44 Vorticism was, in other words, “a dynamic formism”45, and the Vorticist at his “maximum point of energy when stillest.”46 In place of Futurism’s fetishisation of the new “beauty of speed,”47 la bellezza della velocità— which had the effect, in Futurist canvases by Balla, Severini, and Boccioni, of disrupting Lewis’s aesthetic preference for the Oriental rigidity of outline with blurred and multiple images—the Vorticists offered a controlled energy. Their machine aesthetic was a necessary vertebration of Marinetti’s “impressionism and sensationalism”48, tempering Futurist melodramatics with Cubist sobriety, “Italian movement” with “French monumentality.”49 Where Futurist paintings were “swarming, exploding, or burgeoning with life,” Vorticist art was “electric with a more mastered, vivid vitality.”50

Vorticism’s jagged forms, sharply delimited by straight lines or geometric arcs, thus betokened a classical search for control and rationality in contrast to the fluid and imprecise approach of Futurism, which Lewis considered a continuation of the modernist “disorder” of Nineteenth Century ‘romantic’, ‘revolutionary’, European thought.51

For Lewis, the vortex could thus be defined as a “great silent place” at the “heart of the whirlpool” where “all the energy is concentrated.”52 It was not a flux but a “dynamic, moving image” related to time but also “containing a stable point, the spatial element from which its “energy spirals originate.”53 But where Lewis’s vision of the vortex was centrifugal, the Futurist’s was centripetal, with “force-lines” that “encircle and involve the spectator so that he will […] be forced to struggle himself with the persons in the picture.”54 Positioning the spectator at the ‘centre of the picture’, making him ‘live’ in that convergence of flux, in a participative role, was a recurrent theme in Futurist theory: “all things move, all things run, all things are rapidly changing,” states the Manifesto tecnico, “we would at any price re-enter into life.”55

Russolo’s The Revolt (1911) transposes this declaration onto the canvas, employing energetic brushstrokes, triangular wedges, and a vibrant colour palette to capture the “emotive force” of revolutionary violence and “forcibly oblige the spectator” to be at the “centre of the painting”56, to relive the fervour of the advancing mob. This urgent call for supplementary activity on the part of the spectator—the appeal to subjective experience—stood in direct contradiction to the ancient world’s need for abstraction. In the urge to abstraction, the intensity of the self-alienative impulse predominates: ‘LIFE,’ for the archaic artist as for Lewis, was felt to be a disturbance of aesthetic enjoyment.

In contrast to Futurism, Vorticism’s jagged forms—sharply delimited by straight lines or geometric arcs—thus signified a classical search for control and rationality, and were a pointed rejection of the fluid and imprecise approach of the Italian avant-garde, which Lewis considered a continuation of the modernist “disorder” of Nineteenth Century ‘romantic’, ‘revolutionary’ European thought.57 Observe how the ‘revolt’ depicted in The Crowd—where the French and Communist flags of the stick figures symbolise the various doctrinaire revolutionary ideologies of modernity—is presented by Lewis not as a vitalistic surge (as seen in Russolo’s painting. but as a mass of busy-bodying automatons “strut[ting] and pant[ing] in insect packs”58, indistinguishable from one another and from the mechanical metropolis that ‘enframes’ them.

Lewis’s denigration of Futurism as ‘romantic’ stems from his Hulmean interpretation of Romanticism not as a period but as a philosophical approach: Romanticism meant temporality and the myriad social ills Lewis associated with it: everything “romantically ‘dark’, vague, ‘mysterious’, stormy, uncertain”.59 Classicism, conversely, meant everything nobly defined and exact (the Hellenic, for Lewis, held no monopoly on the ‘classical’). Futurism was thus ‘Romantic’ for fetishising flux, speed, and dynamic action, while Vorticism was ‘Classical’ in emphasising detachment and the hard-edged forms of space. Romanticism possessed a similarly sweeping and negative connotation in Hulme’s thought: it represented nothing less than the artistic expression of the humanistic conception of man that had prevailed since the Renaissance (evolving, as it were, in a straight line from Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man to Rousseau). We have already noted that Hulme perceived Western humanism— the “slush in which we have the misfortune to live”—as intellectually insipid compared to the stark, “uncompromising bleakness” of Indian philosophy, just as he regarded Western naturalism as decadent and “anaemic” next to the angular hardness and bareness of Egyptian and African art60. Hulme’s principal contribution to modern British art, however, lay in linking these static Oriental and primitive worldviews with the emerging preference for the austere, hard, clean and ‘bare’ aesthetics evident in the works of certain contemporary British artists, thus endowing the new mechanical art with a vision of its traditions and its place in history.61 “Austerity” and “bareness” were the traits Hulme applauded in the work of Lewis and Jacob Epstein, and these, he stressed, were the “exact opposite” of Futurism (a descendant, instead, of the ‘Occidental’ romantic tradition).62

