Author: Sam Wild

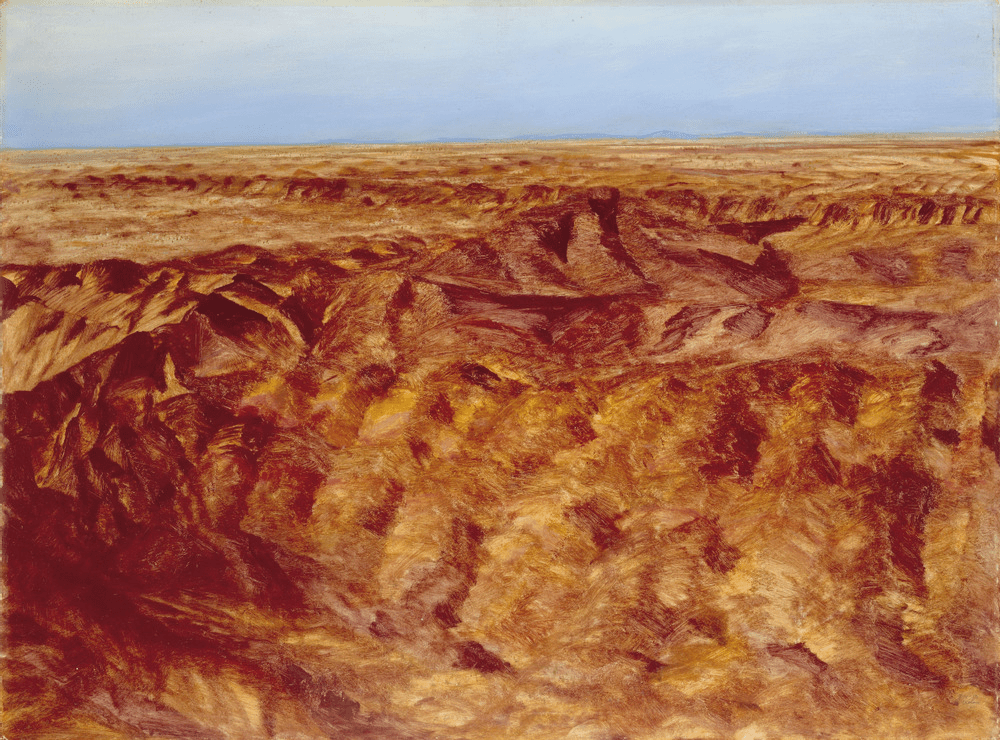

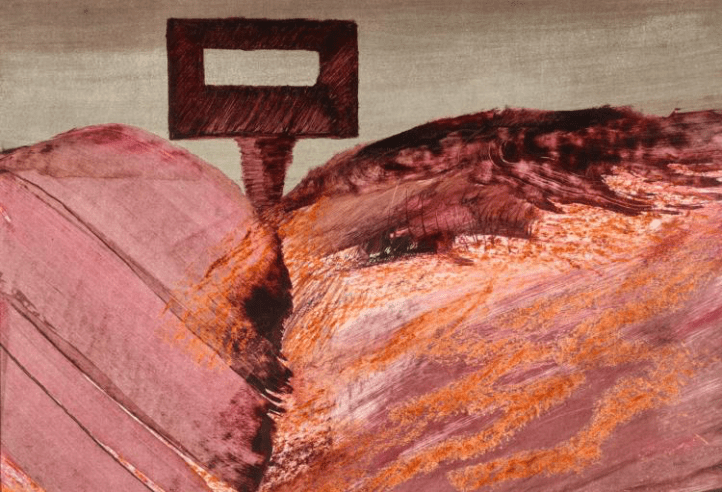

A vast red landscape unfolds before us towards a high skyline. There is nothing here but sand, rock, and sky. Even a cloud is a rare sight. Civilisation hasn’t corrupted the purity of this landscape; it’s too pure, too sanctified in the stark ferocity of its nothingness.

Are we on Mars? Is this a scene from Total Recall? Or Dune? Is this a desert planet? It seemingly has no end and engulfs everything around it. Our points of reference fail to capture the absolute that this landscape presents to us. It’s not interested in making itself understood, if it could be understood. No, this red waste is impervious to civilisation and human culture. The world of men, with its words, tools, and buildings is blown away as the grains of sands are thrashed around by the winds of this indifferent world.

