Author: Giulia Prodiguerra

A Dive into the Use of Diegetic Music and the Aesthetic of the Fallout Franchise

*DISCLAIMER: ARTICLE CONTAINS POTENTIAL SPOILERS FOR THE FALLOUT FRANCHISE*

When we think about nuclear fallout and radioactive wasteland, boppy 50s music and friendly mascots are certainly not the first things that come to your mind. But in the Fallout franchise, they are far more common than you would imagine. Considered the spiritual successor of Wasteland (1988) Fallout is living a second golden age, with the 2024 Amazon series breathing new life into it and renewing interest in the franchise created by Tim Cain and Leonard Boyarsky. One of Fallout’s most prominent and recognisable characteristics is the aesthetic, a mixture of pulp, atompunk and glossy 1950s American advertisement.

In this article, I will explore how this aesthetic, combined with a masterful music choice, heavily contributed to the cultural phenomenon of Fallout, and how it managed to encapsulate several cultural and historical undercurrents and make them their own inside the game space.

THE TIMELINE

To understand those influences, we’re going to have a little dive into the development and the history of the franchise.

The seed of the Fallout series was planted with Wasteland, developed by Interplay Production and released in 1988. Coming at the end of the Cold War (the Berlin Wall would fall the following year) the game was set to explore a post-apocalyptic America destroyed by a nuclear holocaust that happened in 1998. However, the writers would have grown up in the midst of the Cold War between the 60s and the 80s, so it’s not surprising that there is an undercurrent of pure, constant fear for the silent threat of global conflict, as the world was still reeling from the horrors of World War II. The influence of the Cold War across media has been expectedly prominent, allowing authors to process an extremely complex and lengthy historical phase through the lens of cinema, books and comics. Cloak and dagger stories have been a substantial part of popular culture during the Cold War in both East and West, showing how polarised and tense the global situation was. Dr Strangelove, Damnation Alley, The Kremlin Letter and Firefox are just a few of the many examples of media produced during this period, and the influence of the Cold War can be detected across the 007 franchise too.

But back to our main protagonist Fallout. At the time of the release of Wasteland, Interplay Production was not a publisher, and co-opted Electronic Arts for the game distribution. However, this meant that once Brian Fargo, Interplay’s founder, wanted to continue using the Wasteland intellectual property, the rights couldn’t be negotiated back from Electronic Arts. Fargo and his team chose to start from scratch, salvaging the positive aspects of Wasteland and developing a new game around it. The process took around ten years, and the first instalment of the Fallout franchise was released in 1997.

The first instalment takes place in 2161, in a post-apocalyptic Southern California. To survive the blasted wasteland, inhospitable and populated with mutated creatures, many people live in underground bunkers known as Vaults, built by the Vault Tech corporation. The series then progresses further in the future, with the latest title Fallout 4 set in 2287 (whereas the TV series takes place in 2296).

The events of Fallout take place in an alternate timeline from ours, a uchronia where the main split from our reality starts in 1969: the USA of Fallout split into 13 commonwealths instead of the 50 states we know. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that on this exact year in our own timeline, on October 10, 1969, President Richard Nixon ordered a squadron of 18 B-52s loaded with nuclear weapons to race to the border of Soviet airspace in order to convince the Soviet Union that he was capable of anything to end the Vietnam War.

From that divergence, the technological run amps up, in a realistic concept of Cold War silent conflict. In 2077, after decades of escalation and technological development, on the 23rd of October, the Great War begins. Uchronias are a great literary device to “experiment” with what could potentially happen if something, sometimes the smallest thing would have been different. Other examples of uchronia in literature are The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick and The Plot Against America by Philip Roth.

As the franchise grew, its aesthetic became more and more solid and immediately identifiable, with a specific 50s pulp flavour that made it instantly recognisable. But how did this happen?

CULTURAL INFLUENCES AND REFERENCES

My idea is to explore more of the world and more of the ethics of a post-nuclear world, not to make a better plasma gun.

Tim Cain

The final creative result, a dark, bitterly ironic retro-futuristic world, is down to a combination of factors and influences, some more planned out than others.

Fallout is an open-world game and has ample variety regarding your choices, as each one influences your own personal story, your allies and even the final outcome. It sets out to explore not only how society and politics would behave in this alternate timeline, but also the singular individual, and it’s undeniable that the levity brought in by the irony and the fun part truly manages to balance this. In Fallout 3, for example, you can decide to blow up Megaton, one of the first cities you can encounter at the very start of the game, built around a dormant nuclear warhead (a small trivia: this was changed in the Japanese version). Of course, not all choices are as impactful as this one, but you will find yourself questioning your own morality at times. Therefore, some occasional levity is more than welcome. Fallout started integrating pop culture references in Fallout 2, with the breaking of the fourth wall and making references to the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. This progressed with the 3rd instalment with hidden achievements (famous the one referencing Indiana Jones one where you can find a skeleton hiding in a fridge, in a failed attempt to survive the nuclear blast).

