Author: Amory Crane

Our first home is dark, like our last. In it we lay, sheltered, comfortable; aware perhaps, in some subtle and intuitive way, and by some primal communication, some commingling of the blood — running from one body to another, the larger to the smaller, decanted from mother to child — of the expectancy, or perhaps the anxiety, surrounding our arrival.

Our second home is the one we remember. From our mothers’s arms we first surveyed the space: shapes, colours; the walls and the furniture; the presence and absence of light; the uses to which all these things are put. Such things, and their relationship to our parents, taught us not in the first instance by rote or prescription, but by observation and mimicry, what a home is; our relationship to which we differentiate from the outside world but which remains, nevertheless, outside our self. Certain actions we then carried with us outside, sometimes altering them subtly, or not so subtly, to delineate between public and private. I am talking here about table manners, or how we shake hands, how we greet strangers and acquaintances. For some others we might make deeper differentiations. Our sense of humour, for instance, may be a negotiation between outside, conditioned by the boundaries of what is permitted by friends, teachers, rivals, girlfriends or boyfriends, and the home, by that which is permitted by our mother or father. We stand then, this figure of mediation, on the verge of the front door, smuggling each time we return to the house a little of the outside in, and each time we leave a little of the inside, out.

This inevitably causes a dissonance. One of the first instances of this of which I recall becoming conscious was that disparity between what I found amusing among the company of my parents and siblings in the walls of my home, and what I laughed at among my group of friends. This usually manifested itself in a minute disembodiment, or perhaps retreat, so that I felt as if I were staring up from the bottom of a deep well at two holes which were the space once left for my eyes. I felt as if I were somehow betraying one group of persons: my family or my friends — perhaps both. Then, after a little thought and further disquiet, I wondered whether I was not in fact betraying myself.

I describe this phenomena not because I think it unique — in fact I believe it to be fundamental and ubiquitous, and perfectly healthy in its way, a right of passage if you will — but precisely because I believe it to be essentially tactile to the thought of today. We know it intuitively, and it goes some little way to account for that general malaise which is ushered in by adolescence. However, there are deeper and yet, at least now, more selective experiences of which we may not normally approach in this manner, but which are nonetheless appreciable by holding in our minds this state of affairs. I am talking now about art.

Permit me then, for a moment at least, to smuggle to the outside world something from within.

One of — or perhaps my first — exposures to art was at the hearth. The reason being my father had at one time come into possession of a fire-screen depicting in reproduction Lord Leighton’s Flaming June. Being at my eye level, for I was only young, I was then able in a way not possible with the pictures hanging higher up on the walls to examine it as if it were one of them. This then became my first real confrontation with art. The result of which is that even after all this time, I return in my mind almost daily to the picture, and others of my childhood and youth, in a manner I do with few others. For the pictures we grow up with are not like those we meet in the gallery. They are in some sense like the coffee-table, the vase, the shoe- or pan-rack, the old leather armchair. That there exists, unlike the shoe-rack, a relationship between what is depicted and what lies outside of the house, or a potential one, is state of being that so mirrors our own that we are alive to the manner by which its place as decoration and its place as a famous or noted piece of art to be adored or studied are in tension. Just think, if this has ever happened to you, of coming across for the first time in a gallery or on someone else’s walls the painting you have in your own drawing room. It is an experience not unlike your parents, or perhaps some member of one set of friends, by the egregious machinations of fate, coming into contact with you among the groupings of another at a particularly compromising moment. Compromising for their perception of you, that is. For while we might be sons or daughters at home we are friends, students, or lovers elsewhere, and often friends, students, lovers of different sorts.

Perhaps to have had this affecting picture wedded to an object of such deliberate purpose — the fire-screen — has made me particularly alert to this peculiar state of affairs. For to watch my father build a fire and place the picture of this beautiful woman in front of it, to see art elided with some utility wielded in his hands, must in some subtle way have conveyed a message. Was Woman fiery? Was she to be shielded, like the fire? Or was she the guard against the fire itself? Indeed, was beauty hot? Was danger alluring? Did it need obscuring by some simulation, some personification? Or did the picture amplify the physical and unique instance of what was in front of me — fire — into unexplored territory? Such paradoxes exist as often beneath the simplest of acts in our homely life as they do in art, and we return to them again and again like a riddle.

I only bring this to your attention to show how art interacts with our early interior lives in a way that has become almost completely absent in those of today’s young. Like the bookshelf, which had once been ubiquitous, the framed picture or, more likely, reproduction — not the family photograph, which is a different phenomenon — has been replaced not because of some anxiety regarding the mass-reproduced as against the authentic artefact, but in favour of the purely mass-produced object, which does not even fein a relationship to an ‘original’. For these objects have, in essence, no original; or no recognisable one. Nor do they address this phenomenon — the environment from which they are born. No, they are framed phrases, such as ‘Home Sweet Home’ or ‘Live Laugh Love’, crude and empty depictions of objects or emotions which somehow detract from those which they purport to represent. They simply regurgitate the crudest aspects of our exterior culture directly into our own homes. Perhaps even more so than the television, perhaps less obviously than the phone.

