Author: Samuel Wild. Samuel is an artist working in painting and printmaking exploring vitalism and perennialism in art. You can find his work here.

Italy is warmer than you’d expect in January. I’d counted on this as I left a frozen and snow-covered Britain but actually experiencing the relative warmth directly after Christmas was jarring. Not that the Italians seemed to notice, wrapped up in coats and scarves as I, somewhat oddly given some of their expressions, had to take off my coat and walk around in a T-shirt.

So be it, this was how I felt as I looked down upon the Galleria Moderne Nazionale from the hill of the Borghese Gardens. Down some steps and crossing tramlines, you reach the impressive early twentieth-century building with its neoclassical yet distinctly Risorgimento design. I was here to see the exhibition Il Tempo del Futurismo, which started in December and will run until the end of February. The exhibition supported and promoted by Giorgia Meloni’s Ministry of Culture and curated by abstract art specialist Gabriele Simongini displays 350 futurist works, some that have never been gathered together or ever left Italy.

The exhibition was prompted by the eightieth anniversary of the death of the prophet of modernity Filippo Marinetti who died on 2nd December 1944, just before the end of the Second World War. The exhibition is certainly a celebration of pre-war Italian culture, and one wonders how much this is reflective of new attitudes in Italy’s highest ranks. In any case, as I entered this beautiful building on a surprisingly warm January morning, I was overwhelmed by the achievement of Simongini and the Galleria.

The inclusion of the Italian word “Tempo” into the exhibition’s title is apt. The visitor is carefully guided through the entirety of the Futurist movement from its very beginnings, through its various evolutions until its end and moreover through a rhythmic series of beats. It behoves us then to play through each bar of this exhibition chronologically.

The Origins of Futurism

It is a common misconception to believe that Futurism comes from an elaboration of the earlier French Cubist movement, as a kind of Italian ‘moving cubism’, complete with gesticulations. Nothing could be further from the truth as the curation of this show demonstrates very well. Futurism originates in Italian Divisionism, the later impressionist technique where the painter applies small dots and dashes of unmixed pure colour to create a sense of fresh light when one backs away from the painting and the dots of colour optically mix. This technique was pioneered by artists such as Seurat and Signac in Paris who wished to create a more scientific impressionism.

