Author: Amory Crane

You can listen to the audio version of this article here:

All art is power speaking to itself. Only once it has consolidated does it turn to face the ruled.

The question of art today is a curious one. On the one hand we are familiar with the usual objections: too woke, too derivative, too incestuous; yet there is, despite a contrary yearning, very little which has presented itself as an alternative. In politics, going back to those halcyon days of the ‘pre-woke’ is clearly what is being signalled by certain aspects of the prevailing culture. Curious then that ‘Derivative Politics’ is a phrase singularly absent from our political lexicon. This, I maintain, is no bad thing. Yet for all those clambering for a return to the ‘sanity’ of yesterday, the day before our current insanity; to ask them if we could return to pentameter verse as the ubiquitous form of dramatic expression would seem mere nostalgia — or worse: absurd affectation. That the recycling of old subjects and modes of presenting reality are, curiously, most often taken as the obvious signs of a society’s entropy can only be explained by observing, as Ezra Pound once did, that ‘artists are the antennae of the race’. Yet the fact that today’s art has become tired, peripheral, lax, is not, as I shall make clear, the simple matter of a lack of desire to innovate. If a culture is alive, if it is hot-blooded and bristles with confidence in itself, it may return again and again to the same theme with unattenuated vigour. It is precisely a society which ceases to explain itself successfully, when its inconsistencies are everywhere apparent even to its chief adherents, that its art atrophies. Then, with each reiteration of the same forms they lose whatever handle on eternal truth they once may have had, and like a debased coinage are left bereft of what once made them valuable in the first place.

It is not then, to be clear, a lack of originality, but the inconsistencies in Power’s myths which wear thin the cord between energy and art. For great art reconciles eternal truths to where the conditions of the day have made them obscure: it is in this way both contingent and perpetual. This explains why the art of today is so tedious, so blind to modern man’s search for meaning and, in a word, so thin. When Power loses grip of its reasons to perpetuate itself beyond its own sake, of reconciling itself to deep truths, then art too loses touch with those essential truths with which it must maintain itself. In the vacuum, rival powers may emerge.

The aim then, is to show how these main criticisms — engagé, derivative, incestuous — and others adjacent are not really criticisms at all, least of all distinct ones. Instead, beneath all of them is a simple unifying factor, which has remained obscure until certain ideas, long obscured and ‘lost’, have returned to the fore of our minds. I am talking here of that single most exciting development in political thought over the past five or so years which has been the renaissance — and this is the operative word — in a body of knowledge which has found its common expression in the name Elite Theory. For in returning, this ‘new learning’ (read old) has made certain things for a certain minority of people untenable: the revival of pre-nineties neoliberalism, of a frame of reference and education that blinded even the best minds of a generation until the stark incongruences of presented reality forced them to see. In other words, the growing clarity among certain groups of people of this state of affairs has put real questions over the very possibility of such a ‘Return to Fresh Prince’; and if Power cannot turn back this clock without withering its vitality neither, in the last analysis, can Art. For Art is Power speaking to itself. Only once it has consolidated does it then turn to face the ruled.

Let us look at any one of those criticisms then — that it is derivative, say — and show how this has been the case.

For centuries the two main subjects of art were biblical stories and incidents from Greek mythology. Yet curiously, even when it innovated, art returned to these same subjects again and again with no sense of enervation. This is because the subjects themselves were tolerated, even approved of by each iteration of Power, but the manner in which they were seen was not. Each ‘circulation of elites’, to refer to a concept of Pareto’s, necessitated a change of aesthetic, which is to say, the way we see is conditioned by Power, and changes only when new insurgent powers coagulate. Feudal times, for instance, when the position of the individual at the centre of his world would have been a ludicrous proposition, are notable for their recycling of myth. These myths are concerned less about human choice and agency than the instilling and imparting of martial, familial, and religious virtue. This explains why reading now, say, the Arthurian Legends one is struck mainly by how unlike novels they are. This is because, moving from feudal to mercantile to capitalist societies, the role of the individual changed. Marxists will argue this is due to material realities, but if the moving force, as per Pareto, is instead the driving sentiments of human life, then artistic direction would be motivated by the same drives which direct power. In other words, as the novel became the primary mode of expression of a world that had placed human agency and choice — the rational consumer, conscience as moral arbiter, perspective as the focal point of vision — at its centre, it was reflecting the relations between man which the organised minority of the time had brought to pass.