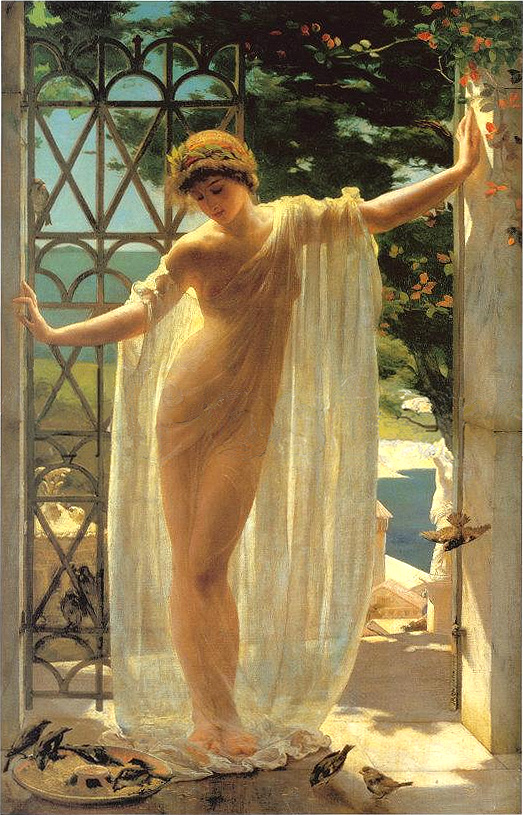

Now, before some psychologist points at my relationship with Flaming June as an example of some unresolved scar or neurosis, let me at least state that it is, first and foremost, an enhancing interaction of life, and whether or no it need be resolved in some way, it adds that which is nevertheless so lacking from contemporary life. It adds, in a word, texture. Let me develop this point further. As I have grown older, and since my father died, I have noted the preponderance of reproductions in my childhood home were of a certain pre-Raphaelite variety. These were not in the weightier, even slightly lascivious manner of Rossetti, but of the second generation, of men such as Weguelin, Waterhouse, and Leighton. These men portrayed Woman, in her demeanour, much like a passing dandelion seed in a languorous breeze; in the kind of mood in which her speech is seemingly always presaged by a longing sigh. She is contemplative, melancholic, but not — at their best — without some sensuous anchor to herself. This latter part is perhaps most notable. For despite the overt sexuality, as in Lesbia or June, there is a kind of languid and thoughtful repose, a waiting not so much for a fixed appointment, but for some obscure consummation, which keeps these women from being entirely dependent on the whims or felicity of a lover, though still far from being overtly assertive. They are then, in some obscure way, Woman groping towards some powerful and sought-after desire, blind to where exactly she must find it, and aware she must not search too explicitly.

All this I have come to conclude by a manner not dissimilar from that as I would deploy to any painting. What differs, however, is that looking back at my earliest experiences of love or infatuation, of that first stirring of sentiments by which we are inducted into life, I am conscious that I was drawn to someone who in the aesthetic qualities I have adumbrated above was not at all dissimilar to these depictions. Indeed, of all the reproductions housed in my childhood home it is Waterhouse’s Windflowers which means the most. It is so precisely that it forms the conduit, the junction at which the home and the outside, childhood and adulthood, my father and myself, my granted family and the desire, however nebulous, to go forth and start my own, all intersect. Alas, I never had the opportunity to ask my father in any detail about his taste in art, let alone his specific interest in these pictures. But in a way I am always, when thinking of them, in conversation with his presence if not his being.

Between the in and the outside then, the past and present, the subject and object in our perceptions, such things become nothing short of a primer to our being, ones we return to periodically throughout our lives. Those experiences and memories which come to settle on the paint are not unlike the annotations accrued over many years in a worn and beloved book, which we come to read with the same avidity as the text. That paintings such as Lesbia, Flaming June, and Windflowers all came to form an unconscious template for the direction and patterns of my desire remains for me the perfect example of how that which tends to us in our most preserved moments is always in danger of being smuggled into the outside world. That we are forever condemned to betray ourselves in just this fashion lends a much needed texture to modern life.

— Amory Crane

Amory Crane is Editor-in-Chief at Decadent Serpent. He covers such topics as Art, Literature, and the more broadly Cultural, reporting straight from the chamber of what Shelley once called the ‘unacknowledged legislators of the world’. You can follow him @LaughingCav1 on X or on Substack. He also writes fiction.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.