By presenting the austere geometric works of the Rebel Art Centre painters—including his own—as a distinctly Anglo-Saxon or ‘Northern’ artistic expression, Lewis was thus able to distinguish Vorticism from Futurism. The English were the “inventors of this bareness and hardness”, he proclaimed in BLAST, “and should be the great enemies of Romance.”63 After all, the English could accept the machine without the Futurist’s “propagandist fuss”64:

England practically invented this civilisation that Signer Marinetti has come to preach to us about. While Italy was still a Borgia-haunted swamp of intrigue, England was buckling on the brilliant and electric armour of the modern world and sending out her inventions and new spirit across Europe and America.65

Unlike all the ‘hullo-bulloo’ of Marinetteism about motor cars “more beautiful than the victory of Samothrace”66, ‘the art for these climates,’ the Vorticists asserted, must be a “northern flower.”67

Lewis follows Worringer in contrasting the lively naturalism and romanticism of early Southern European art with the Gothic formalism that flourished in the North, whose people had no “clear blue sky” arching over them, no serene climate, and no “luxuriant vegetation” to induce in their souls a “world-revering pantheism.”68 Faced with a “harsh and unyielding” nature, Northern man experienced not only the resistance of the environment but also his isolation within it, and so confronted the phenomena and flux of the outer world with a sense of “disquiet and distrust.” For Lewis, the “natural magic” of Western poetry derived its “peculiar” and penetrating quality from these “intense relations” of the Western Mind to the “alien” physical world of “nature.”69 He therefore urged his fellow artists to “ONCE MORE WEAR THE ERMINE OF THE NORTH” and even advocated for the return of “necessary blizzards” to reawaken that primitive sense of deep dread before nature—the disharmonious état d’âme that first compelled Northern man towards rigid lines and inert crystalline forms, rather than to the naturalistic and organic forms of the South.70

That Vorticism remains a less influential movement than Futurism—being little more today than employment for art historians—doubtless speaks to our ongoing fetishisation of the south, of the sun, of “bright Latin violence and directness”—la gaya Scienza.71 For Vorticism, unfashionably, typified Worringer’s observation that Northern art aims to ‘de-organicise’ the organic, to translate the mutable and conditional into values of unconditional necessity.72 As with the Classical-Orient cultures Lewis praised for emphasising the hard-edged forms of space and the “immediate and sensuous… the ‘spatial’”73, the art of the Celto-Germanic North strove to suppress every element of the organic by approximating it to a pure linear regularity. The happiness they sought from art did not lie in projecting or empathising themselves into objects of the outer world, but rather in wresting the object out of the external world, out of the unending flux of being—purifying it of its dependence on life and everything temporal or arbitrary—and elevating it into the realm of the necessary; in a word, to eternalise it. This, Lewis asserts, is the heritage being repudiated in the present ‘time’ modes—a repudiation that shows no sign of abating today.74

Conclusion

Vorticism’s defence of its Northern heritage can be seen as a proclamation of Lewis’s essentialism—his counter-propagandistic belief in ‘essence’ as opposed to ‘being’ and ‘becoming’—an essentialism expressed in Time and Western Man’s preference for Parmenides, who emphasised the unchanging and eternal nature of reality, over Heraclitus, the “weeping philosopher”, who proposed that there is “nothing but dissolution and vanishing away, so that the river into which you step is never twice the same river, but always a different one.”75 It was this Heraclitean view of energy and force that the Futurists extolled, but for the Vorticists, as for Lewis’s Tarr, “Art is identical with the idea of permanence… Anything living, quick and changing is bad art always”.76 The artistic imagination, like the intellectual vision, should be devoted not to energy but to the Apollonian search for form: “to crystallise that which (otherwise) flows away, to concentrate the diffuse, to turn to ice that which is liquid and mercurial.”77