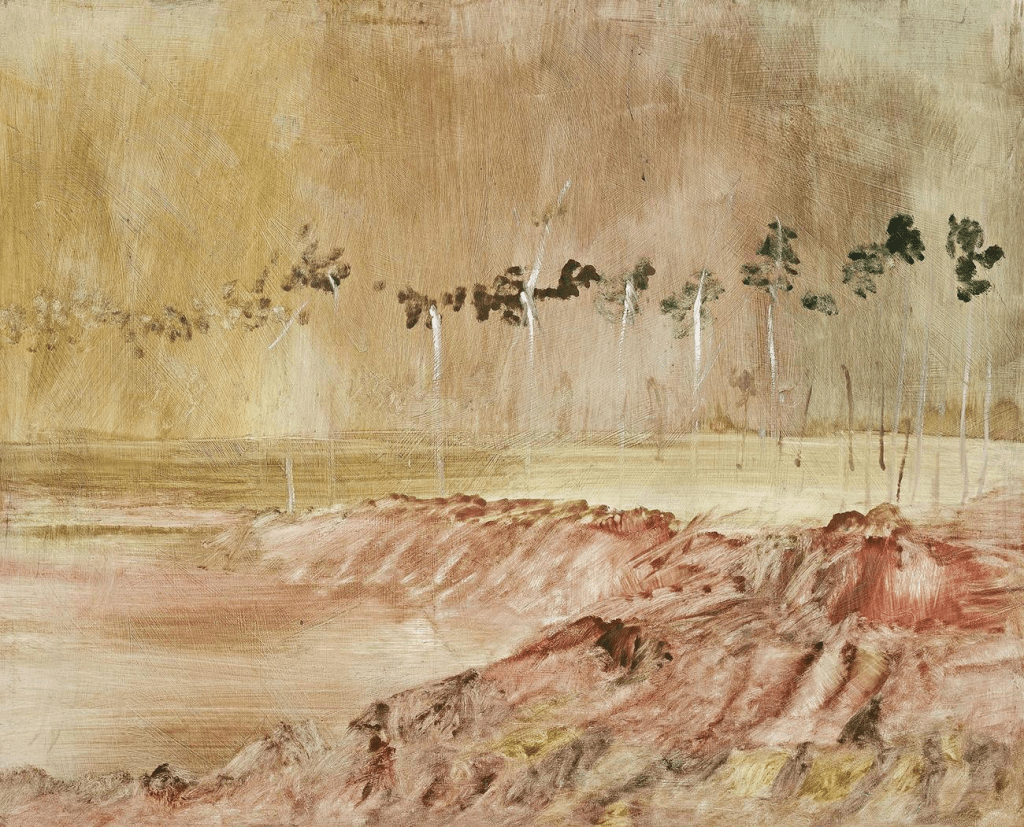

This is the world presented to us by the landscape paintings of the Australian painter Sidney Nolan. His canvases were moulded by this landscape. Rarely taking to them any other colour than red, yellow, and blue, the paintings are purely concerned with the elemental. It is a world of pure colour and form. Not a geometrical form of classical or abstract art but a form moulded by the forces that shape nature itself — earth, wind, and heat. Nolan, with his paint, guides us through these apathetic forces as they erode rock, reflect the baking sun’s relentless light, and as heat cracks the earth. What little life survives out here is no more than bracken and bush. Matchstick-like trees poke out the ground, tiny dry shards of organic life.

Nolan’s technique is one of thin but erratic washes of transparent oil paint that bleed into each other. Sometimes they describe the rock formations of this alien world with seeming verisimilitude, sometimes we become aware of the artist’s sweeping hand as he lays an irregular wash of dark orange here or cerulean blue there. Bodies come and go. Places come in and out of existence. The outback is merely a field where reality comes into being and then dissolves again, it won’t allow anything to last.

Not that it breaks things down like a thunderstorm. It doesn’t attack shape and form head on. It waits you out, just as Nolan’s colour has a subtle and timeless patience. The desert melts you away as the painting’s colours play on your mind.

Nolan made these landscape depictions of the outback in the late 40s and 50s. He had just engaged in a reckless marriage to Cynthia Reed after her sister-in-law, the already married Sunday Reed, had ended a long love affair with him. All three were part of the Heide Circle, a group of artists and writers that wanted to introduce modernism to Australia. The group gathered at an old dairy farm just outside Melbourne bought by Cynthia’s wealthy brother John. Despite the artistic creativity present at Heide, the chaotic love affairs of everyone involved finally reached a breaking point when Nolan married Cynthia.