The aesthetic is in large part a future inspired by what people in the 50s thought it would be: dominant art deco, Googie architecture with bold, smooth lines and geometries, and of course Raygun Gothic (think also The Jetsons).

Glass dome houses, hovering trains, solar-powered cars, bulky computers and robots. Clunky, friendly technology at the service of man, who can now relax and enjoy the family life while the technology does the hard job for him. The main robot helpers that you can encounter across the game maintain the same style or spheres and vacuum tubes: the friendlier ones are called Mr Handy (for the routine house maintenance, but would also pack a punch when required) while the combat robots are called Mr Gutsy.

The influence of the Atomic Age, as one would expect, is heavy too. Also known as the Atomic Era, its beginning is conventionally marked with the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, called the Gadget, at the Trinity test in New Mexico on the 16th of July 1945 during World War II. Combined with the influence of the Space Age, which started with the launch of Sputnik I in 1957, the visual part of these eras encapsulated the constant paradox of nuclear energy. While holding vast promises of clean, advanced solutions for an increasingly complex world (with the added competition of the space race), nuclear energy cannot be untangled from the threat of destruction it intrinsically possesses. And this is the crux of the matter that carries through the whole Fallout series: same as the Cold War, the world seems destined to be eternally polarised.

To address the concerns regarding the safety of nuclear energy, the Atomic Age design attempted to make science more visible and accessible to mainstream culture, with atom-shaped lighting fixtures and furniture, a combination of different geometrical shapes such as spheres and hexagons, along with stars and galaxy motifs. The Chemosphere house, designed by John Lautner in 1960 and situated in the Hollywood Hills, California, is the most iconic example of Atomic Age architecture, the same one that inspired such a vast part of the golden era of science fiction.

To quote Tim Cain again: “Seriously, the artists just thought that 50’s tech looked cool. So they set out to make a future science that looked like what the Golden Era of science fiction thought that future science would look like (if you can follow that sentence). Vacuum tubes, ray guns, mutants, the whole works. And I think they succeeded quite well.”

The up-and-coming American man of tomorrow is represented by the Pip Boy, a jolly fellow that guides you through the different skills and is the recurrent mascot of the Vault-Tech corporation. Other influences cited by the developers stem from movies like Forbidden Planet (1956), Star Wars (1977), Mad Max (1979), and Brazil (1985).

THE MUSIC

“Game spaces evoke narratives because the player is making sense of them in order to engage with them”

Michael Nitsche

We reach one of the other fundamental components of the franchise: the music. “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire” by the Ink Spots and the “Country Roads” rendition for the Fallout 76 trailer have become recurrent earworms even to people not familiar with the game.

Tracks vary from Glenn Miller, Buddy Holly, and Nat King Cole, to then include the likes of the Platters, Johnny Cash, Perry Como and Ella Fitzgerald, encompassing jazz, swing, blues, country, and bluegrass.

Inon Zur composed the score for Fallout 3, considered one of the most emblematic of the series, and aimed to balance traditional American music such as blues and folk with the powerful cadence of military music. The goal was to showcase the American way of life before the nuclear holocaust, while simultaneously showing the military and technological advancement.

The tracks varied from droning, dark ambient (“Radiation Storm”, “Underground Troubles”) to tribal percussion (“Moribund World”, “City of Lost Angels”) to contrast the choice between “the remains of a dead civilization and a return to primal brutality.” But the soundtrack is also combined with diegetic music spanning from the 30s to the 60s. What is diegetic music? It means music playing inside the videogame environment, not as a soundtrack, but as an integral part of the world, meaning characters are listening to it in their own reality. The music plays via the PIP Boy, a wearable computer that the main character wears on their wrist, and which also conveniently includes a radio. Like the rest of the technology, it’s quite clunky, haphazardly holding together.

The radio also allows you to tune in on other frequencies and listen to specific broadcasts, which in turn add to the lore of the game.

Special mention goes to Fallout: New Vegas, a spin-off of the franchise released in 2010. Set in 2228, instead of a vault dweller, the protagonist is a courier who survives an assassination attempt and finds themselves tangled in a turf war between different factions. One of these factions, called the Kings, worships Elvis. Elvis is never directly nominated with his name and is just referred to as The King. Interestingly, the Kings were born because they found an abandoned building with lots of Elvis pictures, assumed he must have been a sort of god, and started worshipping him and dressing like him. Perhaps a reflection of how we turn to makeshift idols to guide us through the darkest of times.