The early novels however, despite whatever conservative trappings they may have had, are ultimately a depiction of man striving to negotiate, and later to remove himself from, the old societal ties. The convention of a marriage at the end of a Victorian novel, of the two children and the Newfoundland tumbling over the lawn, gave way almost immediately — indeed the two modes were concurrent — to man, and indeed, woman, attempting to escape the bounds of religion, class, family et al. Here Stendhal stands beside Jane Austen, Dickens beside Flaubert. It is here, perhaps more clearly than anywhere else, we see that when Power decided to dispense with the old ties it did so, and when they finally died they gave way to new ones. The moneyed bourgeois classes, having finally wrested power from the early-modern bureaucracy, had their houses painted, then their horses, then their fruit bowls. Nymphs frolicking in Arcadian groves became naked women picnicking in the public park. Finally perspective gave way to Cubism, Fauvism, Surrealism, and all other forms of abstraction.

It is here, closer to our own times, that this phenomenon is even clearer to see. At the beginning of the USSR, avant-garde art movements were welcomed as a means of revolutionary expression. These elements were then soon purged as bourgeois, reactionary elements, despite being often anti-bourgeois, anti-capitalist, and left-wing. The reason was nothing short of the fact that Power had changed, and the elite having been recycled, it required art to follow suit. And it did. Avant-garde gave way to Socialist-Realism, and the West, in retaliation, began funding Abstract Expressionism, Encounter magazine, and so on1. Were the artistic classes, in both these instances, changing organically in both societies? Was the revolutionary art of the modern west the prime mover of its own aesthetic? Was Socialist-Realism, in these terms, any different? The truth is that the avant-garde died in Russia because they were killed, and the avant-garde in America lived because they were buoyed up.

This may well sound sacrilegious to all those of artistic temperament. I know because I too have come to this by long and reluctant struggles. Yet reluctance is often the final barrier to truth: a bitter pill indeed. Yet we needn’t feel dejected in recognition of this truth. Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel, after all; Raphael the Papal apartments; Holbein the Courts of his day. Art followed power and was alert to the manner in which it desired to speak to itself. Just as Erastianism placed religion beneath politics, so too we must dispense with the idea that the artist sits courted by the muse in solitary reveries, free from all societal ties. If the bohemian stands in a separate class it serves only to prove that society has a use for him, and that use is demarcated and defined by its elite. So, just as the novelist became the expression of the power of bourgeois interests, so it was that they were paid not like their forebear poets and painters by aristocratic patrons, nor even by captains of industry, but by publishers — by moneyed middle-men.

They did so because Power wishes to express itself to itself, but it wishes to do so in a particular way. Various vectors of exchange cross paths here and intermingle, but the crux of the matter is this: art needn’t address a king directly to present the formula of his power; the very means of its presentation, the things a society chooses to depict and how they depict them (this is often the greater indicator) all those things inherent in its composition are themselves a depiction of power’s ability to instruct perception. Art aestheticises Power, makes its political vision a series of objects which leave behind a record not of its military prowess or social achievements primarily, but of its way of seeing.

This needn’t be a ham-fisted political broadcast either. The self-portraits of Rembrandt are as easily a representation of how the individual sees himself through the eyes of a certain mode of power as the landscapes of Poussin are in regarding open space. This is the chief operation of art. The throb in one’s veins standing in the basilica of St Peter’s in Rome, or in audience of Titian’s Perseus and Andromeda, are only one form of its expression.