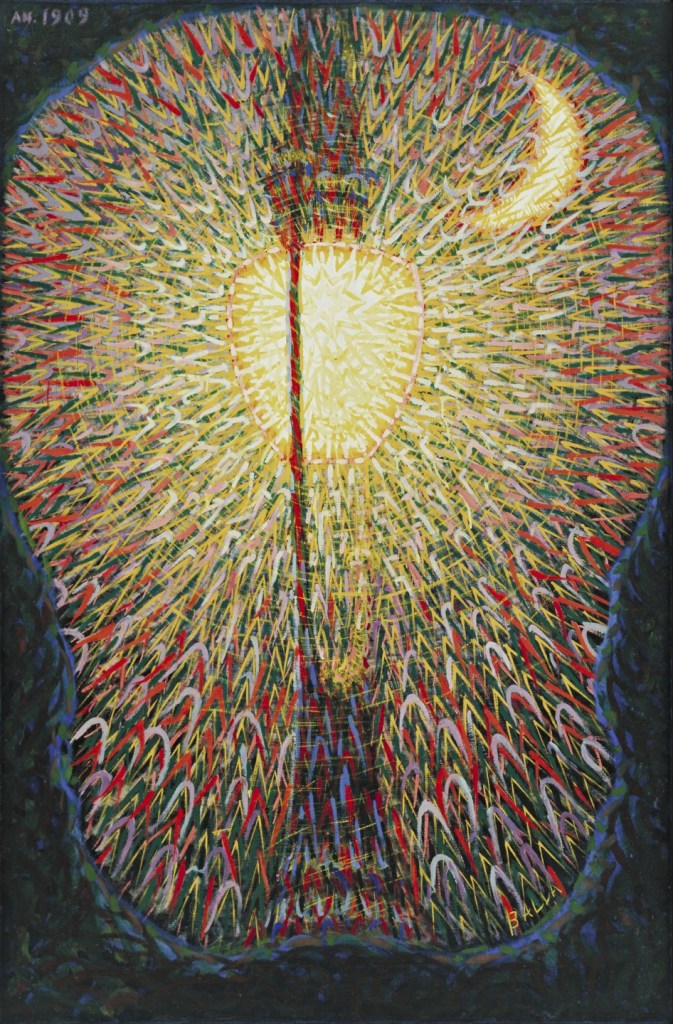

As one enters the first rooms of the exhibition the Italian Divisionist movement is well represented with such artists as Giuseppe Volpedo and Giovanni Segantini. These were the grandfathers of Futurism as all the core Futurists (Boccioni, Balla, Severini, etc) were all young followers. The lesson that they took from these masters was that painting and the world around them is an interpenetration of all things. As the atoms of red and blue optically mix to create green, so too do atoms mix to create the world. Everything mixes and is interpreted through their relationship to the whole. This commonality between the Divisionists and the Futurists is brilliantly demonstrated by contrasting Volpedo’s work Rising Sun (1904) with Giacomo Balla’s Street Lamp (1909).

Volpedo’s impressionist painting is an agrarian and mystical vision of sunlight illuminating earth which mankind struggles to cultivate for their daily bread. Divisionists were often connected to the agrarian anarchism of Southern Europe, where oppressed men and women worked the land in communal living. Balla uses the techniques of Volpedo but for radically different aims, to “block out the moonlight” as Boccionni put it. Modernity overpowers nature with an attack of force and the Futurist philosophy is born. It is Divisionism turbocharged by electricity. In these initial rooms, the exhibition demonstrates that unlike their forebears the Futurists were much more interested in the world of the city, in factories, in technologies and in the fashions of the day. They still wish to represent the world around them, and in this, they show their impressionist roots, but for them, the world is of steam, electricity and radio.

The key Futurists are introduced early on. Umberto Boccioni and Balla emerged as clear leaders in the early days, followed by Luigi Russolo and Gino Severini. Oddly the illustrator Romolo Romani is included here, he was primarily a mystic symbolist, but he does share the Futurist concern with the interpenetration of all things.

Heroic Futurism

From three rooms that detail the origins of the movement, we progress to a large room where the show delineates the movement’s first flowering from the Manifesto of the Futurists in 1909 until the start of the First World War. This is the heroic age of Futurism, the time that made its name. Marinetti enters the picture as up until this point he was hidden away in Paris. It is obvious that he provides energy and new perspectives to the artists as they begin to experiment with Parisian cubism and become obsessed with speed, movement, and technology. The exhibition beautifully shows this by including contemporary motor cars and motorbikes next to the works of sculpture and painting. A shining red Maserati race car provides an amazing spectacle whilst next to Boccioni’s sculptures. One is immediately transported to a time of vast excitement and ambition. The genius of Boccioni becomes very clear here. The exhibition lacks some of his major works, his The City Rises (1910) and the Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), the former probably closely guarded by the MOMA in New York. That said it becomes clear that he is the primary thinker in this period of the movement and his unique genius is to transfer the Futurist philosophy into sculpture, something no other artist seemed able to do.

In this part of the exhibition, the curators really show us the philosophical depth of Futurism beyond the gimmicks of moving figures in painting etc. Boccioni had a cosmic Heraclitian vision of man and the universe aided by modern science:

“Our plastic-constructivist idealism takes its laws from the new certainties given to us by science… Let us not forget that life resides in the unity of energy, that we are centres that receive and transmit in such a way that we are indissolubly bound to the whole… The electrical theory of matter, according to which matter would only be energy, condensed electricity, and would exist only as Force, is a hypothesis that increases the certainty of my intuition…” Umberto Boccioni, Futurist Painting Sculpture (1914)

He really wished to represent the world as his intuition told him was true, that modern science had confirmed, and that motion, energy and speed were the absolute core of all things. It’s an inspiring and convincing metaphysical vision in our modern age and it was very moving to see how the exhibition honoured this modern master.

What the exhibition makes clear is that cubism was one language which these artists picked up in order to express their own peculiar vision, as innovations in poetry would be for Marinetti. In this sense they are fundamentally different from the Cubists themselves, who were exploring a new way of expressing form for its own sake, and from Marcel Duchamp, who is represented in the exhibition with a study for his Nude Descending a Staircase (1911). The machismo obsession with speed and machinery that the Futurists demonstrated would shortly be ruthlessly satirised in him and fellow Dadaist Francis Picabia in their pseudo-sexual painting of machinery. A virtue of this show as compared to earlier ones, especially the Futurism show at Tate Modern in 2009, is that it is laser-focused on Italian Futurists and doesn’t confuse them with other channels and dispensation of their time.

