Author: Adam Gorecki

There’s no easy way of understanding the world we live in without stories. We carry them with us, we share them with others and if we’re wise enough, we use these stories as a navigation for our own lives. Our brains are quite literally wired to translate our daily experiences into tales, distinguishing what our place is in this crazy narrative called life. It means that we’re given the choice to carefully rationalise what’s been placed in front of us or to dissolve into our own disillusioned and fanatical realities. That’s the choice we wake up to every morning. Our fascination with storytelling comes from its ability to reignite our imagination which can reclaim our own childlike wonder. For brief moments, an entrancing and encapsulating story can allow us all to become children again. Our perceptions are what entitle us to be unique, creative, and to physically become an acute antenna for inspiration. Furthermore, it’s this very inspiration that has birthed an incredible selection of albums that sit on our record shelves today.

Somewhere between the 60’s and the 80’s, albums became a tool for utilising a set of tracks to hold a larger meaning together than when apart. We see early signs of this prior to the 1960s, with works such as Woodie Guthrie’s ‘Dust Bowl Ballads’ from 1940 which articulates the American struggle of The Great Depression, or Frank Sinatra’s ‘In The Wee Small Hours’ from 1955. Throughout the 1960s, The Beach Boys’ ‘Pet Sounds’ and The Beatles’ ‘Sergeant Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band’ introduced heavy thematic and emotional consistencies and became a steady starting point, but they still lacked substantial, overarching narratives. It was safe to say, however, that the seed had been planted from this point onward. Artists became more and more capable of indulging in their own creative spontaneities and pushing themselves to combine excellent music with immersive storytelling. The outbreak of this revolution can be found at the heart of Rock Opera.

The genres of Rock and Opera both shared a grand and glorified command of the stage throughout their listening experiences. Rock Opera, however, merged the heavy, flamboyant and innovative presence of rock with the continuing narrative and spectacular musical motifs of an Opera. It gave artists permission to escort us through the dramatic highs and lows of theatrical tragedy and heroism all within the walls of a 12-inch LP. It gave each individual track more substance and meaning, and a contribution towards a higher and more daring overall project. At the peak of musical innovation in the 70s, a compelling narrative justified and enhanced the obscure and experimental listening experience, making albums all the more engaging. Narratives typically resembled the story of a young underdog embarking on a traitorous journey through life, often a reflection of the artists themselves.

S.F Sorrow- The Pretty Things

The dawn of Rock Opera was founded at the latter end of the 1960s, with the project ‘S.F Sorrow’ by The Pretty Things. From the outset, the album takes us through the birth, life and death of the character Sebastian F Sorrow.

‘S.F Sorrow is born!’ is the repeated refrain in the opening track, accompanied by playful claps and royal trumpets as an optimistic cheer for new life. Each song stands as a testament towards the trials and tribulations we endure throughout our adolescence, adulthood and impending demise. Moreover, the technical musical structure of each track articulates the emotional state of each life period. Tracks such as ‘Bracelets of Fingers’ show our young character exploring the concepts of love, dreams and optimism. There’s an immersive psychedelic presence in this track particularly, enhanced by the use of a Sitar and flanging/phasing effects, which sedate us into a dream-like trance of childhood wonder. As the album grows into itself, the tone continuously shifts. Mellotrons and militarised marching snares accompany SF Sorrow into the depths of World War 1 with tracks such as Private Sorrow and Balloon Burning. Although there’s no explicit death of Sorrow on the album, we do witness the character embrace a spiritual demise. With the loss of his own identity, heart and soul, we’re left questioning if SF Sorrow’s fate is perhaps worse than death itself, being referred to as ‘The loneliest person in the world’.

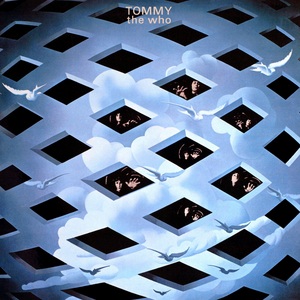

Tommy – The Who

I’ve covered music’s morbid portrayal of post-adolescent life in my previous article, it’s worth bearing in mind that it may be an accurate betrayal for people whose child-like optimism had been crushed by traumatic wars, addiction or entrapping full-time jobs. Life throws curveballs, and as I said about our brains perceiving life as stories, it’s up to us as to how these stories are navigated and how they will end. It takes me onto our next chapter in conceptual Rock Opera, an extravagant and grandiose story of a young boy who is dumb, deaf and blind. The Who released their critically acclaimed album, ‘Tommy’, in 1969 and is known to be one of the most profound and impressive conceptual albums of all time. The lyrics, instrumental and overall message of this project is something that is very carefully depicted and executed every step of the way, which makes it all the more impressive.