But surely, as Northrop Frye protests, art is energy incorporated in form—the energy rhythm, the form plasticity.78 Overemphasis on one leads to a surging Heraclitean chaos; overemphasis on the other to a frozen Parmenidean one. Yet both these, as Frye suggests, are essentially the same thing: the root of evil in art lies in the “unfortunate tendency toward the abstract antithesis,” toward the composition of cheap epigrams which “minor critics revel in” and serious artists avoid.79

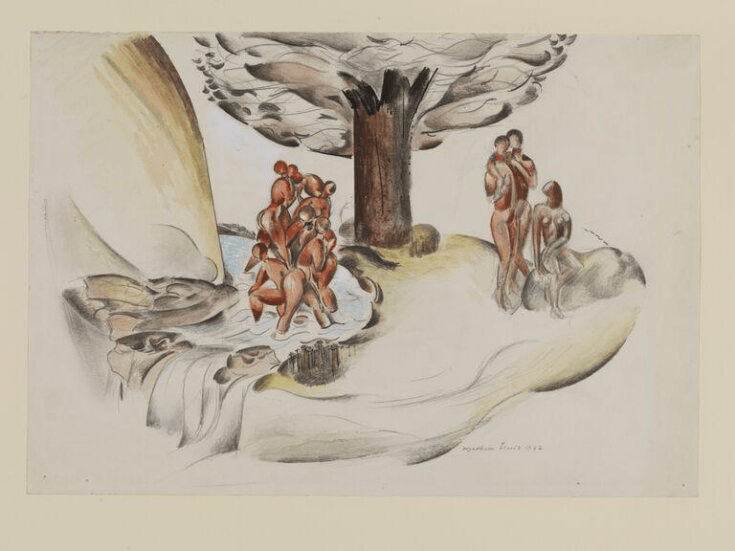

Lewis, of course, was alive to this charge, as evidenced by a series of late-career ‘sea images’, nudes and bathers, painted in the mixed idiom of “pure-abstraction-and-stylized-nature”80 (he even pronounced the death of purely abstract art in 1939 and declared himself a “super-naturalist”)81. Yet this collection of brilliant watercolours, with their cloudy, watery spaces and huge, floating marine shapes—regarded by Walter Michel as the “imaginative and gayest” of Lewis’s career and his most ‘human art’ to date82 — only make plain what Lewis had always considered to be the true relation between the artist and nature. He held the traditional view of imitation as working in the way nature works, with all the “beauty of accident”, but without the “certain futility that accident implies,”83 so that art becomes, in a sense, another nature.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, to find in the sketches for these Etty-inspired nudes a stark Vorticist geometry still underlying Lewis’s newly flowing lines. Even as a super-naturalist, Lewis never revoked Tarr’s dictum that “Deadness is the first condition of art,” a deadness based upon “the absence of soul, in the human sentimental sense”84—this was why Vorticism first invoked the ‘abstraction’ of all the Pharaohs and Buddhas, our world of “matter,” against the “Einsteinian, Bergsonian or Alexandrine world of Time and “restless” interpenetration.”85 But Lewis’s fluminous 1940s paintings — these semi-abstract fantasies of “worlds moving round together in a chaotic corner of creation”86 — reveal that the Vorticist view of art was never a cold or mechanistic rationalism, as Frye’s critique implies. Art was the product, yes, of the “purest consciousness”87, of the open eye, the open senses: the conduits to the constructing, shaping mind. But the producing, the actual act of creation—that, Lewis always believed, was strictly the ‘work of a visionary’:

… Shakespeare, writing his King Lear, was evidently in some sort of a trance; for the production of such a work, an entranced condition seems as essential as it was for Blake when he conversed with the Man who Built the Pyramids.88

But if art is a “spell, a talisman, an incantation”, Lewis nevertheless insisted it was strictly a civilised substitute for magic89, a distinction he makes explicit:

A great artist falls into a trance of sorts when he creates, about that there is little doubt. [Yet while] the act of artistic creation is a trance or dream-state, [it is] very different from that experienced by the entranced medium.A world of the most extreme and logically exacting physical definition is built up out of this susceptible condition in the case of the greatest art.90