Another intelligent link made in this exhibition is with the Italian innovator of radio Guglielmo Marconi, who himself had an interest in the movement and visited the studio of Balla. Radio is also a great metaphor for the Futurist aesthetic and the exhibition makes this explicit by juxtaposing Marconi’s steampunk radio setups and the movement’s cubo-futurist paintings. This is where the show’s content becomes very relevant for us today. The interpenetration of instantaneous communication that radio gave the world was just another part of the overall Heraclitian philosophy of Boccioni and Marinetti. Thought is as much energy as matter, and they believe it must be projected and received from and to every corner of the world. The futurists could be called the grandfathers of internet accelerationism. As I passed through these large rooms, I wondered what Baudrillard would have thought about all this…

Abstract Futurism

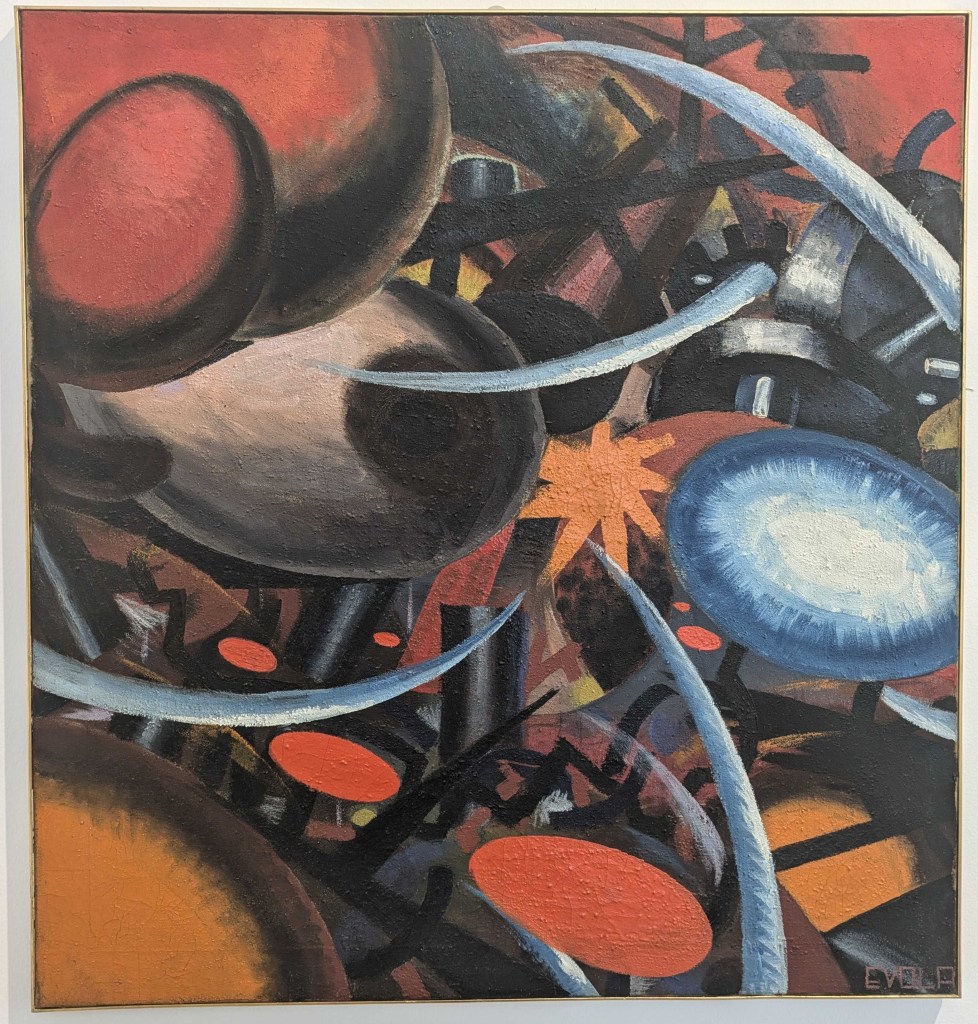

During and after the war, with Boccioni dead, Balla becomes the main focus of the exhibition. We see curator Simongini’s speciality come to the fore. In this period Balla enters a fully abstract style. I wasn’t aware of this fervour for abstraction in Italy at this time, but Balla and a group of younger artists wished to “reconstruct the world” in an analogous abstract visual language that would communicate the real truth of the universe. He was joined by a generation of younger artists, like the playful Fortunato Depero and the thoughtful Julius Evola.