The premise of the story surrounds this young boy witnessing his parents commit an act of adultery that results in murder, causing him to retreat into an internal dream world of self-suppression and blindness. They say ‘You didn’t hear it, you didn’t see it, you won’t say nothing to no one.’ After undergoing his own sexual and domestic abuse whilst in this state, Tommy goes on to become a world-renowned pinball champion and prophet who attracts devoted followers. As he regains his senses, he discovers a deep and spiritual sense of self-awareness and a higher understanding of life. The music presents itself as a mystical vibration that serves beyond physical reality itself and reflects the ecstasy of enlightenment. However, his demise undoubtedly occurs through his uncle commercialising his teachings, leaving Tommy alone and afraid once more.

Throughout the album, we repeatedly come across operatic vocal motifs which serve as a desperately suffocating cry for help from Tommy. Keith Moon’s drumming (as always), spirals itself into a ruthless bedlam throughout the entire record and forces us to feel the multitude of senses that are deprived from Tommy. More impressively, the album demonstrates itself in the form of three distinctive acts, much like a formal narrative. The song, ‘Smash The Mirror’, in particular, is a dramatic and immersive turning point for the record that steers our protagonist down a new path.

The album reflects on the internal suffering and suppression of childhood trauma as well as the commercialisation of spiritual prophecies. Pete Townsend took a lot of his inspiration from spiritual leader, Meher Baba, who preached silence, inner wisdom and self-purification. Along with his interest in sense-deprived children and his own childhood traumas, the project serves as Townsend’s own search for identity; a similar theme throughout 1970’s Rock Opera. In 1979, Roger Waters would go on to use this as inspiration for Pink Floyd’s magnum opus, ‘The Wall’; a self-induced Opera based around the upbringing of Waters, which goes on to represent the political and thematic structure of modern-day society. Both records went to be turned into successful movies, translating their musical narrative into a full-scale, cinematic production.

Evidently, the phenomenon of Rock Opera in the 1970s served as a therapeutic mouthpiece for artists to dissect and articulate the journeys of their early lives. Of course, nearly every project an artist produces is in some form a reflection of their internalised selves. But throughout this particular period, musicians gained an artistic license to overly romanticise, conceptualise and dramatize their own personas for the sake of a compelling narrative to tell throughout their projects. However, there was one who exceeded the boundaries of their own creative outlet, taking their inner quirkiness and twisting it into a conceptualised character who embarks on an epic quest to save Earth from a Five-Year apocalypse. You’ve guessed it.

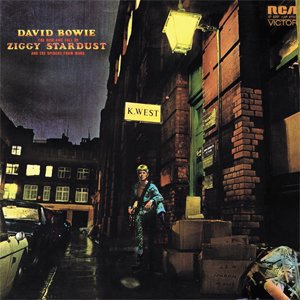

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars – David Bowie

David Bowie gave breath to the character Ziggy Stardust in his most renowned album, ‘The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars’, a glam rock extravaganza that personifies the glamorising pinnacle of Bowie’s fame into a flamboyant, yet tragically doomed hero. Funnily enough, the title takes its inspiration from the opera ‘Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny)’. It continues Bowie’s fascination around space which has been seen in previous singles such as Life on Mars and most famously, Space Oddity. However, this time David was the man falling from the stars; courageous to save us all, but fearful for the consequences. Bowie is one of the few artists whose vocals stand out like an intensely burning star. It’s blazing, florescent and vastly intense. However, as bright as they are, the burning of a star will be one that causes excruciating pain… and inevitably, the star will die. The concept of Ziggy Stardust depicts the tale of a bisexual rockstar who falls from the skies, pledging to save the world from an apocalypse. In the end, the total iridescence of Ziggy’s stardom and spotlight burns him alive into a ‘Rock N Roll Suicide’. Like all of our reviewed projects so far, the album stands as a self-reference to Bowie’s fame and talent feeling like a form of alienation that has the potential to provide goodwill to the world, but there plays a great risk in burning up in the ego that arises from it.

