Author: Nathan CJ Hood is a YouTuber and a graduate of the University of Edinburgh with a PhD in the History of Christianity. He is interested in mythology, fantasy and history, taking a special interest in the works of JRR Tolkien. He is also the founder of Excalibur Tours, which offers guided walks of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh focused on its Celtic and supernatural history. You can follow him on Twitter here, and his YouTube channel here.

Recently, I picked up a copy of Frank Miller’s 1986 miniseries The Dark Knight Returns. This was a seminal entry in superhero comics, and I think one of the reasons why it has been so influential is because it pushes the paradoxes underlying the Batman stories to their extremes. It forces the reader to confront the aspects of their neoliberal modern, individualistic worldview that we’d rather not explore, the things we bury deep down about ourselves and our society. It does so by imagining for us the consequences of a real-life Batman.

Can a man’s nature change? This is a central question throughout the miniseries. We see it first and foremost in the character of Bruce Wayne. We meet him ten years following his retirement from the role of Batman. The pale colouring in the panels reveals the absence of vitality in his life. He is an empty shell of a man, wandering the grey streets of Gotham. A flash of red greets us as Wayne is attacked by the Mutants, a gang of youths who do not rob for money or kill for gold. They delight in causing mayhem, in terrorising Gotham. They are the nihilist scourge. And in that encounter, something awakens in Wayne, a taste of his old life, of the power within him he is trying to suppress.

As Gotham spirals into anarchy, Wayne is drawn towards his old haunts. He returns to the Bat Cave, where once more we are met with the colour of Robin’s costume. He remembers the deaths of his parents. And within him, something burns bright, fierce and beautiful. Try as he might, the 55-year-old Wayne cannot stop it from bursting forth once more. So one night, the Batman returns. Across the city he makes his presence known, protecting innocents and thwarting muggers, rapists and murderers, his blue cape and yellow insignia a terror to the criminals who plague Gotham. And, for the first time in ten years, he feels right.

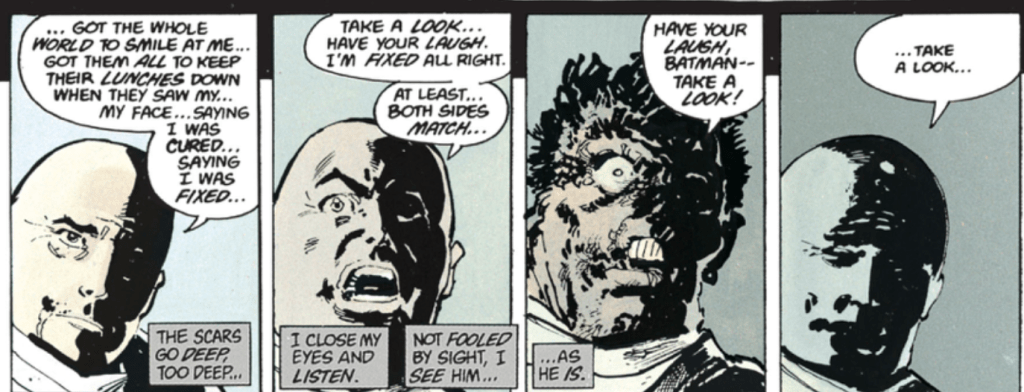

Mirroring Wayne’s transformation into Batman are the characters of Harvey Dent, also known as Two-Face, and the Joker. At the beginning of the story, they are both locked up in Arkham Asylum. Dent has been undergoing considerable psychological treatment under the supervision of Dr Bartholomew Wolper for his diagnosed psychosis. At the same time, Dr Herbert Williams has undertaken facial reconstruction on Dent’s face. The results are such that Dent is deemed fit to return to society. On release, he does appear a changed man. With his new, dashing looks, he delivers a press conference asking for forgiveness while pledging himself to a life of public service.

The same pattern is seen with the Joker. Since the disappearance of the Batman, he has been comatose. However, on hearing of the return of the Dark Knight, he begins to function once more. Dr Wolper works to psychologically help the Joker, believing he is helping his patient become sane. He goes further, arranging for the Joker to appear on a late-night talk show, both as part of his rehabilitation and to show that he is a ‘sensitive human being’ who has been the victim of Batman, drawn into the net of a psychosocial drama created by the caped crusader. More on that later.

