Author: Adam Gorecki. Adam is a London-based writer, maker, and photographer with a broad love for anything that catches his curiosity, particularly music. Graduating with a Level 4 Diploma in Copywriting from The College of Media and Publishing, he sees music as a complex social study and is fascinated by how brilliant ideas can be brought to life. He has a critical eye for great storytelling and thrives in exploring the philosophical side behind an artist’s intentions and what can ignite a spark that lasts for generations.

According to Sigmund Freud, the ego is the part of the mind that balances between the animalistic desires of the ‘id’ and the socially acceptable standards of the ‘superego’. In other words, it’s the part of our mind that helps us navigate the world as a way of defining our own identity.

A major part of our identity is our ability to create things, to think obscurely and to achieve the ultimate goal of creating something that not only resonates with others but also with ourselves. Many creative people go through life fearing they may never be recognised for their unique contribution towards the world. So, you can imagine that when artists finally get public recognition for their unique outlets and are praised for it to the highest standard, you can’t necessarily blame them for their ego’s imbalanced perspective of themselves. Now, imagine a group of these people in a room. Do you imagine them committing their efforts towards producing a singular astounding work of art? Or perhaps clashing in order to produce an independent representation of themselves instead? The two outcomes may not turn out to be too dissimilar. When I began researching the public considerations of ‘all-time classic albums’, ego conflict seemed to be a pretty obvious but great place to begin when it came towards adding fuel to the fire of a project.

Objectives for new groups often begin as innocent; either with a shared creative, political, conceptual or musical incentive. However, the crucial aspect is having the ability to create something that simply works beyond explanation or analysis. This can either grow or die out. If it dies, it dies. But particularly from the 1950s and beyond, artists were extremely susceptible towards reaching a ‘cult-like’ status which hadn’t been seen before. A sense of worship that came from members of the public believing to have found a work that is ‘beyond themselves’. Is this natural? Probably not.

THE BEATLES

John Lennon described The Beatles to be “bigger than Jesus Christ” upon their 1964 debut trip to America which caused a major uproar at the time. Similarly, the three-way ego war between Beatles members McCartney, Lennon and Harrison likely triggered the group’s highest experimental peaks, as well as the group’s inevitable demise. Although I can’t put a finger on an exact ‘classic’ album that defined the group, it can be argued that the death of Brian Epstein and the withdrawal from touring (and the influence of experimental drugs) sparked an unwarming sense of exposure and sense of lostness for the group that spun them into an ego enthused oblivion. In other words, it placed the boys in the position to begin finding themselves.

The Beatles’ self-titled record (known as The White Album), is critically acclaimed to be one of their best, as well as being considered to be the beginning of the end for the band. Rolling Stone magazine describes ‘The White Album’ as “four solo albums under one roof”, Lennon going as far as to say that “The breakup can be heard on that album”. Without a managerial leader, the lads’ path to self-discovery led towards major creative and personal contradictions. McCartney had taken a self-imposed role as creative lead from around 1967, guiding the group towards whimsical works such as Sgt Pepper, but whacky commercial flops such as The Magical Mystery Tour’s film (although I very much love the soundtrack).

Furthermore, McCartney’s meticulous and melodic (although at times, substance-lacking) songwriting methods clashed with an LSD-enthused Lennon’s raw, insightful but heavily political style. In reflection, it often seemed that Paul represented doing things ‘for the fun of it’, whereas John was always about ‘the purpose’. However, both saw each other as talented writing equals. Dangerously, both underestimated their ‘little brother’ George Harrison. If you were to contrast the illustrative efforts of ‘Ob La Di Ob La Da’ against ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, the divide in artistry is evident. Harrison took his role as the band’s ‘dark horse’ admirably. Inspired by his visits to India, his spiritual, emotional and meticulous style of writing would appear as only a few songs on the final few Beatles records. The 1970s ‘Let It Be’ documentary would tease a glare across the practice room from George to Paul that would say ‘I can do it so much better than you’. Often having his work dismissed or adjusted by his ‘older brothers’, it fuelled the ‘quiet Beatle’ to attempt to leave the band in 69 and eventually be the keenest to sign the leaving documents the following year.