There are hundreds of records that personify the struggles of fame not being all it’s cracked up to be, but the extensive creativity, ingenious lyrics and outstanding theatrical display of music are what defines this album as an all-time classic. There’s a perfect contrast of big bold messages and intrinsic, cryptic lyricism that dances its way across the project. Moreover, the song, ‘Five Years’, goes down in my opinion as one of the most profound and eccentric introductory songs to an album of all time. There’s a gradual string crescendo that builds with humanised lyrics of nostalgia, reminiscence, observations of society and an acceptance of doom. It explodes into a belting weep from Bowie which sends us through the flaming inferno of his mind with the exclamation of how his ‘brain hurts a lot!’. This belting cry from Bowie continuously appears across the project, mimicking the agony behind a tormented artist. It carries with it, the emotional rollercoaster of an opera which continues throughout the loose narrative of glamour and tragedy.

Bowie also conceptualises a band, The Spiders from Mars, which in real life was formed by Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Mick Woodmansey. Unified support for our protagonist, whose musical bond collapses through Ziggy ‘making love with his ego’ throughout the track ‘Ziggy Stardust’ which concludes with a breakup of the group. Bookending ‘Five Years’, is the final track of the project, ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide’, a sentimental final look back at this character. Exiting the album, the story and the life of Ziggy Stardust, we see Ziggy make amends with the pure feelings of peace and love, in exchange for his own life. Bowie would often perform this song last on his tour for the album, alongside The Spiders from Mars. On the final show of the tour at The Hammersmith Odeon, Bowie stated

“Of all of the shows on this tour, this particular show will remain with us the longest because not only is it–not only is it the last show of the tour, but it’s the last show that we’ll ever do. Thank you.”

Staying true to the character, and himself, Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars were never seen again after these words were spoken.

The conceptual dissection of space has been a favourable topic for artists to explore because it has always been our reality’s closest reach to the fanatical. The day-to-day lives that we live carry so much certainty and predictability, that the idea of something deviously dwelling above us becomes all the more possible when it can lurk within the depths of space.

‘No one would have believed, in the last years of the nineteenth century, that human affairs were being watched from the timeless worlds of space. No one could have dreamed that we were being scrutinised as someone with a microscope studies creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. Few men even considered the possibility of life on other planets. And yet, across the gulf of space, minds immeasurably superior to ours regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly, and surely, they drew their plans against us…’ – Richard Burton as The Journalist in Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of The Worlds.

Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of The Worlds

The prospect of a hostile alien invasion was unheard of when H.G Well’s ‘The War of The Worlds’ started to appear on bookshelves in 1898. The disturbing depiction of human vulnerability from unknown colonisers was as unsettling as it was intriguing to readers. The concept triggered an explosive kickstart for science fiction; inspiring radio shows, films and eventually, a concept album.

Jeff Wayne was far from being a household name at the time of embarking on this daring and adventurous project. However, his gamble on producing the 1978 all-time classic resulted in creating one of the most explosive and revolutionising listening experiences of the 20th century. Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of The Worlds undertook the plot and narration of the iconic storyline and regenerated it into a theatrical audio adventure featuring a wide array of experimental musical production methods. The album went on to become 9x platinum, spending 339 weeks in the charts and directly inspired a stage show, video game and live experience in London (which I visited last week). It included narration from the late great Richard Burton, Justin Hayward from Moody Blues as lead singer and took inspiration from nearly every other album mentioned in this article as well as Rick Wakeman’s ‘The Journey to The Centre of The Earth’.

‘I envisaged my version of War of the Worlds as an opera: story, leitmotifs, musical phrases, sounds and compositions that relate to the whole. I handed my scribbles to my father’s wife, Doreen, and then started composing the score for the album while she wrote a script.’ [1]

The musical retelling of this story allowed for an expansive range of experimental techniques to uniquely tell this tale in a more encapsulating fashion. The album carries itself as an authentic and emotive opera, with character dialogue spread throughout the story. Featured musicians were given scripts and an overview of the characters that they would be playing. The listening experience is intended to dramatically carry you through the events of war with a sonic charge. The album, overall, was strategically produced in three layers; rhythm, synthesisers and strings. It was crucial for these elements to vary depending on whether they represented the Human or Martian side of the story.

The project’s overall rhythm maintains a disco-like feel. It gravitates between this militarised, mechanical percussion which then melts into a more fluid and softer groove which replicates the invasive clash between alien and man. Complex drum signatures and evolving rhythms were purposefully placed to unfold an unpredictable adventure from the outset.

