Author: Gavin Duffy. Gavin graduated from Strathclyde University with an MSc in Historical Studies and has had a general thirst for knowledge from a very young age. His main passion turned towards history which led him to his degree and also his work in museums such as the David Livingstone Birthplace. He has a wide range of interests both academic and non-academic and has a strong belief in exploring the fullness of life and the world.

WHAT WAS THE CHETNIK MOVEMENT?

The Chetnik movement in Yugoslavia during the Second World War was one of the most impactful organisations in the political sphere of the (ex-) Yugoslavia region. The legacy of the Chetniks and how they are remembered are important factors in Serbian nationalism and self-identity and in Serbia’s relations with the other constituent republics of Yugoslavia.

WHO WERE THE CHETNIKS?

The Chetniks were bands of warriors in the Balkan mountains, and their origins were in the 19th century, during the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Many Balkan countries have these figures known as ‘Hajduks’ who operate as small-scale guerilla outfits that were common in various Serbian rebellions in the 19th century, as a result of the growing Ottoman repression – it meant resistance was only possible in small bands or mercenary forces in foreign armies[1], indicating a long history of paramilitarism in the Balkans that will influence later conflicts.

The Chetniks began to take a more solid form during the First World War era, which was a turbulent period in Serbian History with succeeding wars with the Ottomans, Bulgaria and the Central Powers in the First World War in a few short years.

CHETNIK’S IDEOLOGY

By the time of the Second World War, the Chetniks had an ideology of Serbian monarchism and nationalism that put them into conflict with other nations in the Balkans and with Communist Partisans. The Chetniks have always been key in Serbian irredentism as noted by Tasic who notes their role in the Serbian attempts to assert influence over Macedonia against their Greek and Bulgarian rivals.

The Chetnik’s role in the resistance has been debated since the end of the war. Many Serbs were driven into the Chetniks (and Partizans) not necessarily by strong ideological conviction, but by the cruelty inflicted upon their people by the Croatian Ustaše regime, so much so that the Nazis found their genocidal fury to be counter-productive by fortifying the counter-resistance.[2]

The Chetniks were primarily composed of younger boys and men who were just school-age or not much older. This made them more vulnerable and less capable or even culpable of understanding or being held accountable for the Chetnik cause.[3] To some extent, they could be given the benefit of the doubt considering the Chetnik belief that a total extermination of the Serbian people was underway given the brutality of the Nazis and Ustasa.[4] Glenny’s view here is a more modern assessment of the demonisation of the Chetniks that followed the Socialist Yugoslav regime.

Other authors paint the Chetniks as an aggressor force, particularly towards Muslims. P.J. Cohen notes a long-standing hatred towards Bosniak Muslims who are often referred to as ‘Turks’ and conflated with the Ottomans in Serbian culture throughout the ages.[5] This coincides with the view that Tito took the Chetniks as collaborators and genocidal extreme nationalists, with merely window dressing separating them from their Croatian counterparts. It also draws a potentially more ‘longe durée’ view of Serbian nationalism and its attitudes towards Muslims as noted by Cohen.[6]

The Chetniks were noted by the Partizan regime for their ideological incompatibility, conflict with the Partizans and crimes committed against other ethnic groups. In addition to the inescapable fact of Chetnik’s collaboration with various fascists of German, Italian and even Croatian origin.

THE ERADICATION OF CHETNIKS

Draza Mihailovic and other Chetnik leaders were sentenced to death by the new regime, killing the Chetnik movement in Serbia and making sure the legacy of the Chetniks was given very little room to propagate by the regime and stamped out within Yugoslavia.

After the execution of Mihailovic and other Chetniks, historiography in Yugoslavia and specifically Serbian historians tended to ignore the Second World War period entirely. The topics of atrocities either committed by Chetniks against other ethnic groups or by paramilitaries comprised of Croats or Bosniaks against Serbs was considered a taboo and sensitive topic and avoided by historians, more so for reasons of preserving ethnic harmony than reprisal for censorship.[7]

During the Yugoslavia period, there were many reasons why the regimen clamped down on the Chetniks as mentioned above, the opposition of communism/market socialism to the right-wing monarchist views of the Chetniks and also the want, a belief in a united Yugoslavian people, and also a need to keep the Yugoslavian people united out of practical terms for the sake of the country’s stability, especially given that the death toll of the Second World War in Yugoslavia was considered to be much higher than more modern estimates.[8]

This proved mostly effective and the Chetnik legacy in Yugoslavia was muted throughout most of the Tito era. The new Socialist republic sought to bring the various peoples together under one state and set of institutions and saw a period of relative peace and prosperity in addition to relative liberalism compared to other communist states in Europe.