A different matter, then, from any creative automatism or from the blind art of flux, with its vitalist outpourings of the “hot, immediate egoism of sensational life”91 and its “surging ecstatic, featureless chaos”, which is “being set up as an ideal, in place of the noble exactitude and harmonious proportion of the European scientific ideal.”92 It was this severer conception of great art that Vorticism employed to construct its nationalist avant-garde programme, making it more than just a parochial attempt to emulate Futurism. As BLAST asserts, what is actual and vital for the South is “ineffectual and unactual” in the North.93 This is why Vorticism—and not its continental counterpart—provides the most congruent aesthetic philosophy for new British art, and for contemporary Anglo-Saxon movements seeking, in a high modernist spirit, to “fuse national tradition with a futuristic drive for rapid technological progress.”94

Perhaps it is not necessary to stress the distinction: as Lewis himself admitted, ‘Futurist,’ in England, signifies nothing more than a painter concerning himself with the renovation of art, of capturing futurity, or rebelling against the domination of the Past.95 Nevertheless, Vorticism—with its “bitter Northern rhetoric of humour”96—remains not only the original but the true ‘Anglo-Futurism’. After all, it needs no prefix.

Luke Gilfedder is a writer and Modernist scholar from Manchester. He is set to launch his debut novel, Die When I Say When, later this year—extracts of which have appeared on Decadent Serpent, The Brazen Head, and in Corncrake Magazine. His first non-fiction book, Wyndham Lewis: Modernism and the New Radical Right, is due to be published shortly by Logos Verlag Berlin.

- W. Lewis, Blasting and Bombardiering (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1937), 37. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 34. ↩︎

- W. Sypher, ‘A Mechanical Operation of the Spirit’ (1977) The Sewanee Review 85(3): 512–519, 513. ↩︎

- Ibid., 143. ↩︎

- T.E. Hulme, Speculations: Essays on Humanism and the Philosophy of Art, ed. by H. Read (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, 1924), 109. ↩︎

- T. Lipps, Ästhetik: Psychologie des Schönen und der Kunst: Grundlegung der Ästhetik (Hamburg: L. Voss, 1903). ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 93. ↩︎

- W. Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style, trans. by M. Bullock (Chicago: Elephant Paperbacks, 1997; originally published 1908), 15 ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 3 ↩︎

- S. Spender, The Destructive Element: A Study of Modern Writers and Beliefs (London: Jonathan Cape, 1935), 202 ↩︎

- Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 15. ↩︎

- Ibid.,45. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, Paleface: The Philosophy of the Melting-Pot (London: Chatto & Windus, 1929), 255. ↩︎

- Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 27–28. ↩︎

- Worringer (paraphrasing Lipps) argues that for empathetic artists the value of a line or a form consists principally in the “value of the life” it holds for them; it possesses its beauty only through their own vital feelings, which, in some “mysterious manner”, they project into it (Ibid., 14). ↩︎

- Ibid., 5. ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 94. ↩︎

- U. Boccioni, La pittura futurista. Manifesto tecnico (Milan: Governing Group of the Futurist Movement, 1910), p. 1. ↩︎

- A.N. Whitehead, Science and the Modern World: Lowell Lectures, 1925 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1925). ↩︎

- Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 28. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 69. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 7. ↩︎

- Ibid., 8. ↩︎

- Ibid., 8. ↩︎

- Bracewell, Space, Time and the Artist: The Philosophy and Aesthetics of Wyndham Lewis, PhD thesis (University of Sheffield, 1990), 256. ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 80. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, Men Without Art (New York: Russell & Russell, 1964), 127. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, The Lion and the Fox: The Role of the Hero in the Plays of Shakespeare (London: Methuen & Co., 1951), 262. ↩︎

- Lewis, Paleface, 255. ↩︎

- Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 16. ↩︎

- Lewis, Paleface, 254. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, The Caliph’s Design (London: The Egoist, 1919), 29. ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 87 ↩︎

- E. Pound, Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir (Hessle: Marvell Press, 1960), 92. ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 103. ↩︎

- Lewis frequently denied Hulme’s influence on his work and even reversed the sequence of events in his first autobiography, asserting that “I did it, and he [Hulme] said it” (Lewis, Blasting and Bombardiering, 106). ↩︎

- A. Munton, ‘Rewriting 1914: the Slade, Tonks, and war in Pat Barker’s Life Class’, in M.J.K. Walsh, ed., Modernism and 1914, *Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 265. ↩︎