But why did this create such great work? Why did it give us projects such as The White Album, Abbey Road and even (in my opinion) Let It Be? Well for starters, it wasn’t a comfortable recording environment. Unbearable, even for sweet-soul Ringo who left the studio due to tensions in 68. George Martin, producer and ‘Fifth Beatle’, abandoned the studio to go on holiday. There was a likely sheer sense of desperation, the love between the boys was being strained to the very nerve. McCartney was tightly holding the strings of his creative baby like he was trying to save a crashing jet. Lennon was suffering from conflicting feelings of suicide and romantic confusion between his family and new love for Yoko Ono (you can hear it in the strained screams on Yer Blues and I’m So Tired) and Harrison had a simple desire to leave and embark on a spiritual pursuit. Yes, there was most likely a sense of competition between the members but above all else, when an artist is in pain, they express themselves the only ways they know how – through creating great music. In the late 60s, I can see the desperation coming from a fear of, a love of and envy of each other. The outcome is a splatted tapestry of complex emotions, confusing to navigate or completely make sense of as a project. But that sounds like a lot of what it means to be human. I think that’s what made this era of The Beatles so great, we could all relate to the chaos, confusion and indirectness of themselves. I like to think that we have a variation of each Beatle in us somewhere.

PINK FLOYD

So, we’ve established that the fuel for this exceptional run of projects was heavily powered by a dying love between the boys during a very confusing time for them all. But is this the only form of internal conflict that stirs the creative pot? Certainly not. The peak of Pink Floyd in the mid to late 70s was known to be charged by a ruthless struggle. This time, not one that grew from emotion or love, but rather a sharpened desire for power and creative control. It was described by lead guitarist, David Gilmour in Guitar World Magazine as ‘egocentric megalomaniacal tension’. Unlike The Beatles, it didn’t seem to me that Floyd shared the same ‘brotherly love’, although there still remained a deep respect for each other’s craft. Between the band leads Gilmour and Waters, their shared need for band control triggered a culture of dishonesty, manipulation and in some cases, sheer dictatorship. Roger, like Lennon, was known for his heavy political stance and prioritised establishing a firm concept on a record. As his control of the band became more firm on projects, he also nearly completely absorbed the role of lead singer and songwriter. Although Waters was reliable for producing consistently intriguing and mystifying concepts for Floyd’s records, his (over) prioritisation of lyrics often sacrificed a suitable melodic vehicle to carry them in. This was the area where Gilmour typically thrived. An outstanding guitarist who prioritised structure and melody has left no room amongst Roger’s clever and calculated concepts for any genuine moments for majestic instrumentals that Floyd was so well known for.

Were either of them right? Yes, of course, they both were. Floyd’s mid-70s run of back-to-back classics (Dark Side to The Wall) is no coincidence. The band needed compromise. However, they had little opportunity to achieve a perfect equilibrium. The inevitable success of Dark Side Of The Moon in ‘73 triggered a firm sense of confidence in Waters and is what ignited a gradual transition of power as creative lead. Did we find a ‘sweet spot’ in this transition? Certainly. Wish You Were Here and Animals hold a near-perfect ratio of insightful, prophetic lyrics that work hand in hand with long, miraculous pieces of psychedelic solos as a near-perfect ratio. This didn’t prevent tensions from rising throughout recording sessions. In fact, it heightened them drastically. Water’s ‘concept’ driven approach directly clashed with Gilmour, Mason and Wright’s more collaborative methods. The creatively fruitful leadership style would eventually cause the demise of Floyd’s successful album run into the 80s and beyond.

So in an attempt to end this conflict, Waters left the band in ‘85 and the band continued to release music without him (against Rogers’ wishes). Almost immediately, the absence of Waters proved that the chalk and cheese of the two group leads was exactly the catalyst that Pink Floyd needed in order to continuously capture lightning in bottles. Their thirteenth studio album, A Momentary Lapse of Reason (the first without Waters), was evidently a Gilmour-led operation and heavily built around his melodic structure. Although having standout tracks such as On The Turning Away, it would never be the Floyd we remembered and loved. It felt too safe, too tranquil and without a concept.

When writing this article, I had the aim of discussing three separate examples that fall under producing classics in a heated conflict. I don’t think it would’ve been particularly hard to think of a third band that achieved such a thing. Fleetwood Mac with Rumours screamed to be the most obvious, The Rolling Stones were another given. When exploring these options, I couldn’t help but feel I was just swinging around in circles. Yes, if you place talented people in a booth with enough industry pressure to produce an all-time classic, it’ll evidently end with them tearing each other’s throats out. What I’ve failed to explore thus far, however, is the internal conflict. These themes of ego, competition, doubt and creative control don’t have to solely rely on existing external parties. As far as I’m concerned, these are all things you can share with yourself, should you be in that head space.

