Author: Amory Crane. Amory writes on Literature, Art, and wider cultural phenomena. He also writes fiction. You can find more of his writing here on his Substack and follow him on X at @LaughingCav1

All art is reproduction, but it is reproduction of a particular kind. The hand that draws the lover’s face reproduces not just the visual facts, nor only those which are gleaned by the reflection of light upon the retina, but mediates between these outer, or ‘tangible’ phenomena, and the inner, emotional response. This mediation, visible as far back as the Neolithic paintings daubed on the walls of the Iberian caves, is the fundamental character of all art. It represents man’s orientation to the world, not only physically — spatially, or topographically — but between space and his inner life, the subject and the object. It also reproduces a moment in time.

This mediation has inevitably found many iterations. The art of the 12th century differs considerably from that of the 17th. What differs may be accounted for by many factors, all of which fall broadly into two categories which themselves are commensurate with art’s concerns: social facts and inner feelings. When the oil painting took the principal place of visual expression in the European mind it brought with it, eventually, a new means of orientating man to his world: perspective. The world was put into focus upon the individual and with it, his sense of himself changed. Yet even this was open to further mediation. The revolution in the relations between man and God produced by Luther in the first half of the 16th century, or between man and woman almost single-handedly by Rousseau at the end of the 18th, undoubtedly shifted the consciousness of man’s relation to his surroundings even if they did not literally change his social facts — at least not immediately. The two shifting poles, then, between what there is and how a man sees are ultimately what produces a change in art. Those artists who in some way manage to assimilate a change in the social facts more fully into the inner life, or who manage to change those facts by the power of their inner vision, and who in so doing enable the greater part of mankind to see the world or some aspect of it naked for the first time are often what we describe, depending on the fashion of the day, as masters, geniuses, sages, or even just talented.

The question then, turning to what is the art of our own day concerned with, or even what is the art of our own day, must inevitably fall on the matter of what are the social facts and how we view them. These matters are beyond the remit of an essay of this length, but we may look at perhaps the one truly novel and characteristic form of visual expression which has arrived in the last decade-and-a-half and work inductively, to pick apart the fundamental characteristics of how we now reproduce our ways of seeing. I am talking here about the ‘meme’.

To do so we needn’t enter a gallery nor into the illustrious houses or impenetrable vaults of some noted collector. Or rather, we must first accept we have come to live in what constitutes a new gallery, a new museum; one in which we live a considerable amount of our lives and which we carry with us all hours of the day. This gallery has within it all forms of framed reproductions: news stories, photographs, videos, and text. These reproductions are themselves reproduced a myriad of times in a myriad of contexts, each one shifting or even reconstituting its meaning. And while it does not limit itself to artefacts of a purely ‘artistic’ nature, it does frame them. They are ‘curated’. Not by sharp-jawed young women in geometric-patterned dresses and chignon, nor by bearded obsessives in Harris tweed, but by the invisible hand of the coder. For the curation of today is algorithmic, not monolithic, and its masters have little interest in making sure everyone sees the same things (though it may desire to hide certain pieces of information), so much as ensuring that the right people see the right things. This then accounts for two important aspects of the meme as an artefact, both in how it is consumed and how it is produced. How did we get from the oil painting to here?

The first great shift in circumstance that we must quickly address is that from manual to mechanical reproduction. This matters because we must first understand how the hand which draws the lover’s face produces something fundamentally different — or perhaps, is producing something which is looked upon as fundamentally different — in a world in which that drawing can be readily and easily reproduced at scale and then mass-distributed. This is the landscape of our imaginative and visual lives, the root of so many of our social facts.

It was Walter Benjamin, writing in 1935, who first came to recognise the effects of this phenomenon and who remains in much their most preeminent register. He writes:

‘The reproduced work of art is to an ever-increasing extent the reproduction of a work of art designed for reproducibility. From a photographic plate, for instance, many prints can be made; the question of the genuine print has no meaning. However, the instant the criterion of genuineness in art production failed, the entire social function of art underwent an upheaval. Rather than being underpinned by ritual, it came to be underpinned by a different practice: politics.’

The first thing to note here is what Benjamin means by ‘genuineness’. Earlier in the essay he points to the effect of genuineness as being ‘aura’ — that feeling of a work of art being singular to a time and place, of bearing witness to history, of being a single instance from which copies can be made, but which retains nevertheless a unique value because of its authenticity. ‘The singularity of the work of art is identical with its embeddedness in the context of tradition,’ Benjamin tells us, and whether that tradition manifests itself as it did in its very first iteration, ‘in the service of some ritual’ or in a later, purely aesthetic manner, it relies on this very aura for its purposes.