- M. McLuhan, ‘Wyndham Lewis: His Theory of Art and Communication’, in Theories of Communication (New York: Peter Lang, 2011), 10. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 9 ↩︎

- Ibid., 147. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 42. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 148. ↩︎

- R. Cork, Vorticism and its Allies (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1974), 22. ↩︎

- H. Kenner, The Pound Era (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1971), 239. ↩︎

- R.W. Dasenbrock, The Literary Vorticism of Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis: Towards the Condition of Painting (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), 41. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 148. ↩︎

- Marinetti, Manifesto del Futurismo, 4. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 213. ↩︎

- R. Cork, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age (London: Gordon Fraser, 1975) cited in M. Wutz, The Energetics of Tarr: The VortexMachine Kreisler (MFS Modern Fiction Studies, 1992), 865. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast 2, 38. ↩︎

- Lewis, Paleface, 255. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, ‘A World Art and Tradition,’ Drawing and Design, 5/32 (1929), 56. ↩︎

- E. Lamberti, ‘McLuhan’s Media Explorations through the Rear-View Mirror: Vortexes, Spirals, and Humanistic Training’, Theoretical Studies in Literature and Art, 35/1 (2015), 79 ↩︎

- Exhibition of Works by the Italian Futurist Painters, exhibition catalogue, (London, Sackville Gallery), 1912, 14. ↩︎

- Boccioni, Manifesto tecnico, 1-2. ↩︎

- M. Antliff, Inventing Bergson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 164. ↩︎

- Lewis, Paleface, 255. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, Collected Poems and Plays, ed., A. Munton (New York: Routledge, 1979), 79. ↩︎

- Ibid., 255-256. ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 80. ↩︎

- Parker, ‘Some Portraits of the Artist’, 24. ↩︎

- Hulme, Speculations, 96. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 41. ↩︎

- Lewis, Wyndham Lewis the Artist, From “Blast” to Burlington House (London: Laidlaw and Laidlaw, 1939), 79. ↩︎

- Lewis, The Art of Being Ruled, 33-34. ↩︎

- Marinetti, Manifesto del Futurismo, 3. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 36. ↩︎

- Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 107. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 271. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 12. ↩︎

- Lewis, Men Without Art, 21. ↩︎

- Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, 43. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 406. ↩︎

- Ibid., 271. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 247. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, Tarr, ed., S.W. Klein (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 264. ↩︎

- Lewis, Paleface, 254. ↩︎

- N. Frye, ‘The Diatribes of Wyndham Lewis: A Study in Prose Satire’ in R.D. Denham, ed., Northrop Frye’s Student Essays: 1932–1938, vol. XXIX of The Collected Works of Northrop Frye (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 380. ↩︎

- Frye contends that Blake, for instance, defended the importance of outline “even more vigorously” than Lewis did, but made it clear that, to him, form was always the “incorporation of energy” (Ibid., 363). ↩︎

- Lewis, Letters, 504. ↩︎

- W. Lewis, Wyndham Lewis the Artist, 504. ↩︎

- W. Michel, Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings (London: Thomas and Hudson, 1971), 136–142. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast 2, 75. ↩︎

- Lewis, Tarr, 265. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 453. ↩︎

- W. Lewis cited in R. Stacey,‘“Magical Presences in a Magical Place”: From Homage to Etty to The Island’ in C M Mastin, T Dilworth and R Stacey, eds., The Talented Intruder: Wyndham Lewis in Canada, 1939–1945 (Windsor, Ontario: Art Gallery of Windsor, 1993), 119. ↩︎

- Lewis, Time and Western Man, 39. ↩︎

- Ibid., 198. ↩︎

- In Time and Western Man, Lewis significantly wrote that to eternalise, to “make things endure” is “a sort of magic” and a “more difficult one, than to make things vanish, change and disintegrate” (Ibid., 372). ↩︎

- Ibid., 129. ↩︎

- Ibid., 271. ↩︎

- Ibid., 129. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 34. ↩︎

- A. Roussinos, ‘Could Anglofuturism liberate Britain? Westminster needs some of Donald Trump’s optimism’ UnHerd, (27 Jan. 2025), https://unherd.com/2025/01/could-anglofuturism-liberate-britain/, accessed: 20 February 2025. ↩︎

- Lewis, Blast, 143. ↩︎

- Ibid., 26. ↩︎

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.