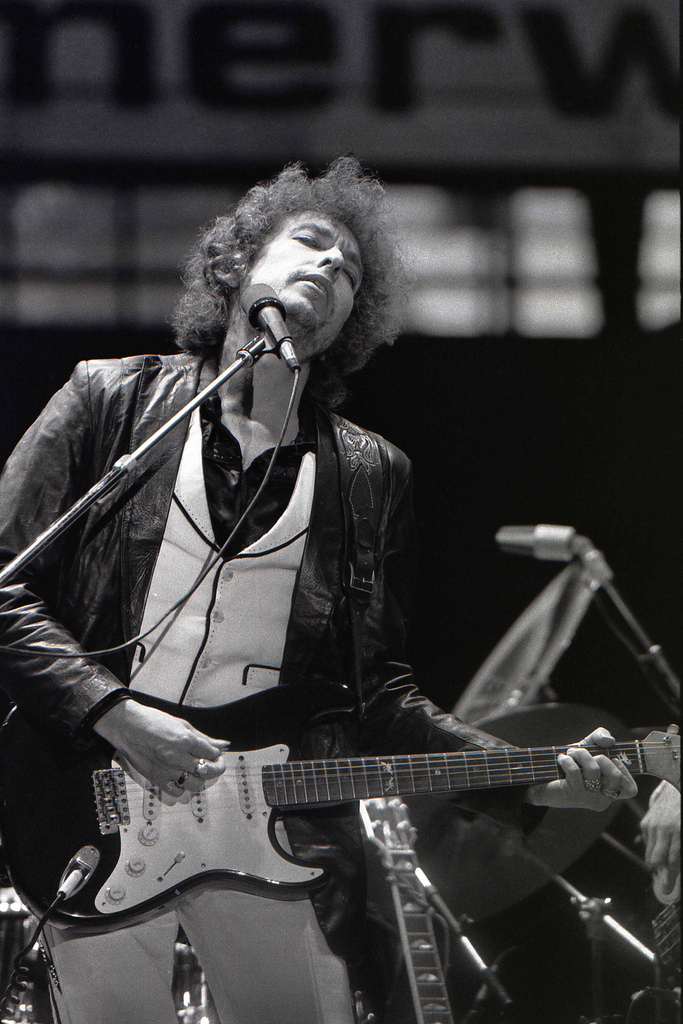

BOB DYLAN

I don’t believe that Bob Dylan particularly suffered from having an inflated perception of himself. He was a bit more of a feeler, and being so in touch with that side of himself restored confidence in the art that he produced. He became a mouthpiece for the events that surrounded him and illustrated a gravitating vision of what he believed the world was and what it could be. This meant, throughout his long career, his subject matter was gracefully woven in and out of whatever managed to reach his creative antennae. Being known as one of the greatest songwriters to walk this Earth, I find it fascinating that conflict still has a part to play with one of his highest regarded pieces of work – ‘Blood On The Tracks’ (1975). This time, however, the artist was in conflict with himself.

At least with band members, the collaborative effort of different individuals will form a tangled blend of quirks that echo throughout the music. A vortex of characteristics that form a concept with such a unique texture. However, whether it’s the insufferable turmoil of heartbreak or depression, it’s your own perspectives that flip upside down and are rapidly spun around. I’d say that the emotional confusion behind a heartbreak can ignite multiple versions of yourself to come alive and collaborate. This heartbreak, in particular, stemmed from the slow and gruelling deterioration of his relationship with his wife, Sara Dylan. Son, Jakob Dylan, went as far as describing the album as “my parents talking”.

Indulging in his own mystery, Dylan far prefers to leave his work to our own interpretation.

According to The New Yorker, Dylan claims there’s no autobiographical resemblance. Sure. What we witness here is a resurrection of Bob’s creative outlet after years of emotional strain and mediocre projects, reignited through a series of painting classes he attended under Norman Raeben.

