Author: Paul Heron. Paul is a Welsh writer based in Poland. He is active on X as @Paul_Heron_ and also runs an account dedicated to the work of J.G. Ballard, @QuotesOfJGB. You can find him on Substack here.

I

Robert Aickman, a brilliant English writer of “strange stories” (his own description) and a “saviour” of Britain’s canals (again his own description), was a man of singular opinions. Aickman looked back to the time before his year of birth (1914) as a lost age of elegance, freedom, luxury and ease—at least for the upper middle classes, to which his family had belonged. Accordingly, although he viewed the First World War as just and necessary, he also spoke of it as a grand tragedy, the great disaster of the modern age. That calamitous event had seen man ceasing, for the first time, “to be master of his own world”. For Aickman, the machine had been in the driving seat, rendering man a mere passenger of history—a foretaste of things to come. As we’ll see, in some of his stories Aickman explored the theme of technological progress as a threat, something antithetical to man’s autonomy and the limited happiness he has achieved.

As someone who took the paranormal, prophecy, astrology and other aspects of the occult seriously, Aickman could never get on with modernity’s rationalism and scientism. His uneasiness in the modern world is most evident in what he wrote on the subject of technology. His opinions on this matter were in line with his view of the tragic aspect of the First World War, and seem to have influenced all of his work. They can best be described as unusual:

“I believe that the key to the modern world lies in Samuel Butler’s suggestion that the machine is an evolutionary development, and that it is in the process of reducing man from homo sapiens to homo mechanicus; virtually to greenfly status. That machines have their own purposes and intelligences, though entirely different from the purposes and intelligences of men, and that they are rapidly taking over from men, seems to me plain, when once the concept is grasped and the totally different constitutions of machines from that of man is even fractionally allowed for.”

It’s clear this singular belief was central to Aickman’s mature thinking since he expounded on it in both volumes of his autobiography—the above quote comes from The River Runs Uphill, the second volume. Given the fatalism and eerie bleakness of this vision, the reader unfamiliar with Robert Aickman may well be wondering where the man found the motivation for the endeavours touched upon at this essay’s outset.

Firstly, I think there was another facet to this writer and conservationist’s relationship with technology—a certain fascination with what repelled him (and this essay will explore this facet in concert with the first). Secondly, Aickman’s highly romantic nature was key to the course he charted through life, leading him into, and through, endeavours that might seem pointless or hopeless to most. An observation made by his close friend Felice Pearson will be worth bearing in mind as we proceed: Aickman was, she said, suspicious of intellectuals, whom he found “desiccated”. Pearson did not put this down to her friend not being a university man—to spare his architect father an expense he could ill afford, Aickman had opted not to go to university—but instead attributed it to his temperament.

Those inclined toward a belief in nominative determinism may find special significance in the story of the Aickman family name. Here is Gary William Crawford in Robert Aickman: An Introduction:

“Aickman’s father [William] was of Scottish descent. “Aikman” is a common enough Scottish name, but the form “Aickman” arose from an error made in a legal document by an ancestor, who changed his name rather than the document. All Aickmans with a “c” are related to Robert.”

A surname with its origins in a curious blunder was, I think, very fitting for two men—William and Robert Aickman—who were oddballs and outsiders all their lives. In fact, the son described his father as “the oddest man I have ever known.” This can be taken as a statement with some weight: given that Robert moved in bohemian circles, especially in his younger years, he must have known more than a few odd men.

Robert Aickman’s disquieting vision of the coming hegemony of the machine was, by his own account, among his motivations for founding the organisation that did indeed—it’s no exaggeration to say—save the canals of Britain: the Inland Waterways Association. This he did in 1946 with fellow writer L.T.C. Rolt.