Dr Wolper articulates a worldview that was prevalent during the twentieth century. Figures like Sigmund Freud established the discipline of psychology, studying and experimenting on the human mind. Freud and his followers believed that by curing the human mind, psychology could be used to heal broken individuals and create a healthy society. At the same time, there was a movement within the justice system away from a punitive model, which sentenced criminals according to the pain their crime merited, to a restorative form of treatment. The criminal was no longer seen as a ‘bad’ man who had done a ‘bad’ thing. Rather, he was a sick individual who needed to be treated for his illness. The prison system was there to remake the criminal into a fit member of society through medical practice. You can find out more about this by watching AA’s excellent series with Simon Roberts on Adam Curtis’s documentaries.

CS Lewis, Thomas Szasz and Paul Gottfried have highlighted the nefarious dimensions of this therapeutic state. No longer does a criminal get what he deserves: now he is kept imprisoned indefinitely until his ‘pathology’ is cured. The definition of pathology expands further and further as the expert class seeks more power over our lives and criminalises their political opponents. Examples include Wilhelm Reich and Theodore Adorno identifying the National Socialists as suffering from a psychosis caused by sexual repression, while the Soviet Union under Lenin and Stalin treated Christian dissidents as suffering from a disease that they attempted to treat through electrical experimentation on the brain. At the end of the process, if a man or woman can be remade by such psychological techniques, who knows what kind of creature will be produced? Ultimately, our relationship with the state has changed; we are treated like wards or pets owned and ruled by totalitarian specialists.

Despite top-of-the-range psychiatric treatment paid for by Bruce Wayne, Harvey Dent falls back into his persona as Two-Face. Even before his release Dent was worried that he was incapable of being cured, that he would relapse into a life of crime. Shortly after being let out of the Asylum, he rejoins his gang. He plans a major attack on Gotham’s twin towers. Landing the bombs on his target, he hacks the TV antenna. Appearing on the news, Dent threatens to blow them up and kill thousands unless he receives five million dollars. Batman intervenes and foils Dent’s plan. Seeing his scheme come to ruin, Two-Face throws himself from the tower, only to be saved by Batman. The two men talk. They are mirror reflections, unable to suppress their darker sides.

The same tale plays out with the Joker. Appearing on live TV, he goes on a killing spree. He slaughters the panel, including Dr Wolper, and the television audience. He then goes on the run, murdering more innocents at a theme park. It takes Batman pummelling the Joker into an inch of his life for the carnage to stop. The psychiatrists have failed. Dent, the Joker, they could not change. They could not be rehabilitated. This is why these men threaten the modern progressive worldview. The modern man wants to believe that a mixture of psychological treatment and social engineering can redeem anyone. For, they think, deep down everyone is good, and those who do bad things are the victims of social circumstances. Overturn the oppressive restraints and criminality will be cured. Underlying this set of beliefs is an overriding conviction that, through the powers of the managerial state and the instruments of science and technology, we can control everything, whether psychological, social or environmental.

But the truth is, nature cannot be bound. Human ingenuity is limited. No matter how hard we try, we cannot suppress two things. First, we cannot eradicate the shadow side of our personalities. We can try, but ultimately it will resurface once more, as it did for Batman, Two-Face and the Joker. Second, we cannot cure the shadow side of our societies. Monsters exist. They want to destroy our lives. They want to cause mayhem and kill us. We can only ignore their reality for so long. Eventually, they will burst forth once more if we do not maintain a vigilant defence. Even then, they may still break through. It is delusional to pretend otherwise. It is delusional to not act accordingly. Batman recognises this reality. That is why he is willing to go beyond the law and assault and torture criminals in order to save Gotham, though his inability or refusal to kill the Joker haunts him.

Nonetheless, Miller’s miniseries raises a potential counterpoint to this narrative. As mentioned earlier, the Mutants are a gang of youths. They commit random acts of violence. It transpires that they are led by a hulking brute, a powerful and quick savage who is in many ways the inspiration behind Bane in the Dark Knight Rises. Batman realises that the Mutants are bound together by the charisma of their leader. Defeat him, you bring down the gang. And so, after initially being crushed by the Mutant Leader, Batman returns to triumph over his foe. But the interesting thing is what happens next. Some of the Mutants for a new gang, the Sons of Batman, are dedicated to following their new champion. As anarchy escalates in Gotham Batman takes command of the gang and channels their violence. He directs them to use their fists to stop criminality in Gotham, eventually making it into the safest city in America. By the end of the miniseries, Bruce Wayne retires from active duty to train the Sons of Batman, having finally found purpose beyond the costume he once wore.