This did not prove to be sustainable once economic decline erupted during the 1970s and the regional inequality which saw Croatia noticeably more economically developed than Serbia[9] gave contemporary grievances a chance to marry the conflicts of the past, with the declining economy and regional inequalities within noted as having fuelled the Serbian sense of victimhood in these times.[10]

CHETNIKS ABROAD

The Chetnik movement being given little room to grow within Serbia left no other option but for the movement to spread elsewhere. Serbia, alongside the other nations of the Balkans, had been an emigrant people and thus were able to take their cultures and identities abroad to locations such as North America and Australia where a separate Serbian and Chetnik identity could flourish sans the socialist crackdown. Even the interwar Yugoslav (Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) sought to engage with the diaspora to maintain a ‘Yugoslav’ identity that replaced other national ones, recognising the potential threat of overseas contacts and returning emigrants abroad could pose to Yugoslav unity.[11]

Not much research has been conducted into what extent Tito’s government continued this policy, if at all, but several factors led to the Chetnik movement being able to continue abroad.

One key factor is the figure of Momcilo Dujic who was a Serbian priest and Chetnik commander born in the Dalmatian region of Croatia. Dujic was always considered to be very committed to the Chetnik cause and the Serbian Orthodox Church (which stands as a strong institution of Serbian identity and nationhood) which made him a key figure in the Chetniks.

Dujic’s role in the war is notable due to his relations with the Partisans and Fascists. Dujic led bands of Chetniks in the Knin region of Croatia and was notably one of the first Chetnik warlords to come into conflict with the Partizans,[12] as well as someone who took initiative to make contact with the Italian fascists for strategic purposes against the Partizans, which was seen as a grave betrayal by the Partizans who he had initially been working with.

After the Partizan victory, Momcilo had managed to avoid the fate of so many other Chetnik commanders like Mihailovic and had been able to flee to the United States. In the United States, he had already found a contingent of Serbs living in the United States and Americans of Serbian descent who had founded Orthodox Churches and heritage associations where the legacy of the Chetniks could be celebrated by Serbian nationalists.

This includes a key organisation that Dujic was given a key role in called the Serbian National Defense Council which has been relatively untouched by academic literature bar one paper in an American Journal of Serbian Studies that has not been digitised and is inaccessible. The group however has been noted as having protested the trial of Mihailovic outside the Yugoslav consulate nearly 20 years after Mihailovic’s death, with photographic evidence only seemingly having been noted by websites operated by Serbian nationalist networks in the USA themselves.[13]

The Serbian National Defense Council also had associations in Canada and Australia, the latter of which had a substantial Yugoslav diaspora. Ultimately the diaspora in the United States has been the most studied one. The Serbian National Defence Council was also accompanied by a more extremist organisation called the Serbian Fatherland Liberation Movement which sought to continue the legacy of the Chetniks by violently targeting Yugoslav officials in the United States.

Members of these organisations had attempted to bomb Yugoslav consulates and assassinate Yugoslav officials in the United States.[14] Reflecting the declining state of Yugoslavia where tensions were slowly, but surely, culminating. The group of assassins can also be directly linked to violence that would then plague the Balkans directly with the group of assassins’ most infamous member, Nikola Kavaja, moving to Kosovo to form what was deemed a defence militia comprised of ethnic Serbs.

This trend was also noted in Australia and violent radicalism was culminating in both the Serb and Croatian communities in the country, with ethnic violence on worksites between groups of Serbs and Croats and Croatian nationalist destruction of a monument of Mihailovic on the grounds of a Serbian Orthodox Church being linked to Croatian nationalists who escalated to more targeted and extreme violence.[15]

One of the more notable acts of Serbian nationalist diaspora violence was an attempt to kill Croatian Ustashe leader Ante Pavelic who was living as an exile in Argentina. Several émigré Chetniks had forged a plan to track him down and kill him and eventually a Serbian Chetnik émigré by the name of Blagoje Jovoic who was a member of an Argentinian organisation named after Mihailovic succeded. Although Pavelic survived, the sustained gunshot wound led to complications which eventually led to his death. [16]

DIASPORA ENGAGEMENT IN VIOLENT CONFLICT

The historiography of the connections to the diaspora in English is comparatively lighter with surprisingly less attention being paid to the role of these diaspora groups by either scholars in the United States or Australia, while literature on this topic is not entirely absent, further ongoing research may shed light on the wider international reach of the Yugoslavia conflicts.