So it is that when a rival organised minority emerges a rival vision arrives with it. Art begins speaking with a different voice. When that minority seizes the reigns, that vision then ceases to be experimental, radical, avant-garde, and becomes settled, accepted, perhaps even ‘classic’. Sometimes it may address the old subjects in new ways, sometimes it may address fundamentally new ones, but I suggest that when it does the latter it is emblematic of a radical shift of one power to another — a conscious desire to break from one fundamental type of elite to another. For sometimes a new power clothes itself in the trappings of those it has usurped, at others it accentuates its differences.

Art for much of the last century has presented itself, indeed it is, a radical break from previous idioms. No more is this so than in the plastic arts. The Abstract Expressionism of 1950s New York and its various off-shoots within very little time found their chief fruits hung on the walls of executive offices. A movement which embraced pure abstraction and amorphous form had its chief adherents among this class of people, whose job it was to form and shape public opinion by mass communications and information exchange. The ad-man, with his Jackson Pollock or Rothko on the wall behind him, did not lead one to it with the gentle explanation, ‘it means whatever you think it does,’ but with the phrase, ‘let me explain it to you.’

This, of course, by various means has always been the case. Yet, in a time when certain symbols had a common currency, when there was a shared and understood idiom through which power expressed itself and operated, men and women had some anchor from which they could not be entirely coerced — or, in fact, whereby they and Power had some common voice. When that idiom was consciously dispensed with — when the symbol became the amorphous globule — myriad different men arrived to hold the hand of the bemused mass to explain to it what it meant. Of course, quite because it was an amorphous blob, it could mean anything. Power, as expressed through art, had become essentially limitless because what mattered was not the canvas itself, but what the man or the little piece of paper affixed on the wall beside it was saying. It could make you see anything.

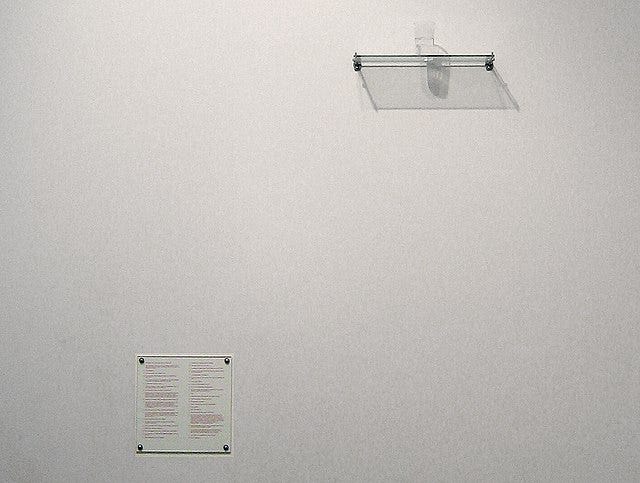

The same thing is true of conceptual art, which, in a recalibration of power, attempted to make of the mass-produced object a new idiom:

All this is to say quite simply, just as politics is returning to a whole host of questions and areas of life, reinvigorating them, taking what was once settled and petrified and making it again up for contention; so art, which has for so long been a stale means for a tired authority to explain rather than allowing us to see, will find potential avenues by which new and contending powers will ignite visions alive and vitalistic. With space for new organised minorities there will increasingly be opportunity for new voices, new forms of human expression. We must not be blind.

For politics is back. Art must, and will, follow.

- See Who Paid the Piper?: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, 2000, Granta Books for a detailed explanation of how American Intelligence Services turned modern intellectual and artistic currents, knowingly and unknowingly, as a means of containment during the Cold War. ↩︎

Amory Crane is Editor-in-Chief at Decadent Serpent. He covers such topics as Art, Literature, and the more broadly Cultural, reporting straight from the chamber of what Shelley once called the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’. You can follow him @LaughingCav1 on X or on Substack. He also writes fiction.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.