Without this aura, art that is produced entirely out of purely mechanic reproductive methods — audio / visual media such as photography, music, and film — is left not with a single ritualistic or theological relationship to its viewership — aestheticism, Benjamin argues, is a kind of theology of art — but is always finding itself reproduced in a myriad of contexts: millions, even billions of different places at any given moment. In his time this would have been the cinema, the illustrated paper or magazine. Today, with social media, it is half our lives.

The meme then, represents a move beyond those media made possible by the shift from the authentic painting to the glossy reproduction to the cinematic film. All these phenomena were still reproducing — if mechanically — the world as man went out, saw, and interacted with it. It may have been selective, it may only have been partial, but then when was this not the case? No painting ever made claim to capture the entirety of life’s many shades, of all modes of human experience. What makes the meme different from digital art which apes the very style of visual medium it has begun to supplant — and which, as a consequence, has produced not a single notable piece of work — is that it reproduces not the lover’s face, or the vase beside her shoulder, or the building in the street outside, but the new world — the new gallery — the portal into which we carry in our pockets at all times.

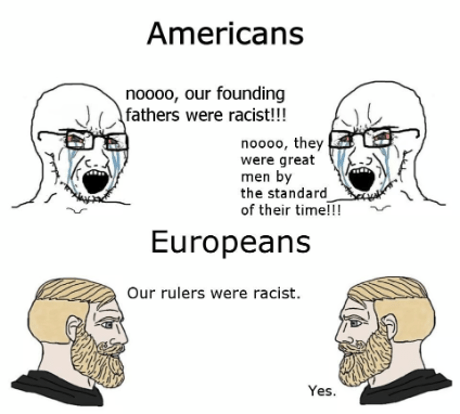

Compare, for instance, these images:

Once one views these two pictures side by side it quickly becomes clear that they are presented from two different sets of inner vision and address two very different sets of social facts.

The first is a depiction of a dual carriage or highway made in the medium of ‘digital art’; that is, visual productions which use direct-to-pixel forms in an equivalent manner to how the brush and the palette knife once met canvas. The second is a fairly representative meme featuring Wojak and chad. One is depicting the world ‘outside’ using a mode easily assimilable to us — perspective — orientating the world toward the individual, but dipping its toe tentatively in a new medium that does not appear to add anything to the old form. The second has no interest in perspective, and instead of orientating the spatial world ‘outside’ toward the individual, prefers to address the new ‘digital’ world on its own terms. These terms are collective. Thus we have, for instance, four collective or stereotypical characterisations: wojak, chad, Americans, and Europeans. The first question must surely be then to any viewer: which of these modes of reproduction appears to speak more directly to the experience of 21st-century man?

I am not here making a tacit aesthetic judgement on quality. I am merely trying to point out that while the first is an image instantly discardable without any appreciable interaction between it and the viewer, the second is an image the likes of which are made use of innumerable times every moment of every day. It reproduces something for which modern men have some expressive use and inchoate feeling. It does not attempt to represent a place. It does not attempt to represent a person, singular. It reproduces a characteristic set, or type of persons, and does so not by attempting to reproduce the world ‘in real life’ as we have come to refer to it, but that shadow world which we have described as ‘social media’. It does not, to stress the point further, orientate its viewer by placing him in a given moment and at its centre, but by placing his inner life and circumstances among one group and against another, and in essence among an endless stream (notice how one’s timeline never has an end). The oil painting, by giving the former illusion, attempted to deceive the viewer into believing a flat surface had depth; here, now, the meme has a separate purpose, which is to remind us that this digital world, with its high-definition visual and audio media, is, in fact, a two-dimensional but highly deceptive representation in the palm of our hands. How much more appropriate a depiction is this of the perspective of the man staring at the two-dimensional screen of his phone, the thousands of pieces of text and images passing before his eyes, algorithmically collated and made aggregate, than to attempt in some futile way to place him at their centre? In other words, the meme is to our digital world what the portrait or landscape is to our analogue, and what this tells us about the differences between these two worlds is appreciable not in the explicit message of any individual meme, but in its inherent form.

There is then a reason the lover’s face cannot be reproduced as a meme. Or rather, not the individual lover’s. The world it draws from, which it must cannibalise, is both its oil and its canvas, and this world does not place the individual at its centre, but is always collating and differentiating: not, to be clear, between one set of eyes and the world, but between varying groups of men. Wifejak is the most recent exemplar of the equivalent ‘lover’s portrait’, and whether or not one deems it a worthy depiction of womanhood, it should be noted it too attempts a verisimilitude of stereotype rather than of individuality. What piece of recent art had a greater amount of popular scrutiny of its actual meaning than this? King Charles’s portrait caused a storm of publicity this year, and while skilful, clearly did not speak to the intuitive feeling of man’s inner life or his social facts at this moment. The fact people such as Carl Benjamin, Academic Agent etc. felt it necessary to address the nature of the wifejak meme tells us something about the manner of the meme as a form and its importance to the contemporary mind.