It should also be noted that some scholars have concluded a stark contrast between the high diaspora engagement of the Croatian government[17] compared to the Serbian government of Slobodan Milosevic, who seemed wary of Serbs living abroad in spite of figures like Seselj making contact.[18]

Another point to note is also that the Serb and Yugoslav diaspora were not entirely nationalistic. One example noted by Paul Hockenos is that of Serbian-American businessman Milan Panic who attempted to broker a deal with Slobodan Milosevic to stop the war. Hockenos however notes that Panic’s lack of nationalism was out of character for Yugoslav emigres and speculates on his motives for dealing with Milosevic and the Serb lobby.[19]

CHETNIKS IN THE 90s

The conflicts that were emerging amongst the Serb and Croatian diasporas were also being felt at home as well. Increasing nationalism was taking root and being expressed by Serbs, Croats and other groups. This led to an increased interest in the Chetniks from both nationalist prominent figures and also at the base level.

The Serbian dissident intellectual Vojislav Seselj had finished an 8-year prison sentence for his beliefs and decided to travel to the United States to meet Momcilo Dujic. This meeting would have a key significance in Seselj’s life as a warlord in 1990s Yugoslavia with the meeting having been recorded by war crimes prosecutors.[20]

Dujic at the time was the head of an organisation called the ‘Chetnik Movement of the Free World’ and had met Seselj on the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo where he granted him the symbolic title of ‘Vojvoda’, translated as ‘Duke’ or ‘Warlord’, referring to a Chetnik commander. This meeting not only gave Seselj a renewed sense of purpose but also had many symbolic elements. The commemoration of the most symbolically important battle in Serbian history which has been noted as perhaps the key myth of Serbian identity by Anthony D Smith[21] and the passing of the baton from one generation of Chetniks to the next adds a quasi-religious quality to this meeting and shows a direct connection between the warlords of the 1940s and the 1990s.

Seselj was of course linked to the Serbian ‘White Eagles’ paramilitary group after receiving his quasi-christening from Dujic, along with other Serbian warlords of the time who were linked or wished to link themselves to the Chetniks of the Second World War. Radovan Karadzic was the son of a Chetnik fighter implicated in the massacre of Bosniak civilians in the Second World War and Arkan who had worn a Chetnik-style uniform in his wedding to singer Ceca, which was a large media sensation in Serbia at the time.

This shows an interest in the revival of the Chetnik legacy by Serbian politicians and the Serbian intellectual class, who provided an intellectual justification for the racist discrimination and massacres to come in the 1990s.[22] This led to the formation of paramilitaries modelled directly on the Chetniks who were a potent symbol of Serbian paramilitary violence in the past and therefore this was seen to an extent as the continuation of a longer conflict.

This increase in nationalism was also reflected in the general population of Serbia and not just intellectuals or politicians, with celebrations of the Chetniks becoming more common in public and via popular media. Gatherings of Serbian nationalists dressed as Chetnik warriors had been ongoing since the 1970s but in the midst of the collapsing Yugoslavia, the celebration of the Chetniks could be seen to have mass appeal.

The journalist Brian Hall who travelled through Yugoslavia in the 1990s reports the return of Chetnik symbols in public like the šajačka cap, associated with the Chetniks, that was not commonly worn before[23] and the re-invigoration of folk ballads sung by traditional bards playing the gusle about previous battles.[24] Suggesting that not only politicians and elite figures, but also strong ethnic ties and symbols that were held by common society in Serbia were also key in rising nationalism, aligning with Anthony D Smith’s theories on political nationalism[25] over Anderson’s more top-down perspective of nations as ‘imagined communities’.