“Raeben taught me how to see … in a way that allowed me to do consciously what I unconsciously felt … when I started doing it, the first album I made was Blood on the Tracks. Everybody agrees that was pretty different, and what’s different about it is there’s a code in the lyrics, and also there’s no sense of time.” [1]

Ultimately, what we receive is the most honest, clear, brutal and detailed storytelling from Dylan. Unlike most heartbreak albums which usually only depict the more agonising sides of a breakup, BOTT gives us the sense of an entire relationship. The highs, the lows, the mixed feelings, the different stages and in all kinds of depths. It can be described as ‘depressingly happy’. For example, on the hooks of songs such as ‘You’re a Big Girl Now’ and ‘Idiot Wind’ there’s a very heavy, deep, and relieving wail that comes from Dylan. The painful wail is a collaborative one, formed under strain. It feels like a release of not just the bad times, but also a farewell to the good. It comes from many confusing, reminiscent places and that’s what makes it real. Still on Idiot Wind, the pitch of the organ and the heavy thump of the drums continuously follow Dylan’s cadence impeccably. It speaks loudly, with a sense of fearlessness towards these emotions… but it’ll still be followed by lyrics such as ‘I can’t even touch the books you’ve read’. Other songs, like Shelter From The Storm, are storytelling masterpieces that dance along the line of reminiscence. The song is a recollection of his former relationship with Sara. He makes his peace with a very simple but heartbreaking statement –

‘And if I pass this way again you can rest assured

I’ll always do my best for her on that I give my word

In a world of steel-eyed death and men who are fighting to be warm

“Come in,” she said

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”’

Now, I could write an entirely different article on the lyrics behind this project (and one day I most likely will), and there’s so much that I’d love to be able to cover about this album. But I’m trying my best to stay on track here. Dylan suffered an artistic recession during the early 70s, I believe that his internal conflict during this time ignited his creative revival. There’s a surrender towards his mystical self that he had kept hidden for many years. Although he refuses to admit it in the public eye, I think that this was the dawn of Bob showing the world who he really was. Following this we’d see albums such as story-heavy ‘Desire’ or ‘Saved’ where he claims himself as a ‘born again Christian’. On BOTT, Dylan merged his two creative differences as a folk and electric artist (at this time, the two had existed but never completely worked as one). I think that by giving up his mystery persona and political stances, he managed to unlock a new level as a creator and gained the ability to resonate with others on a deeper level.

This album was a turning point that sustained his status as a long-term legend – and it all came from making peace with his internal conflicts that had stuck with him for God knows how long.

Perhaps it’s slightly pessimistic to say that a classic body of work should give credit to the bitter feelings of hatred, conflict, heartbreak, jealousy, sadness and suffering. But for anyone who argues that I’d imagine they’d struggle to get a grasp on finding a sense of introspection in any musical project. In times of hardship, we tend to have to bear with numerous variations of emotional states. To form a musical project with a singular positive emotion at heart is not only untrue but no different to painting a canvas in one colour. Funnily enough, I’ve seen single-coloured canvases sell for millions in art auctions, but that doesn’t mean that it can make a widespread impactful impression on someone’s life when they see it. Money simply doesn’t equate towards the ability to resonate with others. Now of course we have happy music, sad music, angry music, etc. But those all-time classic records seem to fabricate some obscure, grotesque yet obscenely gorgeous works of art that simply can’t be described in a singular word. A bit like when you hear some terrible news, and you say that you’re speechless. The complexity of pain, love, heartbreak and all the in-between are some of the human race’s deepest luxuries. If you’re privileged enough to feel such a thing, I can guarantee you will emerge as a more complete and insightful person. That is if you choose to accept those emotions. It’s very much like listening to some of these classic albums. Torment is capable of producing such beautiful pieces of work because it forms a mirror that we’re able to look into… but never thought we’d be able to see it. In this article, I gave three examples of mainstream 60’s – 70’s musical icons who I believe illustrated this theme perfectly. That’s not to say it can’t be found anywhere else. I think the reason why I love music so much is that it has such an intricate ability to physically represent the emotions we struggle so hard to express otherwise. It’s why I believe everyone loves it, really. The chances are most of our favourite albums will give a good insight into who we really are, that’s what great music is all about at the end of the day.

Sources

[1] Clinton Heylin (April 1, 2011). Behind the Shades: The 20th Anniversary Edition. Faber & Faber. pp. 368–369

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.