This wasn’t the only less than pleasant or honourable choice made by Nolan. He deserted from the army during WW2. Whilst granted leave in 1944 he failed to return to the army, and instead used a pseudonym and went to live with the Reed’s at Heide. It was during this time that he saw an exhibition of Ned Kelly’s armour in Melbourne and remembered that his grandfather had been part of the group of police officers that had chased the famous bandit down in 1879. Perhaps his own illegal status led him to take the story of Kelly to heart as from this point he began his famous series of Ned Kelly paintings.

Kelly, the most notorious bandit, or “bushranger”, in Australian history was executed in November 1880. He stole cattle, boxed bare-knuckle, robbed banks, and shot police constables for around ten years until his famous showdown with the constabulary at Glenrowan, where he and his gang fashioned crude metal armour to make themselves bullet proof. A vicious shoot-out occurred and out of all of his gang only Kelly survived. He was hanged shortly after. After the noose was laid across his neck he simply said, “such is life”.

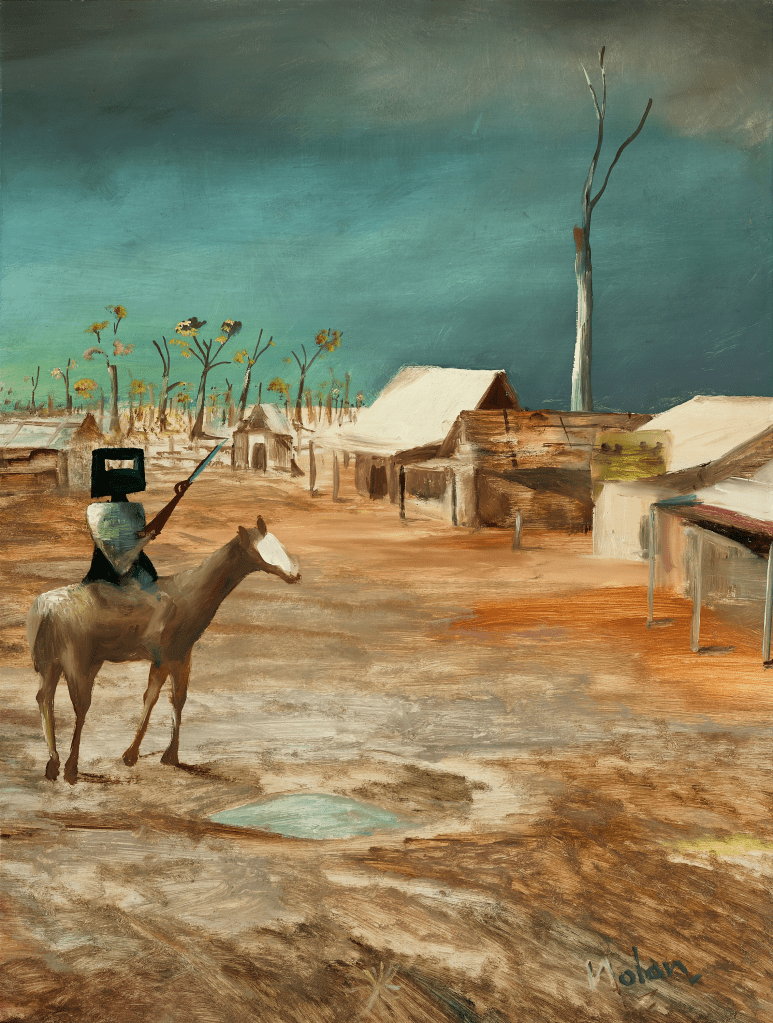

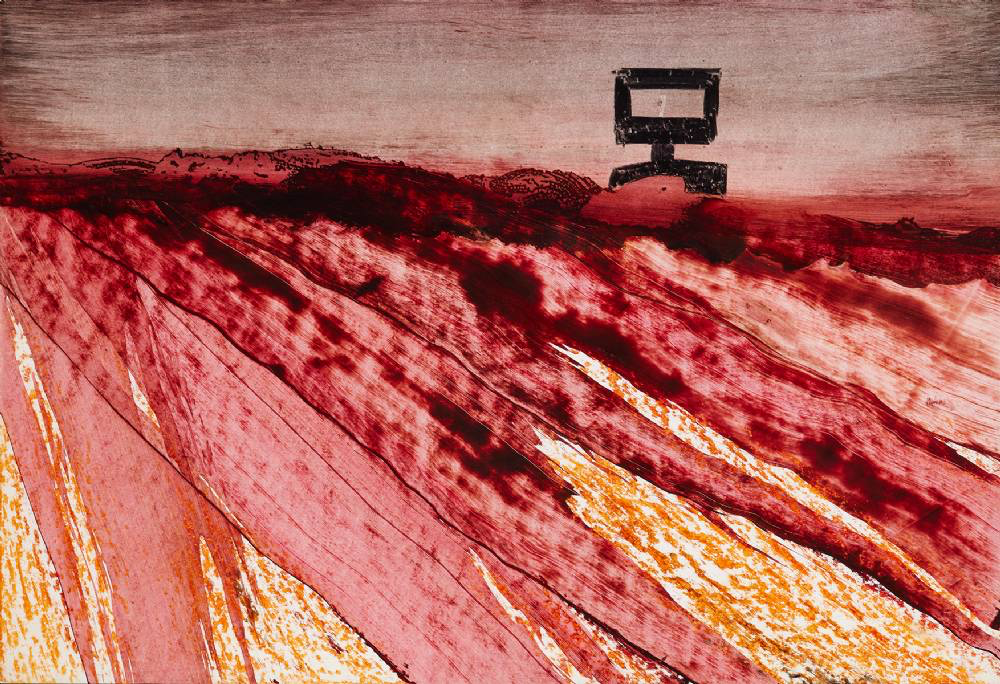

In his painting Nolan represents Kelly as a totemic and mythological figure, represented by his armoured square head. The post-cubist icon roams the outback, on horseback, gun in hand. To start Nolan illustrates points within the Kelly story — the robberies and cop-murders. It is evident that Kelly is the only being in these paintings that can navigate the red land of central Australia. As his paintings progress not only does Nolan depict the biography of the man, his Ned starts to merge with the overpowering force of the Australian desert. The bandit is longer a figure in the landscape — a common theme in Western art — but becomes the landscape. Kelly’s soul becomes an essential part of that mix of transcendent forces and he morphs into a kind of god of the outback.

In this respect, Nolan is following in the footsteps of Van Gogh and Munch in merging the human soul and nature in modernist painting. The formal aspects of painting are utilised as a kind of bridge between our emotive selves and the world. It is a uniquely Northern concern, being present in the art of Friedrich, Turner, and Constable prior to modernism. Nolan transposes it to the antipodal desert but adds the unique theme of a desire for human freedom from a morally puritanical Anglo-Saxon society.