THE RISE OF TURBOFOLK

Folk music in particular held a large sway during the era of Yugoslavia’s disintegration. Anuzlovic notes that the bardic gusle players were key transmitters of folk tales and ballads through the medium of their song to a rural and largely illiterate Serbian audience, passing tales down from father to son and making high literature accessible.[26]

The interest in folk music continued into the 90s and combined somewhat with electronic music to create a new genre of music at the time called turbofolk, which often contained typical lyrical content of folk or pop music but also often contained nationalistic themes and celebration of the Chetniks, of both the 1940s and 1990s.

Turbofolk is also distinctly Serbian in sound, Croatian and Bosnian nationalist singers would produce songs with Western rock instrumentation and musical style or Islamic nasheeds in the case of Bosniak singers, these singers likewise gained notoriety and fame during and after the war such as Marko Perkovic aka ‘Thompson’ from Croatia.

The distinctly Serbian sound, often nationalistic lyrics and linked to organised crime made turbofolk the ideal soundtrack for the Serbian war against Bosnia and Croatia in spite of its low-brow status and lack of serious respect[27] Several artists such as Lepi Mica, Baja Mali Knindza and Rodoljub ‘Roki’ Vulovic whose lyrical content and music videos show glamorisation of the Chetnik legacy, many of these songs are still posted on social media by artists, record labels and Serbian nationalists so the music has contemporary interest post-war.

One example of these songs is Lepi Mica’s ‘Drazin barjak’ (Draza’s banner) which has an accompanying music video that shows the type of Serbian chetnik celebrations that had been taking place since the 1970s with both Chetnik veterans from the Second World War and younger people with Chetnik attire and banners along with armed fighters in the Yugoslav wars.

The chorus is translated as “If Draza’s banner were unfurled there would be no Albania and the Ravna Gora movement would spread to the three Serbian seas”.[28] This draws a link to the Chetniks and Mihailovic but also to contemporary Serbian irredentism, drawing a link between the past and the present and the often expansionist nature of Serbian nationalism throughout the decades.

Baja Mali Knindza is another turbofolk artist who also released nationalistic music in the 1990s and still regularly performs concerts in modern-day Serbia and Serbian areas of Bosnia, with songs explicitly about Chetnik figures such as Mihailovic like ‘Drazo’[29] He has been noted by other scholars for his music which displays a whole menagerie of Serbian nationalist symbols, myths and tropes such as anti-Croatian and anti-Bosniak racism, Orthodoxy, referral to perceived Serbian lands such as the River Drina[30] and the Chetniks.

Baja can be seen referring to the Chetniks in many videos and songs, such as ‘Cuti, cuti Ujko’ which is stylised as him exchanging insults with a Croatian combatant over the radio while referring to himself as a Chetnik, showing contemporary identification.[31]

Rodoljub Vulovic’s music takes several turns from the other two artists mentioned. It is stylistically not exactly turbofolk, is less racist towards Bosniaks and Croatians and has fewer overt Chetnik references. Vulovic even laments the nature of conflict and the situation he finds himself in, in songs such as ‘Kucni Prag’[32], something that was absent in turbofolk but found in anti-war Serbian rock music.[33]

Vulovic does have songs that are of interest though, one song, ‘Cujte Srbi Svijeta’ is an invitation to the Serbian diaspora overseas to ‘return’ to Serbia to fight for their country.[34] This displays how the diaspora links were felt by Serbs at the time and were not necessarily a one-sided affair or only one that was felt by more ‘elite’ nationalist groups.

Another song ‘Crni Bombardera’ refers to the Serbian military shooting down an American F-117 stealth bomber which was a prominent part of Serbian war propaganda.[35] The song contains an interesting reference to the United States as an “old friend from the previous war” referring to the Second World War.

CHETNIKS IN MEDIA

The Chetniks held somewhat of an esteemed position amongst Americans during the Second World War due to their image as anti-Nazi resisters but also as anti-Communists which suited US geopolitical opposition to the USSR. The Chetniks were commemorated with the film Chetniks: The Fighting Guerrillas and commemoration of Operation Halyard where Draza Mihailovic led a rescue operation of American servicemen against the Nazis, which has been commemorated both in the USA and in Serbia.