Wayne asked composer, Ken Freeman, to prioritise unearthly sounds for the project; more specifically, he needed them to resemble the Martians and their machinery. In doing so, the pair indulged themselves in creating spontaneous recording strategies to achieve this goal. Ken played the flute, whistle, pipe, drums and horn as well as utilising his wide collection of synthesisers. Varying from an Odyssey MKI, Mini Moog and a Yamaha CS80. The iconic “OOHLAH!” sound that the Martians make throughout the project was inspired by HG Well’s original onomatopoeic term for the Martian cry ‘Aloo’. Reversing the word, the phrase was spoken by the voice of Jo Partridge into a voice box and was distorted through synthesizers. Moreover, the synths were responsible for the sounds of the Martian cylinders crashing on Horsell Common in track 2, however, Wayne wanted a more jarring sound for the twist of the cap. As a solution, the pair scraped two saucepans together and slowed the tape down to create a rustic effect. As well as this, for the heat ray theme on Horsell Common, guitar strings were all turned to the same notes for a fuzzier sound. His layering of synths created a rich, sweeping backdrop that replicated an orchestra but with an unnatural quality. Freeman’s creative instinct inevitably blended the worlds of classical composition, progressive rock, and electronic music which sonically represented a war between musical worlds.

My honourable mention for this incredible project is Forever Autumn, track 4. The song is a voyage towards love and sentiment within a city plagued with destruction and hopelessness. With hardly a mention of the world apocalypse, Richard Burton narrates our protagonist’s quest to retrieve his fiancé throughout a devastated London. There’s something about the adventurous and optimistic flutes and the sudden high-rhythmic drums that sparks a second wind of fearlessness and determination for the listener. The lyrics carry a deep weight of love and purpose and a great deal of reminiscence for simpler times before the apocalypse. “Because you’re not here” is the running motif that reminds us of heart-felt absence, sung by Justin Hayward. Interrupted by another unearthly “OOHLAH!”, our nostalgic love-trance is broken as we awaken to the reality that we are still at war with the Martians and hear them appearing over Big Ben.

Unlike Ziggy Stardust, Tommy and S.F Sorrow, War of The Worlds is a majorly collaborative project. The priority was to audibly tell a story that could sonically throw you headfirst into the chaos of world annihilation. For this to be the case, it required the merging of multiple genres, orchestras, vocals, and musical components as well as major funding from CBS and the entirety of Jeff Wayne’s life savings in order to create this unique experience. Furthermore, the incorporation of sound effects, narrations, experimental sounds, authentic storytelling and compelling art illustrations determines that this was a great bit more than just another concept album. The passion project stands as a rhythmic juggernaut that towers over the concept of concepts, much like the Martian tripods. It brings the elements of excitement and enthusiasm to a project, one that encourages you to sit up and engage with the works, rather than to sit back and indulge. Whether you appreciate the musical pieces or not, I think the intricate attention to detail that comes with fabricating a project of this scale is applaudable. I love it because listening to it feels like a movie, an ultimate example of storytelling and the perfect example of a conceptual album that carries its weight in the name.

Conclusion

With a concept album, there’s a suggestion that the artist deserves more of your attention than typically anticipated. The intention isn’t necessarily to soothe your ears or to push you to dance. It may not be to make you laugh, cry or even think. It’s to construct an overarching narrative for you to exist in for a particular amount of time. It’s a bold and adventurous alternative to reading a book or watching a film. To define is to limit. The story is there to interpret, reconceptualise and most importantly, to inspire. The important factor is that the artist has temporarily created a new and exciting world for you to explore. Especially as adults, it’s incredibly important to take every opportunity you can to indulge yourself in creative methods of storytelling. Imagination can be a scarce resource as life evolves around you, but it is art and stories that can reconnect you to your ‘three-year-old self’, should you allow it to.

It’s what makes conceptual projects very exciting. Because ultimately as the listener, we get to decide what the concept truly means. We get to decide what we take from it, and we’re encouraged to share with others where we agreed and where we differed with our listening experience. It’s why people love art galleries, clever films and mystical novels. There’s always something fun to discover and learn from the ideas of others.

What I discussed in this article was the beaming sunrise of conceptual album production. I intend to further explore the complexities and genre-bending boundaries that are broken down in the name of conceptual projects in future articles. Because as always, we are always only ever at the beginning.

[1] Jeff Wayne – The Guardian 2014

Adam is a London-based writer, maker, and photographer with a broad love for anything that catches his curiosity, particularly music. Graduating with a Level 4 Diploma in Copywriting from The College of Media and Publishing, he sees music as a complex social study and is fascinated by how brilliant ideas can be brought to life. He has a critical eye for great storytelling and thrives in exploring the philosophical side behind an artist’s intentions and what can ignite a spark that lasts for generations.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.