Balla is at his best here when he adds some symmetry and harmony to his abstractions, such as the Expansion of Spring (1918), where beautiful, rounded forms come together in organic shapes, as if one is seeing a flower as pure radiation. Spirituality becomes more important to Futurists after this point and one can see why in the aftermath of the war. The painters of this period never abandon their futurist philosophy but there seems a clear change of focus that the show brings out well. I couldn’t help seeing in the paintings a glimpse of Evola archetypes and timeless alien forms coalescing and diverging in metaphysical symphonies. It’s as if the young philosopher was giving his inscrutable ideas physical shape, trying to reflect upon a broken world.

Rational Futurism and Art Deco

From here the exhibition showcases the work of the second generation of Futurists. These artists like the painter Enrico Prampolini and Gerardo Dottori, and the aforementioned graphic designer Fortunato Depero, amongst others, created artwork that desired much more structure than the Heraclitian visions and spiritual dreams of Boccioni and Balla. They also spread Futurism out from the confines of painting and sculpture and into the world of design and craft. This comes with mixed results. The aesthetic of futurism doesn’t necessarily gel with the functional structure of furniture, of which there are some examples in the exhibition. The result seems to be adding exciting colours and shapes to basic objects. The designs of Art Deco designers and the Bauhaus are far superior to these efforts.

They succeed much better in the more sympathetic mediums of graphic design and textiles, as in the fashion designs of Balla or the humorous posters Depero made for Campari. Here we see the merging of Futurism with the general trend of Art Deco although this is not made explicit by the show. What is made clear is the popularisation of Futurist visual language in advertising and media during the 1920s. Usually, this isn’t as innovative as the painting and much more regularly ‘figurative’, as on Federico Seneca’s posters, that said, to an ordinary Italian in the interwar period all this new media must have been desperately exciting, and that has to be the essence of the movement.

The painting here takes on more rationalised compositions. This may reflect the cross-continental drive to ‘Le retour à l’ordre, the idea that too much innovation had taken place prior to the war and that art needed to develop more grounded methods. For these artists, groundedness comes not from classical models but from rational organisation, and this is displayed well in the work of a painter like Prampolini and his painting The Geometry of Voluptuousness (1922). The work is generally less intellectual and much more corporeal and sensuous. When confronted with this work I was compelled to make connections to the work of American Art Deco, particularly artists like Tamara de Lempicka and Charles Demuth. Was Italian Futurism of the 1920s actually becoming more internationalised at this time? Joining the international decadence of the Jazz Age? And in particular, finding better connections in the new country of the USA rather than the France of Paris?