Other mediums of media such as cinema have commemorated the resistance in countries such as France and Italy, but the Chetnik revival of the 1990s did not transfer into cinema, which has a more ‘high-brow’ and respectable reputation. Serbian cinema of the 1990s such as ‘Rane’ presents the criminal underworld of Serbia at the time as enticing, but ultimately destructive, for the young protagonists while the older family members, who are easily swept up in nationalist rhetoric are portrayed in a somewhat more comical light. Along with the highly grossing Lepa Gore, Lepo Selo shows Serbian and Bosniak perspectives and fits a theme of Serbian cinema being not straightforwardly jingoistic like turbofolk.[36]

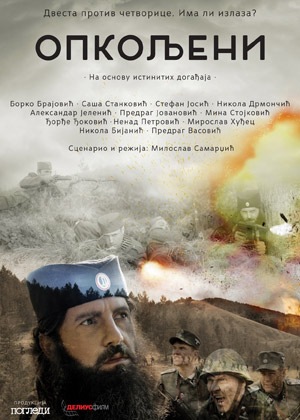

Cinema about the Chetniks has become more common in recent years and has usually brought controversy with it in countries neighbouring Serbia. The film ‘Surrounded’ was banned in Montenegrin cinemas following an outcry[37] and a similar controversy surrounding the film ‘Heroes of Halyard’ being shown at the Sarajevo Film Festival which caused an outcry from the public and the mayor of Sarajevo.[38]

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the legacy of the Chetniks in Serbia has many elements and can be seen as a multi-generational symbol of Serbian identity that has persisted via conflict with other nations and through mediums of folk music and legend, as well as mediums such as cinema to a lesser extent. Anthony D Smith’s theories on the need for nations to possess common symbols and reference points give the Chetniks a staying power in the Serbian imagination, especially when combined with Phillip Cohen’s arguments of there being a dark undercurrent in Serbian culture of identity of a need to dominate the Balkan region, which the Chetniks have played a vital part in Serbian attempts to do so.

Sources

Kajovesic, R (2022) Montenegrin Cinema Cancels Screening of Serbian Chetnik Movie Balkan Insight https://balkaninsight.com/2022/04/01/montenegrin-cinema-cancels-screening-of-serbian-chetnik-movie/

Khiss, P (23/11/1978) 5 Serbs accused of plot to bomb Chicago offices New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/1978/11/23/archives/5-serbs-accused-of-plot-to-bomb-chicago-offices-us-reports-tapes.html

Kurtic, A (2023) Bosnia Mayor Demands Resignations for Festival Promoting Film ‘Glorifying Chetniks’ Balkan Insight https://balkaninsight.com/2023/08/16/bosnia-mayor-demands-resignations-for-festival-promoting-film-glorifying-chetniks/

Nasa Srpksa Arhiva Lepi Mica – Drazin Barjak [TrueHD] Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FiHv2ZJDxuw&ab_channel=NSA-Na%C5%A1aSrpskaArhiva

Prosecutor for the trial against Vojislav Seslji Indictment International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia https://www.icty.org/x/cases/seselj/ind/en/ses-ii030115e.pdf

Rodoljub Roki Vulovic Official Roki Vulovic – Crni Bombarderi Official Video Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=333OVHhpK5c&ab_channel=RodoljubRokiVulovi%C4%87Official

Rodoljub Roki Vulovic Official Roki Vulovic – Cujte Srbi Svijeta Official Video Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ye69NQ2FbSU&ab_channel=RodoljubRokiVulovi%C4%87Official

Rodoljub Roki Vulovic Official Roki Vulovic – Kucni Prag Official Video Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jKyWihLG2-8&ab_channel=RodoljubRokiVulovi%C4%87Official

Superton Official Baja Mali Knindza – Cuti cuti Ujo (Official Video) Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNoy6FHHAU0&ab_channel=SupertonOfficial

Superton Official Baja Mali Knindza – Drazo (Official Video) Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTeReEyCNoM&ab_channel=SupertonOfficial

Secondary

Anzulovic, B. (1999). Heavenly Serbia: From Myth to Genocide. NYU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg56x

Bideleux and Jefferies (2007) A history of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change Second Edition Routledge

Brunnbauer, U (2012) Emigration Policies and Nation-building in Interwar Yugoslavia European History Quarterly 42(4) 602–627 sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0265691412458399

CARMICHAEL, C. (2013). Watch on the Drina: Genocide, War and Nationalist Ideology. History, 98(4 (332)), 592–605. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24429509

Carter, S. (2005). The Geopolitics of Diaspora. Area, 37(1), 54–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20004429

COHEN, P. J. (1997). THE IDEOLOGY AND HISTORICAL CONTINUITY OF SERBIA’S ANTI-ISLAMIC POLICY. Islamic Studies, 36(2/3), 361–382. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23076201

Cohen, P. J. (1996). The Complicity of Serbian Intellectuals in Genocide in the 1990s. In T. Cushman & S. G. Meštrović (Eds.), This Time We Knew: Western Responses to Genocide in Bosnia (pp. 39–64). NYU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfngn.5

Cooke, Philip E., and Ben Shepherd. European Resistance in the Second World War [internet Resource]. 2013. Web.