In the 1940s Aickman, with his wife Ray, ran the literary agency Richard Marsh Ltd, named after Robert’s grandfather, a successful novelist of whom the younger writer was very proud. Fittingly, Marsh’s most popular book had been the supernatural thriller The Beetle, which had outsold Dracula sixfold in 1897. Richard Marsh Ltd was Aickman’s only significant foray into the literary world at this point, the limited creative writings he’d produced (including a long philosophical tract entitled Panacea) having failed to find a publisher. L.T.C. Rolt, by contrast, was a successful author, the first printing of his debut book, Narrow Boat, having sold out in 1944. The book is an evocative account of a four-month journey on Britain’s then-crumbling canal network, a voyage from Oxfordshire to Cheshire and back undertaken by Rolt and his first wife Angela in 1939. Robert Aickman was among Narrow Boat’s first readers. In The River Runs Uphill, he writes he acquired a copy because, firstly, he’d always had an interest in the subject matter. And secondly, his star sign, Cancer, “has strong watery affinities”. Rolt’s book greatly impressed Aickman:

“Mr Rolt used this voyage as the foundation for sundry observations not only on the problem of the waterways but also on the plight of modern England, indeed of modern man; which the problem of the waterways appeared somewhat to symbolise.”

So taken was Aickman with Narrow Boat that he wrote to its author to suggest a meeting. Rolt responded with enthusiasm, inviting Aickman and his wife Ray to a meeting aboard Cressy, the Rolts’ boat, then moored at Tardebigge in Worcestershire. The two men found they had much in common: they both aspired toward the preservation and restoration of the waterways. Neither man cared much for where technological society seemed to be heading. While passionate about vintage cars, steam engines, canal boats and engineering in general, Rolt had serious qualms about mass production—he predicted it would eventually lead to the automatic procreation of machines by machines, bypassing man altogether.

Some months after the fruitful meeting, Aickman was aboard Cressy once again for his first canal voyage. As his biographer R.B. Russell notes, the technology of narrowboats, locks and canals was one he responded favourably to:

“Although Aickman disliked modern technology, and the canal systems were the original arteries of the Industrial Revolution, he was happy to embrace them because they operated on a human scale. In this instance, he believed, technology was subservient to the user, rather than the other way around.”

After some further months of contemplation, Aickman was decided and Rolt in accord. The I.W.A. was duly founded in February 1946 and initially was run out of the Aickmans’ flat on Gower Street, London. At the outset, there were four senior roles: Robert Aickman was chairman and Tom Rolt honorary secretary; associates of the pair filled the other positions. The I.W.A. was formed as a pressure group: through such measures as letter-writing campaigns, petitions, boat rallies and an annual festival, the Association succeeded in bringing the plight of the canals to wider public attention—and importantly, to parliamentary attention. Membership grew, and eventually, Aickman, Rolt and co.’s campaigning yielded tangible results, with money being found to restore some canals (decrepit locks were a particular problem). Aickman even managed to combine two of his passions by introducing a strong arts element into the first boat rally in 1950: there was Polish National Dancing, performances from various bands, the election of a Festival Queen and much else besides. Decades before Werner Herzog made Fitzcarraldo, Aickman gave the performing arts an aquatic twist. His first volume of autobiography, The Attempted Rescue, lays out the ideological dimension of the whole waterways endeavour as he saw it. Aickman sought to offer a visionary alternative to the grim mainstream. For him, the waterways project was “a counter-demonstration” to relentless technological and bureaucratic progress and the smaller, duller, less free life Aickman believed they brought. It was also ”a redoubt”, a refuge from a modern Britain growing more intolerable—Aickman felt—with each passing year. Russell observes that, for Aickman:

“..the saving of the waterways was just a step on the road to a better future for the whole country..”

Rolt, much more of a practical man than Aickman, didn’t care for the latter introducing performing arts into the I.W.A.’s boat rallies and festivals. Nor was he supportive of Aickman’s wider aims, which struck him as grandiose. Aickman, ever ambitious, was adamant every mile of the canal should be saved. Rolt argued such an approach spread limited resources too thin. Instead, efforts should be concentrated on commercially viable canals. Rolt’s concern was not only for the canal network but also for the waterways’ working families, whose livelihoods and way of life were threatened. Earning a living was not a straightforward matter for Rolt either: he was reliant on his writing for income, and struggled to find the time to both write and fulfil his I.W.A. commitments. Aickman had no such problems, having inherited a private income from his parents. I believe that a person’s worldview cannot but be shaped by the particular economic circumstances he or she has to contend with. How we earn a living (and whether we have to earn one at all) moulds how we see the world. For me, the contrasting examples of Rolt and Aickman demonstrate that quite well.