“Aeropainting” and Fascism

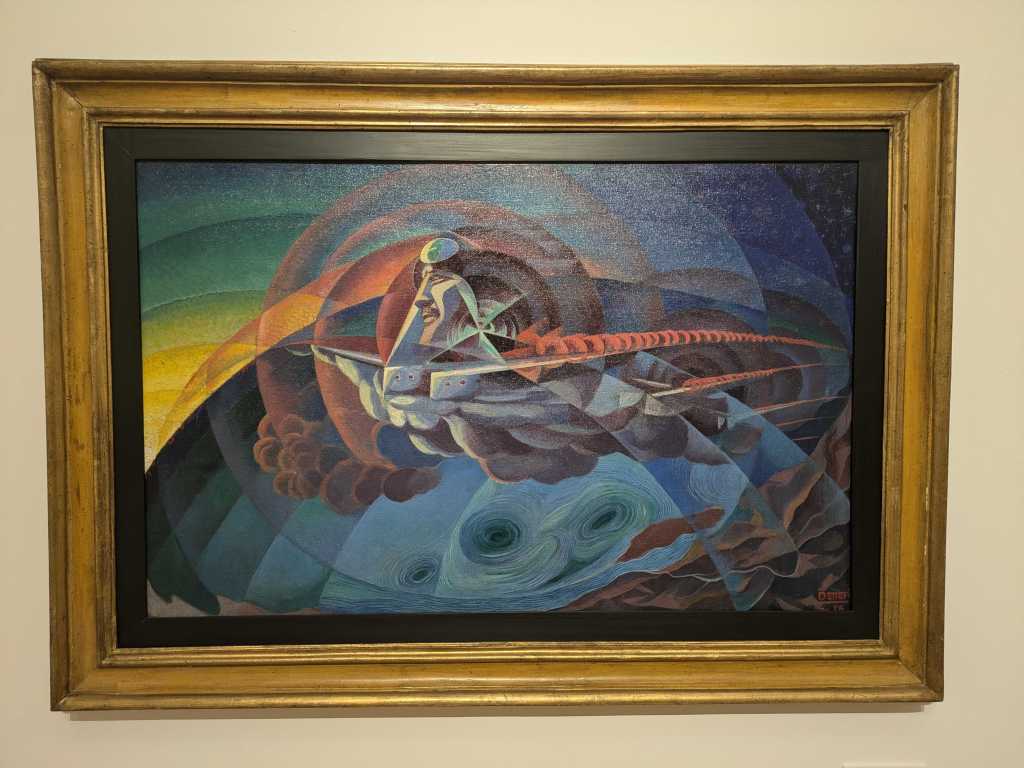

These questions are not directly answered by the exhibition, and neither is the rise of Il Duce. Mussolini is very much a side character in the story that the exhibition presents and is neither damned nor praised. What is perhaps more interesting is that from the late 1920s and through the 1930s the focus of Futurist art changed significantly, and I couldn’t help thinking that Fascism had some effect here. Firstly, in terms of formal analysis, the point of view of the paintings changes. The paintings of this iteration depart from the subjective vision of former impressionists like Boccioni or Severini and also depart from the painting as an abstract object like modernists Balla and Prampolini. These paintings desire a bird’s eye view.

The exhibition dramatically communicates through the inclusion of a huge Macchi Mc-72 sea-plane – this is due to the absolute mania for aviation in Italy in the 1930s. All of the remaining Futurists, including Marinetti, seem to have seen within Italy’s race towards air power an opportunity to break the chains that hold down the human spirit:

“The changing perspectives of flight constitute an entirely new reality, unlike the traditionally established one of the terrestrial perspective” The Manifesto of Futurist Aeropainting, 1931

Here Futurism has a new cause, ‘Aeropainting’, and has allowed itself to dream of heroism again. In doing so they attempted to throw off the shackles of traditional perspectives, the perspectives of Piero della Francesca and the Renaissance. This led to some amazing paintings, such as The Flyer by Dottori (1931) or Alfredo Gauro Ambrosi’s Coming down to the City from the Sky (1933). It felt like a real blessing that the curators had made the choice to include the Futurist movement far beyond the canonical high usually put in art history books as aeropainting came as a revelation to me.

Alternatively, this part of the show also includes The Head of Mussolini by Renato Bertelli (1933), which felt like a look back upon the work of Boccioni. As great as this work is, and it does achieve an amazing illusion of spinning movement, I couldn’t escape the feeling that something of Boccioni’s heroism had been lost. The Head seems to have a total surveillance of the area around it, like a metaphysical CCTV camera. This was a time of totalitarianism and regardless of its goods and evils, it seemed to contradict the expansive nature of those earlier phases of the movement.