Garding, S. (2018). Weak by design? Diaspora engagement and institutional change in Croatia and Serbia. International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale de Science Politique, 39(3), 353–368. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26956739

Glenny, M (2017) The Balkans 1804-2012: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers Granta Publsihing

Hoare, Marko Attila, ‘The Great Serb Reaction, c. August–December 1941′, Genocide and Resistance in Hitler’s Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks, 1941–1943 (London, 2006; online edn, British Academy Scholarship Online, 31 Jan. 2012),

Kristic, I (2000) Serbia’s Wound Culture. Teenage Killers in Milošević’s Serbia: Srđan Dragojević’s Rane (The Celluloid Tinderbox, 2000) Central European Review

Nielsen CA. Serbian Historiography after 1991. Contemporary European History. 2020;29(1):90-103. doi:10.1017/S096077731900033X

Nielsen, C.A. (2020) Yugoslavia and Political assassination: The history and legacy of Tito’s campaign against the Emigres Bloomsbury p.208

Rebic, A (2013) Protest of the Serbian National Defense Council of America in front of the Yugoslav Consulate in Chicago 1964 GeneralMihailovich.com http://www.generalmihailovich.com/2013/01/protest-of-serbian-national-defense.html

Šentevska, I. (2014). “Turbo-Folk” as the Agent of Empire: On Discourses of Identity and Difference in Popular Culture. Journal of Narrative Theory, 44(3), 413–441. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24484792

Smith, A (1999) Myths and Memories of the Nation Oxford university Press

[1] Tasic, D (2020) Paramilitarism in the Balkans: Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Albania, 1917-1924, Oxford University Press

[2] Glenny, M (2017) The Balkans 1804-2012: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers Granta Publsihing p.486

[3] Ibid p.530-531

[4] Ibid p.489

[5] COHEN, P. J. (1997). THE IDEOLOGY AND HISTORICAL CONTINUITY OF SERBIA’S ANTI-ISLAMIC POLICY. Islamic Studies, 36(2/3), 361–382. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23076201

[6] Ibid

[7] Nielsen CA. Serbian Historiography after 1991. Contemporary European History. 2020;29(1):90-103. doi:10.1017/S096077731900033X p.17

[8] Bideleux and Jefferies (2007) A history of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change Second Edition Routledge

p.445

[9] Zizmond, E. (1992). The Collapse of the Yugoslav Economy. Soviet Studies, 44(1), 101–112. http://www.jstor.org/stable/152249 p.102 Table 1

[10] Yarashevich, V., & Karneyeva, Y. (2013). Economic reasons for the break-up of Yugoslavia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 46(2), 263–273. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48609746 p.270-271

[11] Brunnbauer, U (2012) Emigration Policies and Nation-building in Interwar Yugoslavia European History Quarterly 42(4) 602–627 sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0265691412458399 p.610

[12] Hoare, Marko Attila, ‘The Great Serb Reaction, c. August–December 1941′, Genocide and Resistance in Hitler’s Bosnia: The Partisans and the Chetniks, 1941–1943 (London, 2006; online edn, British Academy Scholarship Online, 31 Jan. 2012), https://doi.org/10.5871/bacad/9780197263808.003.0003

[13] Rebic, A (2013) Protest of the Serbian National Defense Council of America in front of the Yugoslav Consulate in Chicago 1964 GeneralMihailovich.com http://www.generalmihailovich.com/2013/01/protest-of-serbian-national-defense.html

[14] Khiss, P (23/11/1978) 5 Serbs accused of plot to bomb Chicago offices New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/1978/11/23/archives/5-serbs-accused-of-plot-to-bomb-chicago-offices-us-reports-tapes.html