So strained was the situation that Rolt resigned as honorary secretary in 1950. Though Aickman tried to persuade him to stay on, his fellow co-founder no longer wanted a leadership role. He did want to remain an I.W.A. member. Sadly, relations between the two progressively deteriorated, and in 1951 the chairman took the step of expelling Rolt from the Association—an action that shows the more unpleasant side of Aickman’s character.

The rest of the I.W.A.’s story need not detain us too long. Suffice to say, Aickman worked tirelessly as chairman—producing almost all the Association’s literature, writing countless letters, attending dinners, giving speeches and much else besides—until 1964, when he stepped down from that role, feeling his work was done and he could hand the reins over to capable successors. Although commercial use of the waterways (so important to Tom Rolt) had dwindled, the waterways lifestyle—pleasure-boating on the canals—was firmly established, with more and more people taking it up every year. Restoration of the waterways likewise continued apace. If the I.W.A.’s activities were not a first step toward a transformation of the country, they arguably succeeded as the ”counter-demonstration” to technological modernity that Aickman had envisaged back in the Forties.

II

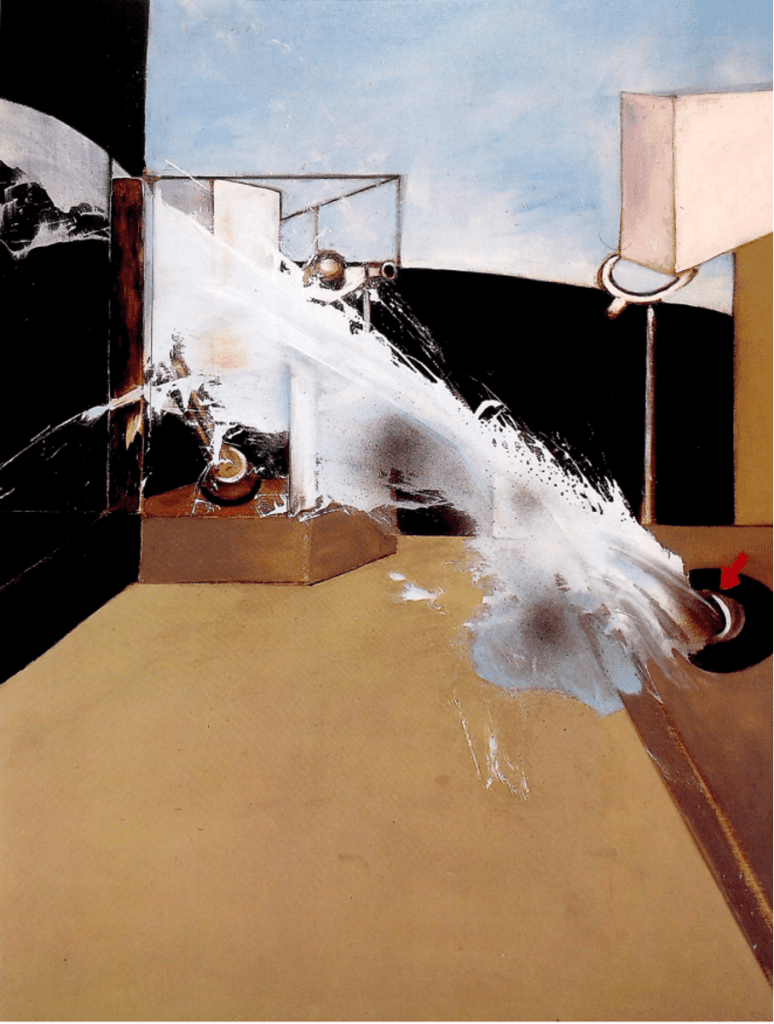

In 1988 Francis Bacon produced “Jet of Water”, “the best picture I’ve ever done”, as he boasted to friends. It was his second painting to bear the name. The first, similar but for me less successful, Bacon had produced in 1979. Both works present a scene devoid of human figures. As usual with Bacon the space is abstract, but it might be the inside of a factory. An open pipe is sending up a vigorous cascade, the titular jet of water. Michael Peppiatt describes the second painting evocatively in Anatomy of an Enigma, his Bacon biography:

“In the later, more rigorously simplified version, water gushes up from an open main into a space defined by two rudimentary and functionless machines. In its way, this was the grimmest painting Bacon ever produced. Mankind had been swept off the stage; so had the last shred of vegetation. All that remained was a kind of deserted factory, its futility highlighted by the vigour of escaping water. It was also Bacon at his funniest – one might say, his most Beckettian. For here was a vision far blacker and more insidious than man abandoned to his fate. Man had already been wiped off the scene, leaving behind only a post-industrial dumb show of his inadequacy.”

A bleak vision indeed, one strongly reminiscent of the darkest predictions of Robert Aickman and L.T.C. Rolt concerning the machine-dominated future. Francis Bacon was born in 1909, just a few years before the I.W.A.’s founders, and three years after Samuel Beckett. It’s tempting to conclude there was something local and generational in this vision of machinic absurdity. However, I don’t believe these were merely the fears of a single generation in the Anglosphere. Bacon’s Jet of Water finds another echo in the late work of a French writer born a couple of decades later, Jean Baudrillard (b. 1929). In Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?, the celebrated thinker contemplates humanity’s disappearance:

”For, if what is proper to human beings is not to realize all their possibilities, it is of the essence of the technical object to exhaust its possibilities and even to go quite some way beyond them, staking out in that way the definitive demarcation line between technical objects and human beings, to the point of deploying an infinite operational potential against human beings themselves and implying, sooner or later, their disappearance.”

Baudrillard’s vision of the (human) world ending with a whimper would not, it seems to me, have struck Robert Aickman as implausible. Indeed, it has strong affinities with themes the Englishman explored in his literary career, which began to take off (in a modest way) in the Fifties.

One story from that period merits this essay’s special attention. In “Your Tiny Hand Is Frozen” (1953), Aickman explores the threatening uncanniness of the technological world. The plot concerns a solitary man whose cheerless life comes to revolve entirely around a black rotary telephone. At the tale’s outset, Edmund St Jude has just moved into his fiancée’s rented London flat, sans his fiancée. His betrothed, Teddie, is a portrait painter, and canvases of children fill the apartment. Later we learn her absence is due to her being thousands of miles away, recovering from TB in a sanatorium in New Mexico. It is she who’s the owner of the telephone, thus when the device begins to mildly torment Edmund he’s loath to inconvenience her by having it disconnected. The trouble consists of unaccountable calls which disturb Edmund at unpredictable hours, interrupting both the translation work that occupies his days, and his solitary evenings and nights. Ignoring a call doesn’t work—the ringing being interminable, he has no choice but to answer. Each time the caller says nothing, and it’s never long before Edmund hears the click indicating they’ve hung up. At the close of one call, though, he hears a laugh and is convinced the sound came after the click. Throughout the story, Aickman toys with the boundary between the possible and the impossible where the telephone is concerned. In this way, he brings to the fore what might be called the uncanny aspect of the instrument.

The silent caller isn’t the only mystery served up by the troublesome black telephone. While ringing through his list of acquaintances hoping to find someone willing to visit him for Christmas dinner, Edmund is greeted by an unintelligible, gabbling voice that may not be a voice at all—he wonders if the noise might be an output from the telephone system itself. Here Aickman plays with another boundary, that between animate and inanimate—the telephone system does not seem to be as unambiguously on the inanimate side as one might expect.

It is in pursuit of Christmas companionship that Edmund makes the call that will turn him into even more of a phone addict than you or I. Although he dials the number of an ex-girlfriend, Queenie, it’s another woman who answers. This Nera (so she calls herself) proves to be an intriguing person, and she and Edmund hit it off. Nera promises to ring Edmund on Christmas Day. Curiously, her voice then gives way to a humming noise that gets progressively louder until Edmund, realising Nera has gone, hangs up.