It is then somewhat telling that any given photograph of an individual can easily be appropriated for these purposes, because digital culture removes the individual person from view and makes them always, in some way, a ‘type’. This effect has been intuitively grasped by the internet user, far more than the misplaced belief that any and all digitally reproduced depictions of a person on social media are a perfect representation of their inner life.

To illustrate, then, how the meme both depicts and draws from the environment in which it is situated, wojak is perhaps the preeminent example. The wojak meme is the blank-slate which is the foundational belief of our society. He is a neo-liberal man par excellence; the fungible token, upon which countless characters can be thrown. Chad, in contrast, is unmoving, hard, fixed. The reason liberal memes are in a sense contradiction in terms is that the very stuff from which the meme is made — the surrounding world of social media, the ‘gallery’ — is a reflection of the Neo-liberal culture. Yet this same culture, in order to produce a meme, would simply have to cannibalise and then regurgitate itself, adding nothing. This would go some way to explain the noted phenomenon of left-wing memes usually requiring so much more text to produce an effect. This is special-pleading, pure and simple: an attempt to explain itself away from the very culture which itself reflects.

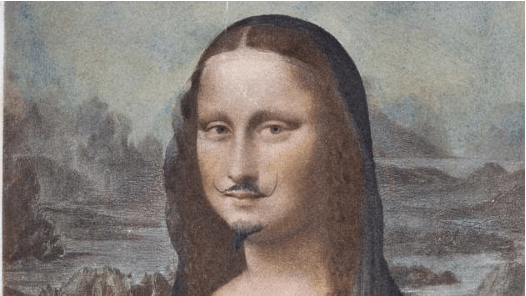

Heterodox memes reproduce but offer space for a new, different interpretation of the world they (and their viewers) find themselves in. The reason they succeed is that they meet this environment on their own terms. Not ideologically, but materially and in reflection of the intuitive experience of man in his new realm of social media. It does not persist in an ideology that runs counter to the very collectivising environment from and in which it exists. This is what Benjamin meant when he observed that art in the condition of mechanical reproduction has replaced ritual with politics. These artefacts are not conditioned by aesthetic concerns — they are not Rembrandt’s portraits; nor are they the conduits of worship — they are not Orthodox icons. They are conditioned by politics, perhaps the preeminent ritual of our own day, at least as far as it pertains to how we view the shadows of social media. Having no ‘aura’ in the manner Benjamin describes enables the meme to be reproduced and changed each time with no damage to its ultimate effect. Compare this to the inanity of Duchamp’s attempt at something similar a century ago (see picture below)

The irony, of course, is that in reproducing this image for you now, it already has more potential as a meme than it could ever possibly have done when it was made in 1919. This is because it still needed to be a physical object, and thus retained a modicum of ‘aura’, however attenuated, and the fact Duchamp is still known and credited as its author is notable. For someone now, however, to point at a meme such as the one I have illustrated above and to criticise it by saying, ‘you’re just piggybacking off of X’ would be ludicrous.

In eschewing all aura then, it follows that no one seems at all interested in claiming ‘ownership’ over the meme, nor really except in the most ephemeral of senses is this really possible. They are a truly popular form of expression, more so than the early modern woodcut or the satirical cartoon, because they are a means of recycling mass mediums for one’s own purposes, of reproducing a world which simply did not exist until a couple of decades ago. Anyone can produce them. The ordinary ‘man in the street’ (as it were) can produce amusing or biting criticisms of the status quo. This is what Benjamin means by the different, political ritual, underpinning the mass-produced artefact.

Given the means to cut up the very same media any given authority distributes — itself designed for the mass audience — and reconstituting it, the ordinary person then redirects the purpose of these artefacts, reforming prevailing narratives to voice their own. The total image is thus precisely undermined in the meme, which is why the meme has no interest in ‘real life’ verisimilitude. It thrives in absurdity, in pointing out glitches in the façade of political narrative and environment. The crudity of the meme above is a good example of this. Furthermore, these very ‘reshapings’ are not impervious to further reshaping, allowing for an almost infinite dialogue among the very people who produce them, ensuring no settled or totalised message. They are always unstable, washed away only by the shifting tides of the social media timeline: an art written into the sand.

This is why it has been said ‘Memes break the Internet.’[1] All revolutions in seeing are felt like this at first. In fact, while they may be breaking our old ways of seeing, they are not so much breaking the internet, as allowing us to see it for the first time.

[1] https://blog.artsper.com/en/get-inspired/memes-in-art/

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.