Author: Ryan Shea.

All wrestling fans are doubtless lapsed addicts.

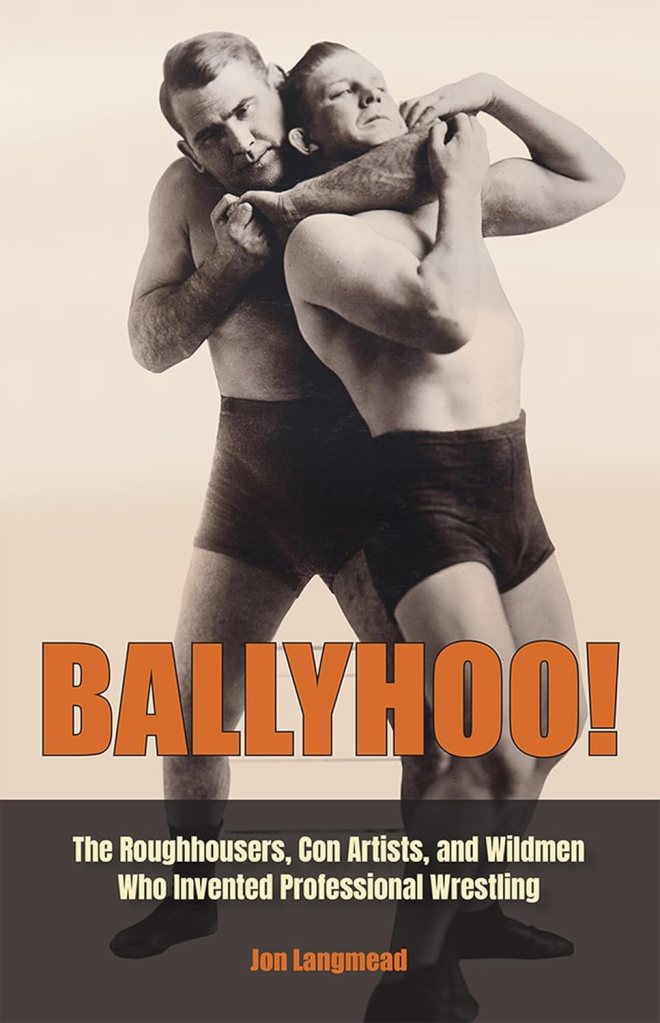

Jon Langmead’s Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling (2024) explores the margins between addiction and artistry in the Art Nouveau origins of professional wrestling. Ballyhoo! takesfor its main protagonist wrestling promoter Jack Curley (born: Jacques Schuel), Langmead’s niche history is an odyssey through the other side of modernity from 1874 to 1941. It is no doubt symbolic of that “old army game” of professional wrestling that all documents relating to Jack Curley’s birth were destroyed in the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Stomping through New York, London, and Vienna, Curley never met a man he did not want to match brawn or brains with—including, while jogging one day, Archduke Franz Ferdinand! While the theorists of the 20th century were distracted trying to construct the political “New Man”, Curley had found his new man in Iowan farm boys like Frank Gotch, Baltic strongmen like George Hackenschmidt, and, christener of the “Irish Whip”, Danno O’Mahoney. Langmead succinctly describes the air which predominated this cosmopolitan milieu of pseudonyms and grapplers as: “…a circus like spectacle that mixed athletics with a meta-type of surrealism.”

Sport or farce? Langmead’s Ballyhoo! directly demolishes the cultural presumption that professional wrestling was a sort of “pariah sport” throughout the 20th century. Never ostracized, besides when his pockets were empty, Jack Curley schmoozed with British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, American orator William Jennings Bryan, and philosophers like M. M. Mangasarian. On certain occasions, Curley would have been within earshot of F. Scott Fitzgerald in Great Necks, New York, or T. S. Eliot in Boston and London. Rather than reviled, Curley’s czar status within wrestling and boxing represented an interstitial world of sports, entertainment, and social influence. Politicians and gangsters sat side by side in smoky dens, or hastily constructed wooden arenas, that Curley booked men to brawl in for hours. Figures such as the platonic mobster Arnold Rothstein (model for Fitzgerald’s “gambler” Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby) were commonplace among the cheers, jeers, and overall tension in the stands. As wrestling was not officially organized in New York until 1920, Curley’s shows often ran the risk of being shut down by state militia due to fears that such “intensity” would inspire a riot. It was high-stakes in the ring and in the ticket booth. Curley and his fellow promoters often had to rely on word of mouth, backroom deals, and unofficial cartels to guarantee the jaw-dropping profits they could pull in. Curley believed that, above all else, that wrestling was made to be entertaining.