The Sons of Batman appear to go on a redemption arc. They start out as nihilistic thugs who bring Gotham to its knees. Though they continue to operate outside of the law, their aggressive, violent tendencies are redirected towards a noble end: the safety of the people of Gotham. Once agents of chaos, they are now the defenders of order. And it is interesting that they are made up of Gotham’s youth. They are a manifestation of a vital form of life, dangerous energy that cannot be contained by the structures of the old world. The bureaucrats, managers, TV talking heads and psychiatric experts have no answer to their fighting spirit. Instead, change comes in the form of a new leader.

As Thomas Carlyle argued, most of us are driven by a deep-seated desire which he called ‘hero-worship’. We have a natural tendency to admire, obey, and love great individuals, those who have the strength of character to impose their will upon the world. We follow their lead unto the ends of the earth. We would fight for these Great Men, we would die for them. In the modern world, we have this impulse satiated, albeit in a weak form, by sports stars, celebrities, and politicians. In the Dark Knight Returns, the Mutants want to follow something purer and more authentic than the media circus. So, they follow the Mutant Leader, a man committed to wreaking havoc in Gotham for its own sake. They imitate his appearance and actions. When Batman defeats their leader, they pledge their loyalty to the Dark Knight. They wear his symbol and follow his orders. They begin to hero-worship the Batman.

Batman, the perfect blend of hero and symbol, is the Great Man of Gotham. He draws its inhabitants into his orbit as he seeks to impose his vision upon the city. In the case of the Mutants, this has a positive effect. They are changed by his leadership and example. They are redeemed. They are the shadow utilised and directed towards a good end. But, as Dr Wolper pointed out, Batman’s primal form of power can awaken in others as darkness. Several mentally ill men end up killing innocents. The Joker awakes from a comatose state when he hears Batman has returned. The same kind of vitality Bruce Wayne found in his vigilantism is tapped into by a whole host of characters who enter into the costumed story. They find meaning in the battles conducted by the Caped Crusader, either on his side or against him. The quest that drives him and makes him a Great Man consumes those around him, whether for good or ill.

We might push further into the works of Carl Jung. He argued that National Socialism was not the product of psychosis or a pathology. Rather, it was the outward manifestation of a certain kind of agency, the spirit of Wotan. Neither a supernatural deity nor purely material reality, this was a kind of ferocious frenzied possession, a tornado within soul and society that tears down all without strong foundations. No individual created or controlled it. Rather, it was a social phenomenon, a way of being, that erupted in the hearts of Germans and exercised manipulation over their thoughts, feelings and actions. In esoteric circles, it might be called an egregore, an agent created by collective attitudes and consciousnesses that takes on a life of its own.

So too with Batman. Bruce Wayne is just as much caught up in the collective psychology of Batman as is the Joker, Harvey Dent, and the Mutants. It is an archetype, an egregore or spirit, that possesses the inhabitants of Gotham. Depending on who they are, they react to the symbol of Batman, grounded in but bigger than Bruce Wayne. It is a vortex which transforms men and women into beings with agency and morality. They can be redeemed, like the Sons of Batman, or they can become villains, like Dent and the Joker. But they do not stay neutral. They are forced to react to this new reality, to the mythic power of Batman. And through this interaction they find meaning. We might say they become who they truly are.

And what should strike us is that we too have a collective consciousness. There is a spirit that controls Britain, America, and the West. Within it there are roles and characters that we inhabit, parts we play without even realising it. So much of what we take for granted, what gives meaning to our lives, is bound up with this story. Many of us are dissatisfied with the narrative we inhabit. It feels broken and unnatural. It might be that we require a new spirit, a Batman of our age to come forth, as it will take a hero, a symbol bigger than the man who inhabits it, to change society for the better. This is the call in Miller’s Batman miniseries, a call which confronts each and every reader. And, through this article, it now confronts you too.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.