Christmas Day comes and almost disappoints; at last, the evening is enlivened by Nera’s call. Yet at the end of it, Edmund can barely remember what they talked about, and he’s very surprised to note he’s been talking for over thirty minutes. Further calls follow, with Nera becoming more affectionate (she calls Edmund ”darling”) and Edmund increasingly smitten.

But no sooner has the lonely man found a measure of happiness than Teddie’s telephone begets another maddening mystery. Edmund begins to receive calls—a great many of them—from the Chromium Supergloss Corporation. As he fears missing a single one of Nera’s calls (he has tried phoning her on Queenie’s number but no one ever answers), he’s obliged to pick up on every occasion. Aickman writes:

”The incessant ‘wrong number’ calls tended to convert Edmund from a passive into an active servitor of the telephone.”

Naturally, this state of affairs is not the healthiest for Edmund. Like Marwood and Withnail in that cult film of the Eighties, he begins “to drift into the arena of the unwell.”

As is typical of Aickman’s strange stories, the ending both does and does not resolve things. There’s the sense we’ve been given a solution, of sorts, to a mystery—yet substantial questions remain, as the nature of that mystery was never made wholly clear in the first place. Nevertheless, “Your Tiny Hand Is Frozen” is, I suspect, yet more resonant today than it was when first published. Can’t we all, at least to some degree, recognise ourselves in phone-sick Edmund St Jude, forever awaiting the next call from the unseen Nera, that obscure object of his desire? I wonder if the phones we’re addicted to might be using us rather than the reverse. Arguably we’ve all taken on the role of “active servitor”.

III

Robert Aickman was always a great connoisseur of music—mainly classical and opera, with the Ring cycle a particular favourite. In The River Runs Uphill, he wrote he could no longer enjoy jazz after becoming aware that “the beat of the machine” ran through it. Like Marshall McLuhan, another highly original critic of modernity, Aickman had discovered a medium to be a message—a message he didn’t care for.

What’s more, although Aickman loved to travel he never learnt to drive, instead relying on licence-holders among his (typically female) friends—further confirmation he could never quite get on with machines.

Aickman was more a bohemian contrarian than a conservative, but he had respect for order, tradition and hierarchy. His suspicion of technology was tied up with an awareness that technological progress is inherently revolutionary, and as such, undermines traditional society. There were certainly plenty of examples of new technologies destroying traditional ways of life he could point to. For instance, the working boat families Tom Rolt tried, but ultimately failed, to help. And, more famously, there is the case of the Luddites. Pauperised by the coming of mass production and finally crushed—when they persisted in their machine-wrecking campaign—by the British Army, the artisan followers of mythical weaver Ned Ludd were one group for whom the Industrial Revolution brought only woe. Ernst Jünger noted this effect of technological progress on tradition in his extraordinary essay of 1930, “Total Mobilisation”:

”…hidden in every improvement of firearms-especially the increase in range-is an indirect assault on the conditions of absolute monarchy. Each such improvement promotes firing at individual targets, while the salvo incarnates the force of fixed command.”

We’ve been conditioned to think of the democratising impact of each new invention as an obviously good thing, but for Robert Aickman the benefits of the masses’ technological empowerment were dubious, to say the least. In his writings, he was fond of looking back to a more spiritual, more elegant, more hierarchical past, and he by no means restricted his historical interests to England. Pre-Revolutionary Russia held a particular fascination for Aickman. He gave expression to his romantic vision of that culture in “The Houses of the Russians”, a ghost story set largely in Finland, in pre-Revolutionary days a territory of the Tsar’s Empire. Though certainly eerie, the tale is more melancholic than terrifying and implicitly condemns Bolshevik atrocities.

The last strange story I’d like to briefly consider is “The Wine-Dark Sea”, another tale that comments on the vanishing of a world. Containing some of Aickman’s most hallucinatory prose, it is a surreal tour de force. As the title suggests, ancient Greek civilisation plays a role in this story. So does technology, though at the denouement only. The setting is a pair of islands in the Mediterranean or Aegean.