Though he never draws the comparison, Langmead depicts the American-European world of fin de siècle professional wrestling as the equivalent of the Japanese “Floating World” or Ukiyo. Wherever they could be showcased, wrestling bouts were a realm of high drama and competitive pleasure that lit up the night like a fusion of gambling and kabuki. The morality of wrestlers and spectators was annulled for as long as two men grappled in the ring. Matches could last for a few minutes or drag on for hours until 2:30 AM. It was common for matches with undetermined outcomes to be demeaned as fake, while predetermined matches were upheld as legitimate contests. Wrestling lingo was colorful and all-encompassing: “Shoots” were the legitimate bouts, while “Works” were matches where the conspiring opponents pulled punches. Wrestler Toots Mondt famously had to circulate coded letters designating fellow wrestlers as “O.K.” or “Not O.K.” depending on their willingness to wrestle along a script. Eventually, the “Works” (O.K.) won out and the “Shoots” (Not O.K.) went extinct. Professional wrestling was founded on a basis of trust between competitors that will shock the modern reader. Wrestler Lou Thesz once implied a true wrestler would rather die than let the “trade secrets” of wrestling be known to the public. Etymological origins in carnival sideshows and confidence men, Langmead describes the whole liminal culture as a “conspiracy inside a conspiracy.”

Though bursting with a variety of Mucha-esque anecdotes, Langmead does not neglect the historical or theatrical dimensions of wrestling. American-European ring wrestling receives an extensive genealogy in Ballyhoo! Langmead chronicles modern professional wrestling as the scion of several fighting styles: the Irish “Collar-and-Elbow”, the English “Catch-as-you-Can” style, the informal “Rough and Tumble” of the American South, then the civilized “Greco-Roman” of the wider European model. Theatrics were slowly added as sport became spectacle: wrestlers attributed their losses to false injuries to set up rematches, bladders filled with red ink were hidden in the mouth to simulate bloodshed, and referees slapped the ring mat to alert the audience to pinfalls. Promoters like Samuel Rachmann in New York merged the brawling with the costumed sensibilities of the Ziegfeld Follies in 1915. Masked burlesque dancers of the Follies, such as Le Domino Rogue (Daisy Ann Peterkin), inspired the development of masked wrestlers and Olympian melodrama in the squared circle (ring). It was once thought professional wrestling would not survive the 1950s, but wrestling appears to be a perennial symptom of, or a lapse in, modernity. Four-time World Heavyweight Wrestling Champion, Ed “Strangler” Lewis, once dictated about his chosen profession in rather literary terms: “Human memory is short and the routine is so simple that it is always new.”

Langmead’s conclusion, no doubt shocking to both the advocates and doubters, is that professional wrestling was always understood as somewhat fake by the public. It was fake in the sense of myth. Though cited, Jon Langmead does not need to be Roland Barthes or Jack Kerouac to initiate the reader into the mystery cult of wrestling. Wrestling was (and should be) the same as American Heavyweight Champion Evan Lewis is described: “Rough, unapologetic, and awe-inspiring.”

Ballyhoo! is red meat for both the suckers and the scoffers.

Ryan Shea is a New England Tom of Bedlam. His writing focuses on the antipodes of literary culture and the Internet. His work has previously appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Atlas Obscura, and in French translation in the review Librarioli. He is currently a columnist for the music site Invisible Oranges. He looks forward to each project that requires one thousand and one nights to complete. His meandering cross sections can be found at Zoflyoa on Instagram.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.