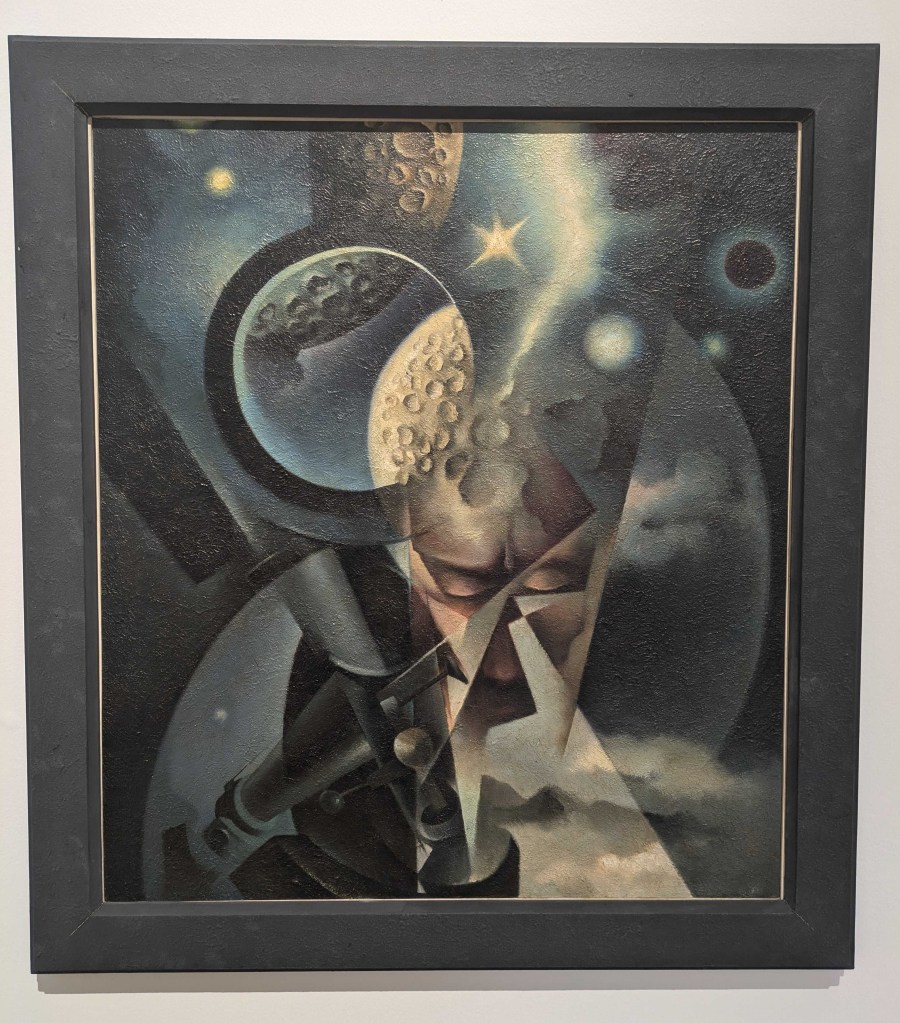

But in this, the exhibition presents one with the genius of Tulio Crali, who kept the torch of Boccioni alive in the 1930s in such works as Man and Cosmos (1933-1934). In this painting we see that same spirit of exploration we saw earlier as the human mind looks both down the microscope and up through the telescope. He continues his journey into aeropainting itself with Inception-style paintings like Great Overturned Vault (1938), where the world is twisted and stretched under the pressure of speed itself. Surely Crali lived up to the ideals of aeropainting.

Futurism Now

At the end of the exhibition, we see the artists of the later generation absorbed by Surrealism or mid-century abstraction, which the show tries to convince us is a continuation of Futurism. It was a sad sight. The essence of the movement was heroism and energy, changing the world and being changed by it. Surrealism, or Cosmic Idealism in its Italian form, is of a totally different spirit. Mid-century abstraction has a better claim to hereditary but seems fossilised in comparison. And then of course there is the compulsory connection to contemporary art. Futurism really died after the Second World War and if this show teaches us anything it’s that Futurism was anything but ossified. It yearned for freedom and vitality.

Despite missing some key pieces as mentioned above, this show has to be the best one yet in terms of getting to grips with the depth of Futurism and showing its complete life span. Other shows, like the 2009 show at the Tate Modern, seem confused and limited in comparison. It is stubbornly Italo-centric, which is a relief in a historiographical context where the internationalism of modern art movements is emphasised.

Is Futurism still relevant to us? Without doubt but in two certain respects, one contextual and metaphysical. Contextually, we still live in the same modern world as the Futurists. Technology is rapidly changing our consciousness and our societies. Is this for better or worse? The Futurist answer is for the better and we need more of it as quickly as possible. As stated above, they were the accelerationists of their day and in this sense, they are still relevant as precursors. Metaphysically, they are relevant because they extolled an essentially pagan and Heraclitian view of the world as energy and force. Strip away the technology and the science and you have an emotional view where all things give out energy and receive it, things are born, burn up, flower, decay to ash and are then reborn – that is the emotional core of Futurism and that will be eternally relevant to men and women who still have a warm pulse in their veins even in spite of the coldness of our season.

You can still view the exhibition at La Galleria Moderne Nazionale in Rome. It will be running until 28/02/2025: https://lagallerianazionale.com/mostra/tempo-del-futurismo

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.