[15] Incidents with connotations of violence within the Yugoslav community 1963-1972 The Act, Melbourne https://www.newspapers.com/image/122093880/?clipping_id=70288857&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjEyMjA5Mzg4MCwiaWF0IjoxNzAyNzgzMTkxLCJleHAiOjE3MDI4Njk1OTF9.tTW_XpG4f17mduLkDaWI7kKRIQqM35bY8mKkALkEGDk

[16] Nielsen, C.A. (2020) Yugoslavia and Political assassination: The history and legacy of Tito’s campaign against the Emigres Bloomsbury p.208

[17] Carter, S. (2005). The Geopolitics of Diaspora. Area, 37(1), 54–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20004429 p.60

[18] Garding, S. (2018). Weak by design? Diaspora engagement and institutional change in Croatia and Serbia. International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale de Science Politique, 39(3), 353–368. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26956739 p.362

[19] Hockenos, P. (2003). Homeland Calling: Exile Patriotism and the Balkan Wars. Cornell University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv2n7n6f p.157

[20] Prosecutor for the trial against Vojislav Seslji Indictment International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia https://www.icty.org/x/cases/seselj/ind/en/ses-ii030115e.pdf

[21] Smith, A (1999) Myths and Memories of the Nation Oxford university Press. P.155

[22] Cohen, P. J. (1996). The Complicity of Serbian Intellectuals in Genocide in the 1990s. In T. Cushman & S. G. Meštrović (Eds.), This Time We Knew: Western Responses to Genocide in Bosnia (pp. 39–64). NYU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfngn.5 p.56

[23] Hall, B (1994) The Impossible Country: A journey through the last days of Yugoslavia Minerva p.124-125

[24] Ibid p.127

[25] Smith, A (1999) Myths and Memories of the Nation Oxford university Press p.190-191

[26] Anzulovic, B. (1999). Heavenly Serbia: From Myth to Genocide. NYU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg56x p.11

[27] Šentevska, I. (2014). “Turbo-Folk” as the Agent of Empire: On Discourses of Identity and Difference in Popular Culture. Journal of Narrative Theory, 44(3), 413–441. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24484792 p.418-419

[28] Nasa Srpksa Arhiva Lepi Mica – Drazin Barjak [TrueHD] Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FiHv2ZJDxuw&ab_channel=NSA-Na%C5%A1aSrpskaArhiva

[29] Superton Official Baja Mali Knindza – Drazo (Official Video) Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTeReEyCNoM&ab_channel=SupertonOfficial

[30] CARMICHAEL, C. (2013). Watch on the Drina: Genocide, War and Nationalist Ideology. History, 98(4 (332)), 592–605. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24429509 p.601-602

[31] Superton Official Baja Mali Knindza – Cuti cuti Ujo (Official Video) Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNoy6FHHAU0&ab_channel=SupertonOfficial

[32] Rodoljub Roki Vulovic Official Roki Vulovic – Kucni Prag Official Video Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jKyWihLG2-8&ab_channel=RodoljubRokiVulovi%C4%87Official

[33] Šentevska, I. (2014). “Turbo-Folk” as the Agent of Empire: On Discourses of Identity and Difference in Popular Culture. Journal of Narrative Theory, 44(3), 413–441. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24484792 p.419

[34] Rodoljub Roki Vulovic Official Roki Vulovic – Cujte Srbi Svijeta Official Video Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ye69NQ2FbSU&ab_channel=RodoljubRokiVulovi%C4%87Official

[35] Rodoljub Roki Vulovic Official Roki Vulovic – Crni Bombarderi Official Video Youtube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=333OVHhpK5c&ab_channel=RodoljubRokiVulovi%C4%87Official

[36] Kristic, I (2000) Serbia’s Wound Culture. Teenage Killers in Milošević’s Serbia: Srđan Dragojević’s Rane (The Celluloid Tinderbox, 2000) Central European Review p.46-47

[37] Kajovesic, R (2022) Montenegrin Cinema Cancels Screening of Serbian Chetnik Movie Balkan Insight https://balkaninsight.com/2022/04/01/montenegrin-cinema-cancels-screening-of-serbian-chetnik-movie/

[38] Kurtic, A (2023) Bosnia Mayor Demands Resignations for Festival Promoting Film ‘Glorifying Chetniks’ Balkan Insight https://balkaninsight.com/2023/08/16/bosnia-mayor-demands-resignations-for-festival-promoting-film-glorifying-chetniks/

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.