Also, this brought in even more of the 50s and 60s music influence, while Inur Zur added country and bluegrass to reflect the setting of New Vegas.

It’s interesting to notice how the fear and hope for the upcoming atomic age are also directly reflected in several songs spanning across different decades. Let’s see some examples:

Uranium Fever

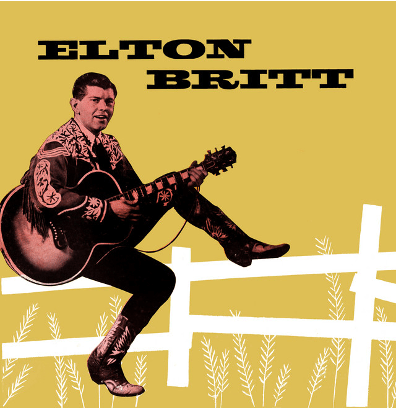

Written and performed by Elton Britt and released in 1955, Uranium Fever talks about the rush that gripped the US from the late 1940s to the 1960s. It has an upbeat rhythm and ironic lyrics:

Well, you pack up your things

You head out again

Into some unknown spot where nobody’s been

You reach the spot where your fortune lies

You find it’s been staked by 17 other guys

Well, I ain’t kiddin’, I ain’t gonna quit

That bug’s done caught me and I’ve been bit

So with a Geiger counter and a pick in my hand

I’ll keep right on stakin’ that government land

Uranium fever has done and got me down

Uranium fever is spreadin’ all around

With a Geiger counter in my hand

I’m a-goin’ out to stake me some government land

But the real story of the Uranium Fever is far from uplifting, and we can find a strong commonality with the Fallout approach. In the years that followed World War II, the US experienced a new version of the Gold Rush – this time, instead of gold, many were gripped by the so-called “uranium fever.” An estimated ten thousand people headed to the Southwest attempting to make their fortunes in prospecting radioactive material. After World War II, uranium became particularly desirable after the end of the war had seen the advent of nuclear weapons with the bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It became quickly clear how important it would be for the opposite factions to arm themselves during the Cold War as the tension increased, therefore government agencies such as the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) sought after uranium for further research and development. Uranium was also shaping the landscape for nuclear energy and nuclear submarines, so it’s easy to see why so many prospectors attempted their luck in the Southwest, particularly Utah, Colorado and New Mexico.

Charlie Steen (nicknamed the “King of Uranium”) and Vernon Pick were among the few lucky prospectors who found their radioactive gold.

Both amassed quite extensive fortunes during their mining endeavours, and the Rush also saw many small towns in the area suddenly booming in population and size.

However, the uranium fever dried up pretty quickly: by the beginning of the 1960s, the AEC had enough material, and without the governmental demand for it, the uranium prices started waning, and the industry eventually collapsed, leaving behind a trail of ghost towns and bankrupt families.

Crawl Out through the Fallout

Written and performed by Sheldon Allman and released in 1960, its lyrics are perfectly suitable for the Fallout approach:

Crawl out through the fallout

With the greatest of aplomb

When your white count’s getting higher

Hurry, don’t delay

I’ll hold you close and kiss those

Radiation burns away

The song was released 8 years after the first nuclear reactor meltdown in Ontario, known as the 1952 NRX Incident, and just 2 years after a subsequent incident at the same facility (Chalk River Laboratories), the 1958 NRU incident. Both incidents attracted quite extensive media coverage, therefore the fear of impending nuclear doom was already very real in the 1960s. But Allman puts an ironic spin on it, perhaps as a coping mechanism, the same as Fallout does.

The music encapsulates a longing for a golden age made of soft music, dimly lit bars and an overall celebration of love and heartbreak. It’s a purposeful romanticisation of a world that, in reality, would be absolutely terrifying and almost impossible to live in: most of the Earth pulverised by atomic war, while the few remaining humans are killing each other for the few scraps left of a wretched world. Also, mutated beasts are wandering the wasteland.

The contrast between the landscape and the music creates a bitter paradox of levity, research for optimism and hope in a world devoid of it, which is perhaps the central core of what it means to be human: keep going through the most intense suffering while clinging to dreams of a better tomorrow or a better place.

While crossing the Glowing Sea, we can listen to Ella Fitzgerald telling us how in each life some rain must fall. Or while killing mutated beasts, June Christy tells us about the simple life and wanting tomatoes and mashed potatoes. It’s a reminder that eventually, all is meaningless, and maybe the best way to deal with it is to just ride it out as best as you can.

To close the article, I will gift you a curated playlist with the main songs. Hopefully you won’t have to listen to it during a nuclear fallout.

Sources

● Biopower and play: bodies, spaces and nature in digital games

● How Uranium Fever Shaped the 1950s Southwest

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.