What Nolan’s paintings of Kelly and Australia’s outback open up for us is the possibility that the sublime can be a liberating force. The outback is a place beyond human learning and morality where a man can truly be free. It can’t be put in a jar and tamed. Sure, one part of it can be labeled and examined, but the desert as a whole, as a total experience, cannot. The Australian outback is a kind of Absolute that transcends and destroys us. Indeed, a corollary of all this would be that man can never be truly free, free enough to become a part of the absolute reality of this world, within human civilisation. He requires something more than human, more than moral, that will allow his entry into this state of pure union. Can only men like Kelly do this? If so we don’t have many men like him today, especially in Henry Miller’s “air-conditioned nightmare”.

In a society like contemporary Britain Ned Kelly is evil. But Nolan’s paintings, in their modernistic formal freedom, represent a nature that is indifferent, indeed hostile, to our moralising outlook. The needs of an Anglo-Saxon society, that everyone must earnestly follow the moral law and be “a good person,” are undermined by the possible truth of Nolan’s paintings and the idea of the sublime it presents. This makes Nolan a truly subversive figure within the moral universe of the English-speaking world. As Nolan’s Kelly merges with this reality does it not imply that to become one with the truth and to truly liberate ourselves we have to abandon moral law? Are we then ever caught between the limited world of moral man and the true reality of a sublime world that cares nought for our moral hang-ups? Nolan’s paintings suggest so and not only this, they encourage us to accept this greater reality — the indifferent landscape of the Aussie Sublime.

Sam Wild is an artist working in painting and printmaking exploring vitalism and perennialism in art. You can find his work here.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.