English tourist Grigg, holidaying on the much larger of the two islands, becomes intrigued by the other when he sees a beautiful sailboat head out from it to sea. By their reactions, the locals appear familiar with the boat and distinctly hostile toward whoever is piloting it. They refuse to discuss the vessel, or the other island, to which it’s supposedly impossible to travel. “There is no boat.” However, Grigg is too curious to be deterred. He steals a small boat and, apparently unnoticed, crosses over.

What he finds there is a partially ruined citadel of saffron-coloured stone. Clusters of flowers of all colours cover the structures of the fortress, and Grigg also finds the island home to lizards of a hue he cannot quite name. The creatures lay about a flight of marble steps he ascends into the main keep. Exploring that part of the citadel, Grigg finds traces of current occupancy. Sure enough, he soon meets the human, or human-like, residents of the fortress. After being startled by the sight of the elegant sailboat in the island’s small harbour (where previously only his own stolen boat had been moored), Grigg descends from the keep and meets the sailboat’s crew: three women of extraordinary grace and beauty. The unusual women claim to be sorceresses, and Grigg finds no reason to argue. They invite him to stay with them on the island. Having accepted the offer, Grigg soon comes to learn more about this remarkable place and its inhabitants. The island seems to preserve, through magic, a remnant of a very ancient world. This is Greece before the Greeks: a young, simple, savage world ruled by Chthonic forces, the world of the Oresteia. As the unhurried days go by, Grigg finds this pagan idyll to be a realm of both erotic delight and pitiless violence. When it comes to defending their island, the women have no qualms about murdering any trespassers not to their liking.

However, one such invader escapes detection until it’s too late. Before escaping, this hostile individual installs a machine of some kind in the citadel, and the device wreaks terrible destruction on the island (by what means we are not told). This machine is all the more unsettling for remaining unseen and undescribed.

What, I wonder, would Aickman make of Artificial Intelligence? I suspect he’d see in it a complete vindication of his view that machines “have their own purposes and intelligences”, purposes that are leading them to supplant human beings. It’s a process that we, mesmerised by our technology, are unwittingly aiding and abetting. This is one reason I believe Aickman’s strange stories are so relevant today: they are superb reminders that there is so much more to life than what the latest technologies are able to offer us. More subtly, they quietly draw attention to the strange and sinister aspects of our technological world.

Sources:

Aickman, Robert, The Attempted Rescue, Tartarus Press, 2013.

Aickman, Robert, The River Runs Uphill, J.M. Pearson, 1986.

Aickman, Robert, The Wine-Dark Sea, Faber & Faber, 2014.

Aickman, Robert, The Unsettled Dust, Faber & Faber, 2014.

Russell, R.B., Robert Aickman: An Attempted Biography, Tartarus Press, 2022.

William Crawford, Gary, Robert Aickman: An Introduction, Ash-Tree Press, 2011.

Rolt, L.T.C., Narrow Boat, The History Press, 2014.

Peppiatt, Michael, Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, Constable, 2008.

Baudrillard, Jean, Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?, Seagull Books, 2009.

Jünger, Ernst, Interwar Articles, Wewelsburg Archives, 2017.

Discover more from Decadent Serpent

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Robert Aickman’s life and works were completely unknown to me before reading this text. Everything which was mentioned in the text brings to me the works of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy). He was a Polish philosopher, playwright and painter. Witkacy was born in 1855 and he commited suicide in 1939. He was afraid of the Soviets and technology. I remember one of his plays where people have next to their houses special areas for clones. They look similar to humans who were living in the houses. The owners treat them badly. The clones are constantly hungry and they are cold. The clones are only vessels for internal organs which are being used to prolong the lives of the owners. It is difficult to find the demarkation line between human and non-human. The reader has to choose sides. You feel that clones are the victims but at the same time it is diffcult to say that the clones ought to kill the owners. I think that Aicman would like that play.

LikeLiked by 1 person